Campbell McGrath is the author of ten books of poetry, including Spring Comes to Chicago, Florida Poems, Seven Notebooks, and most recently XX: Poems for the Twentieth Century (Ecco Press, 2016), a Finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. He has received many of America’s major literary prizes for his work, including the Kingsley Tufts Award, a Continue Reading »

ON RECALIBRATING COLLABORATION

Emer Grant, Nora Khan & the Fellows of Recalibrated Institute at ArtCenter South Florida, Fall of 2017

BEST SHOW: CATHERINE INCE ON ARCADES PROJECT: CONTEMPORARY ART AND WALTER BENJAMIN AT THE JEWISH MUSEUM, NEW YORK, 2017

Workshop for Potential Design

Best Show: BRENDAN CORMIER on RAGNAR KJARTANSSON AT BARBICAN, LONDON, 2016

Workshop for Potential Design

Best Show: Sam Jacob on Thorne Miniature Rooms at the Art Institute of Chicago

Workshop for Potential Design

Sam Jacob is the principal of Sam Jacob Studio for Architecture and Design.

BEST SHOW: Vicky Richardson on GEGO. LINE as Object at The Henry Moore Foundation Leeds, 2014

Workshop for Potential Design

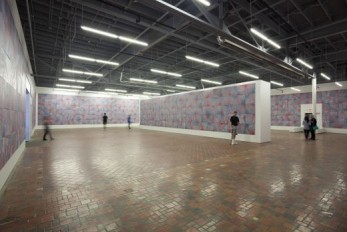

BEST SHOW: Alice Rawsthorn on 5 Weeks, 25 Days, 175 Hours by Maria Eichhorn at Chisenhale Gallery, London

Workshop for Potential Design

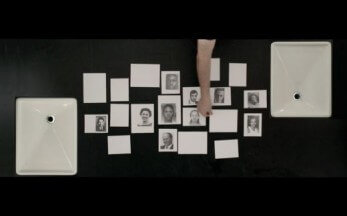

WFPD: Hello Alice, thank you for coming today. Alice Rawsthorn: My pleasure. WFPD: What’s the exhibition you will be talking about today? AR: The exhibition I’ve chosen is a show by the German artist Maria Eichhorn at Chisenhale Gallery in East London in Spring 2016. It was called 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours. Maria Continue Reading »

The Justification of Modernist Painting: A Review of Frank Stella: Experiment and Change

Nathan Timpano

Category Is—Family, Love, and Heartbreak: The House of Impossible Beauties by Joseph Cassara

Christopher Alonso

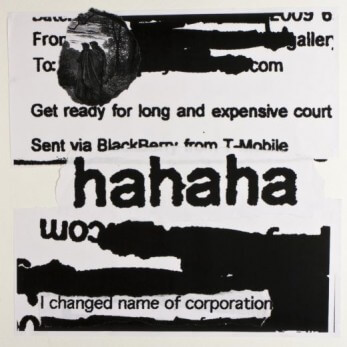

Memories and reminiscences of the late Miami artist from friends, lovers, and collaborators Compiled and edited by Bruce Posner INTRODUCTION – THE OBITUARY Charles Cornelius Recher was a native South Florida artist who created poetical works of short film, multimedia installation and performance, and other visual arts, as well as poetry and prose. Continue Reading »

#1: The Colony His bumper sticker says “Boycott any company that makes you press 1 for English.” The apartment complex is a dying vestige of Hollywood colonialism of faux stucco and golden orange paint. You turn down La Mirada Drive, circling around each cluster of condos. A woman wearing a hijab Continue Reading »

September 21, 2017 | 7:00 PM – 9:00 PM ArtCenter/South Florida – Downtown 1035 N Miami Ave, Miami, FL 33136 A panel discussion with Brandi Reddick, Jason Chandler, Germane Barnes, and Alexandra Cunningham Cameron moderated by Naomi Fisher, hosted by ArtCenter/South Florida. This panel discussion brings together members of Miami’s architecture and cultural affairs community Continue Reading »

August 22, 2017 | 7:00PM – 8:30PM The Lido Lounge @ The Standard Spa 40 Island Avenue Miami Beach, Florida 33139 Join The Standard and The Miami Rail for readings, advice, conversation, and cocktails, of course, with our new writers-in-residence, Alissa Nutting and Dean Dean Bakopoulos. The two lauded writers will be joined in conversation Continue Reading »

A New Day Has Come: A Review of Radical Hope: Letters of Love and Dissent in Dangerous Times

Natalie Lima

NSU Art Museum Fort Lauderdale February 12–June 18, 2017 One of the first photographs in Catherine Opie’s 700 Nimes Road depicts the iconic Andy Warhol screenprint of the actress Elizabeth Taylor. The supersaturated colors of the print dominate the left side of the photograph. An inscription, “to elizabeth with much love Andy Warhol,” along with Continue Reading »

AFTER CHARL LANDVREUGD, MOVT NR. 8: THE QUALITY OF 21 Dream of rooms, forgetting, how to see. As silent as paintings. Space, in which We build houses. For all of us to be. Camera of thought, as if remembering. Tomorrow’s colony naked and faint. His moon is behind me, changing. Come true. Behold our solid Continue Reading »

Between the lines of death: The Art of Death: Writing the Final Story by Edwidge Danticat

Dana De Greff

Ghazals Upon Returning to Hispañiola 1. It was diaspora or death: the oligarchs took everything, the Americans gawked. To think that a small place could fit so much hate; so we left. Carter helped, and for twenty years of Sunday’s the east river was tinfoil our mothers tried to smooth out, the towers on Broadway Continue Reading »

FLORIDA I look out my window to the sea. For fifteen years I’ve wanted an ocean view, and now I finally have one. But on stormy days the white waves seem to crash too close to my window. Everyone agrees South Florida is sinking, the limestone below so porous not even a seawall can save Continue Reading »

Any valuable object, in order to appeal to our sense of beauty must conform to the requirements of beauty and expensiveness both. This cannon of expensiveness also affects our tastes in such a way as inextricably to blend the mark of expensiveness… with the beautiful features of the object and to subsume the resultant effect Continue Reading »

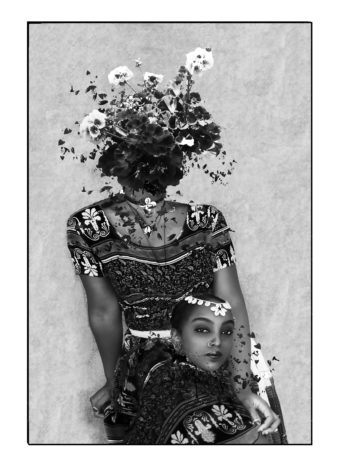

Creating a Platform for Exploration: Four Young Artists Explore Gender Fluidity and Identity

Veronica Mills

Thursday June 22, 2017 @ 7 pm The Lido Lounge @ The Standard Spa 40 Island Avenue Miami Beach, Florida 33139 The Standard & The Miami Rail are pleased to present our first Writer’s Retreat resident, Emily Raboteau. Join us June 22nd at 7PM for a reading, conversation, and cocktail reception with Emily and Alexandra Continue Reading »

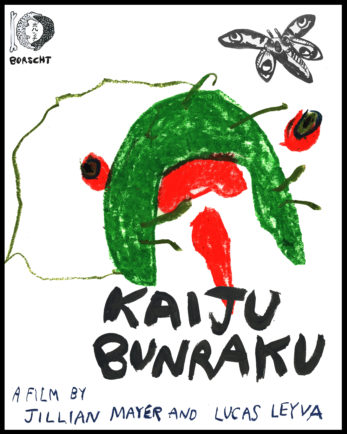

EXISTENTIALISM, TRANSCENDENCE, AND OBLIVION AT BORSCHT DIEZ: Three Short Film Reviews

Hans Morgenstern

Sarah Gerard’s second book is a blending of personal essay, deeply researched journalism, and sudden, gutting truths. In the title essay, Gerard writes of a green-cheeked conure she and her husband adopted: “She chewed everything… She sought out our wounds and pulled at them, then groomed open the flesh even wider. She had a taste Continue Reading »

Since first merging onto the Information Highway, I have harbored doubts as to whether scholarship could long survive the digital age. Google makes it so, so easy to skim the surface of a given subject, lighting here for this weighty quote, there for that purloined insight. Who could say whether a work is the product Continue Reading »

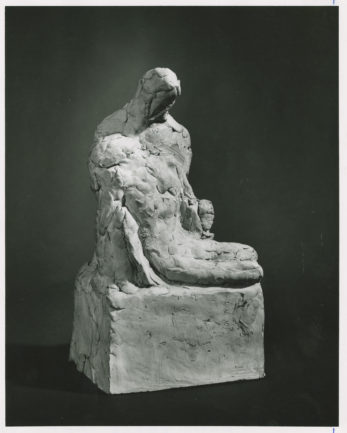

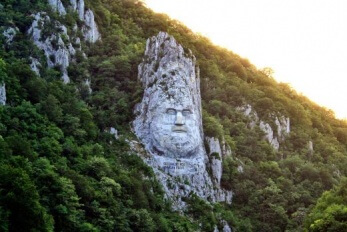

MĂIASTRA: A HISTORY OF ROMANIAN SCULPTURE IN TWENTY-FOUR PARTS Part IX: Charybdis

Dr. Igor Gyalakuthy

When I Grow Up is the backdrop to an exhibition of BUREAU SPECTACULAR’s work, entitled insideoutsidebetweenbeyond, currently on view at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. BUREAU SPECTACULAR is an operation of architectural affairs founded and led by Jimenez Lai since 2008. It is located in Los Angeles. BUREAU SPECTACULAR imagines other worlds and Continue Reading »

WE ARE A SHIP OF FOOLS: Magickal, Experimental, and Ridiculous Ideas to Save Miami from Sea Level Rise

Nathaniel Sandler

At the start of the 1954 season, a new amusement park opened up across the road from Aquafair. Aquafair’s owner, Mr. Rooks, has been trying week after week to sabotage the new park with the help of his right-hand man Lafe. A family emergency calls Rooks away, and Lafe is left to tend the park Continue Reading »

We show up, years beyond the animus, in the places that managed to keep them adrift or away from home— the pubs and hash-‘n’-eggs counters in other cities that answered our mothers’ where the hell is he before we learned and before where worked itself into why. Maybe we show up with them, indulging the Continue Reading »

PART VIII: EREBUS AND NYX If there was a man named Constantin Bălănescu, I never knew him. If this man occupied a not insignificant role in the diplomatic services of the Romania People’s Republic and went by the diminutive “Costel,” he and I never met. To me, to his family, and to his friends, the Continue Reading »

Thursday, November 10, 2016 at 7 PM / Free Entry The Little Haiti Cultural Complex 212 NE 59th Terrace Miami, FL 33137 Please RSVP to administrator@miamirail.org to confirm attendance! Ryan N. Dennis is the Public Art Director and Curator at Project Row Houses in Houston, Texas. Her work focuses on African-American contemporary art with a Continue Reading »

___________________________ 1. Peter Murray in Beatriz Colomina and Craig Buckley, Clip/Stamp/Fold: The Radical Architecture of Little Magazines (New York: Actar, 2011), 30. 2. Stefano Boeri in Colomina and Buckley, 49. 3. Gwen Allen, Artists’ Magazines: An Alternative Space for Art (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2011), 3. 4. Stephen Perkins, “Alternative Art Publishing: Artists’ Magazines (1960-1980),” Approaching Continue Reading »

Part A. The Set Up, A Pitch. The 2008 crash forced Contemporary Art (CA) institutions to restructure their financial dependencies and sources; a process that only exaggerated what had started after economic shifts in the 1970’s dried up public funding for the arts and recalibrated those models toward a dependency on corporate sponsorships. In some Continue Reading »

________________________________ 1. See for example the story of “BHAAAD – Boyle Heights Alliance Against Artwashing and Displacement,” in Los Angeles: http://observer.com/2016/07/one-la-hood-is-violently-fighting-gentrification-demanding-art-galleries-leave/ 2. Frederic Jameson, “The Aesthetics of Singularity,” in: New Left Review 92, March-April 2015, pp. 130-131 3. See: Max Kozloff, “American Painting During The Cold War,” Artforum Vol. 11, No. 9, May 1973 and: Continue Reading »

_____________________________________ 1. Marginal Ecologies: accidental habitat; The unintended product of human activity and nature’s unflagging opportunism; a weedy cosmopolitan community in the wastelands and margins of the urban landscape from a central business district to the suburban/rural fringe. (From Kevin Michael Anderson, Marginal Nature: Urban Wastelands and the Geography of Nature, 2009) 2. Tsing, A. Continue Reading »

______________________ This essay was commissioned by the Miami Rail as part of Field Perspectives-a co-publishing initiative with Miami Rail, Temporary Art Review and Common Field for the 2016 Common Field Convening.

______________________________ 1. Rebecca Solnit and Susan Schwartzenberg, Hollow City: The Siege of San Francisco and the Crisis of American Urbanism (London: Verso Press, 2000), p. 138. 2. Madeleine Schwartz, “The Art of Gentrification,” Dissent (Winter 2014). https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/the-art-of-gentrification 3. Sharon Zukin, Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), Continue Reading »

1. Rhett Herman, “How fast is the Earth moving?” Scientific American. 2. Karen Barad, “Nature’s Queer Performativity,” KVINDER, KØN & FORSKNING NR. 1-2, 2012. 3. For a competent mythography of Castillo, see Goyanes’ “SONGS FEEL LIKE MUSCLE MEMORY, OR, I’M OFF SOCIAL MEDIA, HMU ON YOUTUBE: A Mythography of Domingo Castillo,” The Miami Rail, 2015. Continue Reading »

THE SITWELLS ORGANIZE A ROYAL POETRY BENEFIT FOR THE FREE FRENCH WITH: EDMUND BLUNDEN, GORDON BOTTOMLEY, H.D., WALTER DE LA MARE, T.S. ELIOT, JOHN MASEFIELD, EDITH AND OSBERT SITWELL, WALTER TURNER, ARTHUR WALEY, LADY WELLESLEY, AND VITA SACK-VILLE WEST (Aeolian Hall, April 14, 1943)

George Green

Wednesday, September 28, 2016 at 7 PM // Free Entry ArtCenter/South Florida – Downtown Miami 1035 N Miami Ave #300 Miami, FL 33136 Please join us for our 18th Visiting Writer lecture with Laura McLean-Ferris of the Swiss Institute at ArtCenter/South Florida’s Downtown Location. Laura McLean-Ferris is a writer and curator based in New York. She is Continue Reading »

Saturday, September 24, 2016 at 3 PM // Free Entry – RSVP Only Well of Ancient Mysteries 87 SW 11 Street Miami, FL 33130 Join artist and writer Franky Cruz as he guides us on a tour of the Miami Circle and the cradle of Miami civilization built by the Tequesta natives at least a millennia ago. Continue Reading »

Alan Gutierrez, UNTITLED (rain scene), 2016 Sunday September 11, 2016 at 1PM // Free Entry The talk is directly followed by a Fringe Projects walking tour of nearby sites downtown Miami Center for Architecture & Design Second Floor 100 NE 1st Ave, Miami, FL 33132 Please RSVP to administrator@miamirail.org Please join us for our third Continue Reading »

Thursday August 25, 2016 at 7PM / Free Entry Rec Room @ The Gale South Beach Hotel 1690 Collins Ave, Miami Beach, FL 33139 786-975-2555 Please RSVP to administrator@miamirail.org Join us for our second Block by Block event with Nathaniel Sandler, founder and director of Bookleggers Library and interim Managing Editor of The Miami Rail. Continue Reading »

Thursday July 28, 2016 at 7PM / Free Entry The Little Haiti Cultural Complex 212 NE 59th Terrace Miami, FL 33137 305-960-2969 Please RSVP to administrator@miamirail.org The Miami Rail is pleased to announce the launch of our Block by Block program. Block by Block invites Miami based writers, to engage specific communities and neighborhoods in Continue Reading »

Friday, June 24, 2016 at 7 PM / Free Entry ArtCenter/South Florida – Downtown Miami 1035 N Miami Ave #300 Miami, FL 33136 Please RSVP to administrator@miamirail.org The Miami Rail is pleased to announce our 19th Visiting Writer Rujeko Hockley. Rujeko Hockley is the Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art at the Brooklyn Museum. Her interests Continue Reading »

New Zealander artist Susan Te Kahurangi King’s debut exhibition in North America opens this summer at ICA Miami, curated by Tina Kukielski. Recently appointed to the executive directorship of ART21, an organization specializing in digital media about contemporary art, Kukielski met with Sara Roffino in her New York office to discuss her interest in King’s work, the challenges of curating an exhibition of work by a nonverbal artist, and the next steps for the organization she now leads.

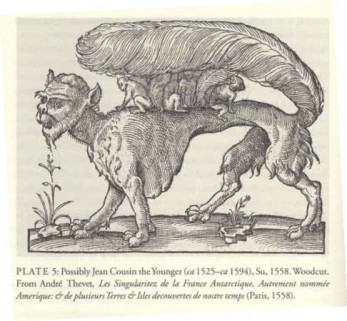

Some Irreverent and True Early Conceptions of Florida As Under-explained Reasons For Why This Part of the World is Consistently and Continually Absurd

Nathaniel Sandler

Palm Tree Like crackling icicles, your brittle sword-branches rattle in the small breezes of thick warm nights . . . —EMIL A. HARTE Maybe even our real names, in a way, are pseudonyms. In 1937, during her final attempt to circumnavigate the world at its equator, Amelia Earhart spent eight days in Miami to repair Continue Reading »

Friday, March 25, 2016 at 6:30PM / Free Entry Institute of Contemporary Art Miami 4040 NE 2nd Avenue, Miami, FL 33137 305-901-5272 Please RSVP to administrator@miamirail.org The Miami Rail is pleased to present Evan Moffitt, our 18th Visiting Writer to date. Moffitt is a New York-based writer and Assistant Editor at frieze. His work has Continue Reading »

Asleep in the sun

of your arms

then cold

when you’re gone.

NO MORE SAND: Thoughts Composed Discursively aboard the SuperFast Gambling Boat Somewhere between Miami and Bimini

Nick County

A JOURNEY BETWEEN THE BOSPHORUS AND THE SEA OF MARMARA: Impressions from the Istanbul Biennial

Ombretta Agro Andruff

Deep in the gated glens of Morningside, Felice Grodin built a temporary outpost of installations, conversations, and interactions.

A very cursory googling of “critiquing children’s art” generates a list of boorish sites such as I Am Better Than Your Kids and Art Critiquing the Life Out of Your Kids, such that could only be the work of dumb, desperate adults.

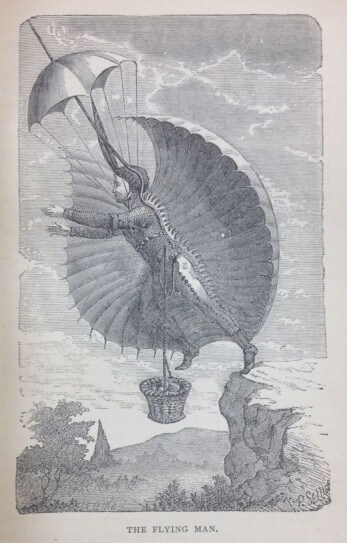

It seems flight is on Miami’s mind: there’s the history of flight in our summer issue, last night’s Curious Vault Collaboration detailed below, and Michael Namkung’s upcoming show Flying Towards the Ground at Locust Projects in August. Something in the air, perhaps?

“The uneducated use of acrylic…is a disaster,” said Charles Hollis Jones.

The Miami Rail is pleased to present Courtney Malick, our 15th Visiting Writer to date. Malick is a regular contributor to Artforum, San Francisco Arts Quarterly, and V Magazine, and is a founding member of Dis Magazine.

As we enter the twilight of Barack Obama’s presidency, the star of his icon is only beginning to rise. In office during the ascent of social media and the greatest explosion of images in history, Obama’s image, digitally encoded, will likely morph and proliferate over the coming years, before taking on the relatively stable orbit of history. Perhaps sensing this, the artist Rob Pruitt painted a portrait of Obama once a day, every day, since his inauguration.

I sit one night eating conch fritters at Beau’s Café on Wheels, a Bahamian food truck that stays, for the most part, on Plaza Street between Franklin and Charles Avenues in Coconut Grove. The dining area is a picnic table in Beau’s driveway. The menu variously includes items such as souse (a kind of Bahamian pork stew), conch salad, fried conch, and conch fritters, served with the ethereal “conch sauce,” the ingredients of which will not be revealed to me.

Awash in light, floated on wide pine flooring and white walls, cantilevered out to mega-foot sculpture galleries, and connected umbilically by stairs indoors and out, the art looks terrific. With all its big guns lined up—there’s Bellows! O’Keeffe! Hopper! Bourgeois!—the show could have sunk under the weight of its commitment to be a review of the Whitney’s history, but, billed as a gourmet tasting of more treats to come, it’s as frisky and promising as a pedigreed colt let out for its first full-length run.

“More goat than donkey.” This is how my father described B. P. Hasdeu, with an epithet he reserved for men whose intellects he admired and whose views he loathed. Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu was a Romanian writer and linguist, and a prominent figure in the Romanian intellectual community of the late nineteenth century. Hasdeu was the father of Protochronism, the delusional school of revisionist history that exaggerates the feats of the ancient Dacians, a Thracian tribe thought to be the ancestors of modern Romanians. [Note: Protochronism is a historical aggrandizement that was used by Communists to stir up nationalist pride, and is yet another Romanian cultural hemorrhoid, one we will be examining in greater detail in entries to come.] B. P. Hasdeu’s goatlike brilliance had the power to inspire and confound, and the impact of his work can be felt across Europe to this day. To Romanians, however, Hasdeu’s legacy will forever be coupled with that of his only daughter, Iulia.

Los Angeles-based artists Math Bass and Lauren Davis Fisher recently collaborated on the exhibition Math Bass: Off the Clock at MoMA PS1. The nature of the collaboration is interesting, not only because it counteracts the structure of a solo show, but also because the artists are uniquely connected through their simplified and pared down visual language and modes of operation, which incorporate raw materials, identifiable symbols, architectural forms, conditions of space, and shifting spatial perspectives. The artists—who live together in a space that is also shared by Fisher’s studio—discuss here their recent collaboration in the context of the personal and creative relationship it was built on, as well as the physical and theoretical overlaps in their respective practices.

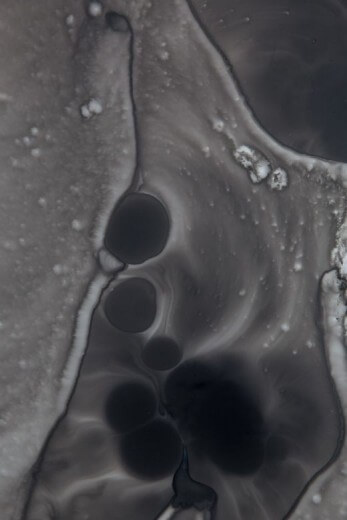

Minutes—or maybe even seconds—into viewing Ryan Sullivan’s paintings at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, the work induced a kind of reflexive mental search algorithm, bringing to mind a succession of names, images, and ideas: Jackson Pollock, Gutai, Robert Smithson, Andrei Tarkovsky, Star Trek, Edward Burtynsky, Paul Virilio, NASA, and global weather imaging.

With Order of Sorcery at Big Pictures Los Angeles, Aramis Gutierrez posits that you can be oppositional by being untimely; punk by being painterly. “Painting is potentially the most embarrassing medium because of its directness and its instinctive connection to skill and taste,” Gutierrez says. “It comes off as a bare-naked avatar of who we think we are, who we want to be, and what we think is going on.”

Intimate Material Systems, a solo show by Miami artist Leyden Rodriguez-Casanova, features a large-scale installation bordered by several recent wall and floor works that, as an ensemble, speak to a characteristic, painstaking inquiry about art, economics, and spirituality consistently present in the artist’s output.

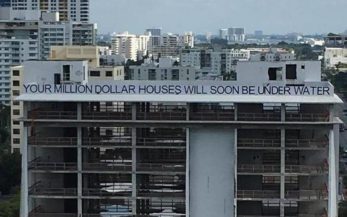

So recently culturally transformed, Miami will likely soon be transformed again, and more profoundly, by avenging nature. If the scientists’ best guesses are true, the rising sea levels ensured by the inexorable advance of global climate change will leave the epicenter of the pop-up hedonism of Art Basel an underwater ruin—sooner rather than later.

Neither art, nor the fitful, fickle affections of the global elite drawn by it, looks likely to staunch this rising tide. Indeed, inasmuch as some of the fortunes on parade each December have been made by dumping carbon into the atmosphere, the fairs play a bit part in the destruction of their own island habitat.

This is what Carol Munder does: she takes pictures, then she prints them.

She shoots black-and-white film with a Diana camera, a cheaply made, medium-format, plastic-lensed device first produced in the 1960s, sold to five-and-dimes by the gross, and often given away as novelties.

Diana cameras are the original fuzzbox of the photography world. They distort, they vignette, they are riddled with light leaks, and their ability to focus is largely theoretical.

The conjuring of monuments and memorial sculpture is the focus of New York- and Cairo-based artist Iman Issa’s series Heritage Studies, which comprises her recent solo exhibition at Pérez Art Museum Miami. Remaking is at the core of Issa’s practice, as is her critique of—or meditation on—cultural transmission, constructions of “the other” through art discourse and museological practices, and the role of art institutions in postcolonialism.

In a letter to his wife Lucy, John James Audubon described his first impression of Florida as “the poorest hole in Creation,” a disheartening observation in light of Audubon’s reputation as a spirited French-American of indefatigable passion.

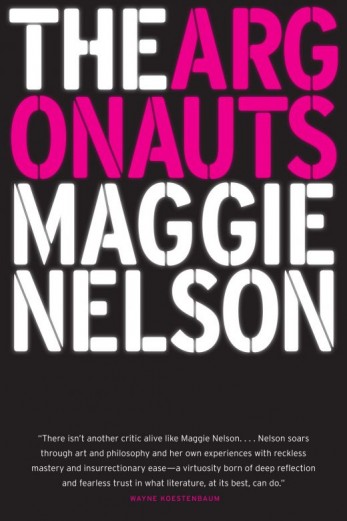

As I read The Argonauts, a list of questions lengthened in my mind. Who should I share this book with? Who, at least within my immediate family, would best relate to Maggie Nelson’s love, her tendencies toward delaminating names, and other habits of language? My aunt, not by blood, who made me mix-tapes of women rockers to listen to over and over again as a small child?

On March 26, 2015, Miami Beach celebrated its centennial, one hundred years of motley history capped off by the Hard Rock Rising Miami Beach Global Music Festival on 8th Street and Ocean Drive. Millions of dollars were spent on a centennial-themed park in the sand, complete with a Ferris wheel and a Hard Rock go-go dancer looming up above the entrance like a gargoyle Salome. Immediately inside, concertgoers passed through a Hard Rock gift shop and confronted the surreal lineup of Barry Gibb, Gloria Estefan, Andrea Bocelli, and Flo Rida.

Praise may not be the purpose—however we are gendered—but certain secretarial duties definitely have pride of place among the tasks of people who write poetry in 2015.

Satterwhite seems to be the ringleader of the world he makes, which is enriched by icons, objects from QVC, impermanence, form, maternal influences, and popular culture. His work investigates memory and desire, piecing conceptions of both together in a saturated and rendered, geometric plane of existence. Initially a painter who felt the limits of being still and later a video artist who found Adobe After Effects couldn’t perform in a way that matched his concepts, Satterwhite transitioned once again and taught himself Maya, a 3D animation software.

If you go to Andrew Yeomanson a.k.a.DJ Le Spam’s live/work studio in North Miami he will probably make you coffee. He’s got a restaurant-grade espresso machine in the kitchen and firmly believes that if your coffee beans were roasted more than two weeks ago, then they’re stale. The coffee machine is but one of Le Spam’s many prized possessions. Inundated by ceaseless tchotchkes and ephemera, every scrap of available surface area inside the City of Progress—as he calls his studio—is covered with vinyl records, cassette tapes, CDs, 8-tracks, and loads of audio equipment. He estimates there to be around fifteen thousand vinyl records all told, whether they be LPs, 45s, or 78s.

From the perspective of this Northeasterner and Miami novice, the city of Deco and Dolphins cuts a charmingly vexing silhouette. Like for many outsiders, my concept of Miami before I ever came to see it myself was a caricature: excess and tits lit by palm-frond sun shadows and neon hotel signs. And to be sure, those images are here. Caricature is, of course, always based on truths. And that’s one of the things about Miami I came to love—its un-self-conscious willingness to live up to its shit.

The room is walking

into a woman. It’s lying

to you again—hasn’t learned.

The room is walking into a woman

and he claims this time

he has evidence. A telephone

dangles from his white collar neck. Right.

That’s my cue.

Existing between abstraction, graphic art, Adobe CS, and the screen, Jesse Moretti’s work aims for a place where the supposedly discrete states––flatness/dimensionality and analogue/digital––merge. By creating a feedback loop between digital and material space in the studio, she collapses and unifies the pictorial plane. Born in Miami Beach, Moretti received her MFA from Cranbrook Academy of Art, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, in 2013. She has received residencies at MANA Contemporary ESKFF, Jersey City, and Pioneer Works Center for Arts and Innovation, Brooklyn.

Alternative Contemporaneity is a courageous attempt by director Babacar M’Bow, artist/curator Richard Haden,and educator Adrienne von Lattes to reclaim contemporary art from what M’Bow calls in his catalogue essay the “tiny, economic elite” who consider it (or, rather, its possession) solely as currency in the churning global market. For the MOCA team, contemporary art is nothing less than an exploration of what it means to be human amid the economic, social, and political systems that dehumanize.

Navigating the social and economic structures of the contemporary art world, critic and activist Ben Davis–the Miami Rail’s Visiting Writer for our upcoming Summer 2015 issue–will speak about his acclaimed book, 9.5 Theses on Art and Class, and other recent work.

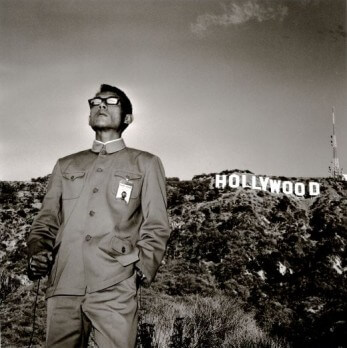

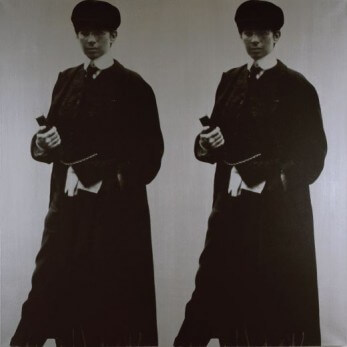

Tseng Kwong Chi was a prolific photographer who captured and participated in the downtown Manhattan art and club scene of the 1980s. He left behind an enduring archive of images of those well known artists, including Keith Haring, Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and the many lesser knowns who made up that particular moment in art-historical time. Though most known for this documentarian work, vastly more compelling is the oeuvre of surreal political portraitures of himself.

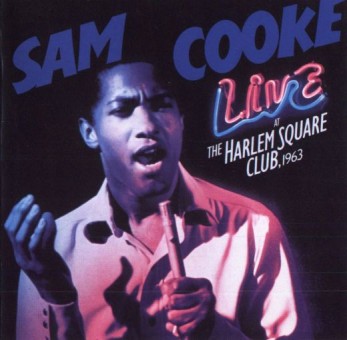

I saw a sound check version of Martine Syms’s Nite Life, which seems fitting for a work that investigates a raw club recording made in Miami in 1963 by Sam Cooke that wasn’t released until decades after his death. I heard a few comments after the actual performance that mostly dealt with the discussion about which category the work might fall under: is it an artwork? Is it merely a lecture? From where does its merit come? Increasingly, we see artists or cultural producers creating work that exists between boundaries.

Justine Ludwig and I spent a lot of time together during this year’s Dallas Arts Week. Previews, openings, after-parties; galas, auctions, dinners. But we never really had a chance to talk. So on Sunday, April 12, I guilted her into picking me up from my hotel at 1530 Main Street, and driving me to her place of work, Dallas Contemporary, located at 161 Glass Street. Not unlike the movie Speed, the following conversation only took place while we were in motion.

About his upcoming Takeover Tour of the Wolfsonian-FIU, the noise musician Rat Bastard quipped, “I’m going to come off like a guy talking to himself to the people attending this event.”

At Miami Dade College’s Museum of Art and Design—which is housed in the iconic Freedom Tower—artist Odalis Valdiviesco has a show of work titled Arrhythmic Suite. A series of about 70 paintings, photographs, and photocopies, they hang along a linear, horizontal line around the room, and on some of the 9 rectangular pillars in the middle of it.

A functional aesthetics is necessitated, in part, by climate. For hot climes, shorts and chancletas adorn the human form, and slits, slats, and holes dress the built ones.

Paddy Johnson, our Spring 2015 Visiting Writer, will be giving a public lecture at YoungArts on February 4th

Paintings by the artist Purvis Young depict swirled worlds of burning cities, tanks rolling to war, man-sized roaches attacking man-sized men. They’re not on clean canvases — they’re on the warped, chipped, and beautifully assembled wooden flotsam found on the streets of Miami.

One might think it would have been big news in museum circles when Merriam-Webster proclaimed its word of the year in 2014 to be “culture.”

“You can no longer find the original instruments to play Mozart on,” said Janet Eilber, artistic director of the Martha Graham Dance Company.

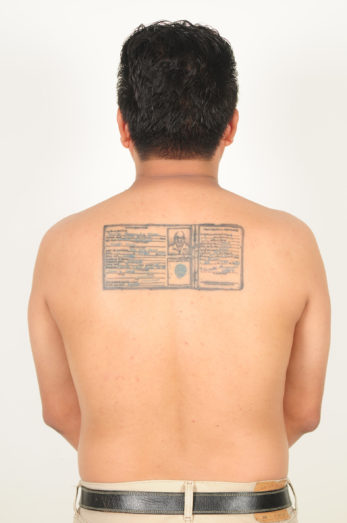

SONGS FEEL LIKE MUSCLE MEMORY, OR, I’M OFF SOCIAL MEDIA, HMU ON YOUTUBE: A Mythography of Domingo Castillo

Rob Goyanes

How do you write about an artist whose work is about everything but the work itself? This isn’t a fluffy profile of Domingo Castillo. It’s a fluffy profile of conceptualizations of Domingo Castillo.

The journey of the Stalin bronze, sculpted by the infamously outcast Dumitru Demu and torn down in 1962 in a period of De-Stalinization, is equally fascinating, though subject to rumor. The original has by now almost certainly been melted down.

Painting seems to have returned from the dead, again. The frequent pronouncement that painting is dead, followed by the declaration of its eventual resurrection, is an important, but often overlooked part of the modern (and postmodern) artistic tradition.

There are particular states of mind that can be described only as some potential elsewhere, but can’t quite be defined, and that are experienced by creation, particular stimuli, and collaboration. This wording might invite a transcendent, spiritual, or otherwise elevated connotation.

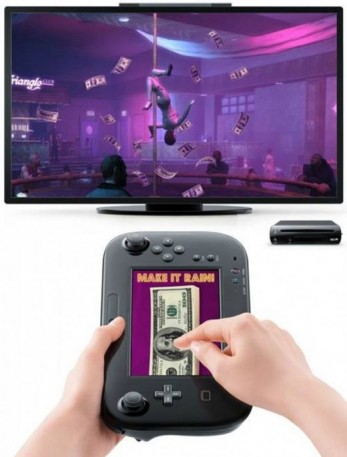

Miami artist Nicolas Lobo is known for giving form to the invisible forces that surround our everyday. Interested in object-oriented thought, his production is both intellectual and process-driven, and his works have revealed interests in a diverse range of phenomena and materials—illegal and informal markets, go-go dancers, and civic infrastructure; concrete, terrazzo, and napalm; and cough syrup, soda, and perfume. For The Leisure Pit, on view at Pérez Art Museum Miami this spring, Lobo used a swimming pool as an outsize tool in an experimental, custom casting process to produce a series of sculptures made from concrete forms submerged underwater and cast inside the pool itself.

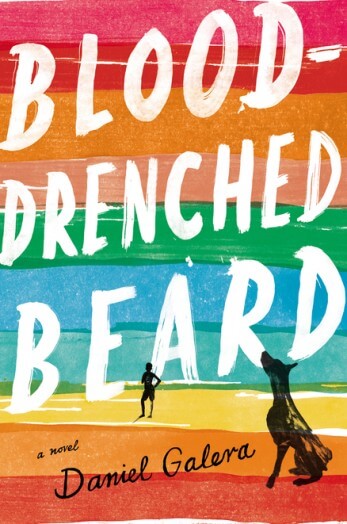

Having recently moved away from the beach and come into possession of a cat, I was a little too thrilled to read this novel about moving to the beach and coming into possession of a dog. Daniel Galera’s Blood-Drenched Beard is the story of young man who copes with a familial legacy of murder and suicide by moving to the Brazilian surf town of Garopaba.

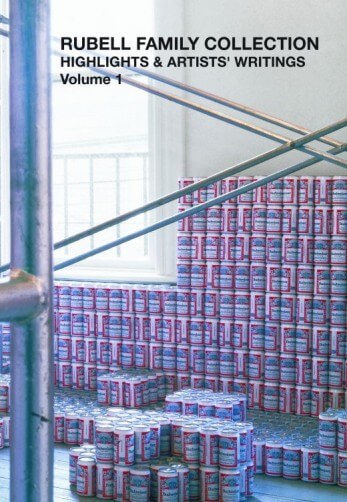

The Rubell Family Collection: Highlights and Artists’ Writings, Volume 1 was published to commemorate the Rubells’ fiftieth wedding anniversary and to mark the twentieth year that the collection has been open to the public. The book encapsulates a selection of 880 works from 250 artists represented in the collection. With more than 6,800 works by 832 artists to choose from, I do not envy that editing job.

One of my favorite artworks is Xu Bing’s 1st Class (2011), a rug made from half-a-million cigarettes. They stand leaning against each other on the floor to form a 40-by-15-foot “tiger pelt,” the stripes changing from tobacco-brown to filter-orange as you move around the piece. It is about decadence and death and industry and nature—from the history of the tobacco trade to big game—and it’s a perfect balance of all of these, humorous and serious at the same time.

The lava lamps mold the room. Pumping to the beat almost like a sentient central nervous system, they feed off the spirit of the place. Happiness, sadness, light, darkness, and beautiful hideousness grinding friendships into late nights and turn late nights toward the imaginary. The massive 8-bit Street Fighter paintings remind us it’s all a game. Put a quarter in. HADOUKEN.

Perhaps no one in Mexico City is more fully engaged with the praxis of merchandise display than the street vendors. Stands hawking nearly identical goods—plastic water guns, cigarette packs stamped with cautionary images of fetuses, striped socks packed in crackling cellophane, and the endless assemblages of Mexican candy (Duvalin, Pulparindo, Lucas Muecas)––are distinguished only by the particular dialogue among the objects. What draws you to this vendor and not to that vendor isn’t a certain stick of gum, it’s the gestalt.

It is a hallmark of grandly chaotic spectacles to be quietly defined by tight parameters, which, though seemingly antithetical to the outcome, actually contribute to the madness of it all. The best example of this might be rules that evolve in children’s playground games: this pole is home base, you can’t run past a building of this color, if you barely brush the chased party, he or she isn’t “it” anymore.

Wander through the galleries on the ground floor of Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM), and you can’t miss the imposing, six-foot-tall double painting of Barbra Streisand dressed as a male rabbinical student.

With Robert “Meatball” Lorie as your unofficial tour guide, it would be hard not to see Miami through a different lens.

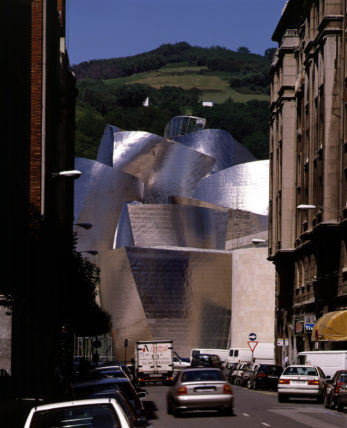

In April of this year a new stadium in Bordeaux, France, is set to be completed, designed by Herzog & de Meuron, the Swiss architectural firm behind, among many others, the Tate Modern in London (and its 2016 extension), the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, and Miami’s own Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM).

During Cecilia Vicuña’s recent busy visit to Santiago, Camila Marambio spoke with her at her childhood home. The relaunching of her 2006 LP “Kuntur Ko” by the independent New York record label Hueso Records brought her home to offer a series of timely performances and rituals composed in response to the destruction of glaciers in Chile.

“Don’t walk. Drive.” I can’t count the number of times I was given these instructions while visiting Miami, regardless of how close I was to my destination. I was offered this advice after having parked just a two-blocks’ walk away from Pérez Art Museum Miami to see a pop-up art project nearby.

Perhaps more than anything else, driving my rental car around the city defined my three-day stay in Miami. This marks a significant departure from my typical visit. Like most art tourists and professionals, I head to Miami Beach in December for the fairs, and if I travel around the city, it’s in a cab or art fair shuttle bus. I don’t rent a car, I don’t expect to get around quickly, and I don’t anticipate spending much time on Biscayne Boulevard. During those trips, I spend most of my days studying the floor plans of fairs and my nights blogging from a perch on my hotel bed.

Amanda + James

BFI

February 20, 2015

James Danner, founding director of New York–based Amanda + James, brought Francis Poulenc’s one-act opera for a soprano soloist, La Voix Humaine, to Miami over an unseasonably cool weekend in February. Before the show began, the audience, seated on the makeshift stage, or near to it, could hear downtown traffic and other nighttime noises just outside the large open doorway to BFI’s exhibition and performance space.

In the Blueshift Project’s brochure for Made in New York, a group show featuring eight New York artists and curated by Robert Dimin, an effort is made to express that the works on view are separate from the “noise” that results from the contemporary art fairs that swarm Miami each December. I visited the gallery on a quiet day soon after the show’s opening and was led through it by co-director Sofia Bastidas and manager Ana Clara Silva. Each had interesting insights to share about the overall concept of the grouping, which brings together many works that address the human and animal body and–—although made in New York—issues close to home in Miami.

At the opening of Michael Jon Gallery’s group show, someone kept turning off the lights. My wife thought this meant we should leave—but no, dimming the lights only makes for better viewing of Laddie John Dill’s celebrated untitled light work, which he first created in 1971 and has since been (laboriously) installed at the Venice Biennale, among other places. Showcased at the center of the gallery, mounds of sand and sediment house angular arrangements of glass panes that—when someone hits the lights—are softly illuminated from within by argon lighting just beneath the surface.

Art Lexïng debuted its new gallery space in Miami Ironside with a solo exhibition by Beijing-based artist Ye Hongxing. Selected in 2004 by the Asian Art Museum of California and Art Cologne as one of China’s twenty top rising artists, her work has been shown at the China Art Museum, Shanghai Museum of Contemporary Art, and Art Cologne, among others.

In connection with its current exhibition Myth and Machine: The First World War in Visual Culture, the Wolfsonian–Florida International University hosted artist Mary Reid Kelley for a screening of two of her WWI-inspired videos: Sadie, the Saddest Sadist (2009) and You Make Me Iliad (2010). Reid Kelley is well known for her forceful intellect, expressed in her extremely clever verse-making, biting and playful wordplay, ethereal screen presence, and her filmmaking itself, which entails meticulously researched production details such as drawn imagery, painstaking stop-motion lettering, and costume and set design digitally enhanced by her collaborator and husband Patrick Kelley.

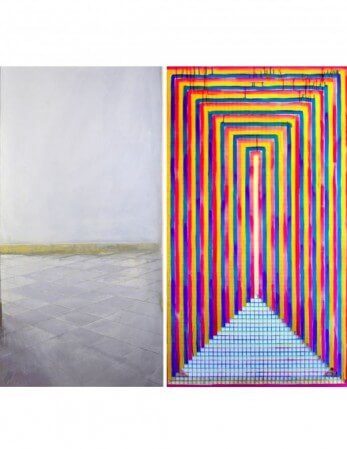

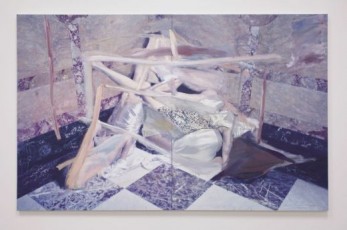

Organized by Rafael Domenech, Havana-born artist and curator, Binary // Binario features two young artists from Domenech’s alma mater, Havana’s Academia Nacional de Bellas Artes San Alejandro. Ernesto García Sánchez and José Manuel Mesías—both painters—approach their medium in divergent ways: Mesías draws largely on the unique visual quality of an aesthetic rooted in Cuba’s history and its cultural evolution, while Sánchez’s works fall in line with a long tradition of paintings that emphasize the medium itself, revealing the inner workings of the support via delicate cutaways in the canvas.

As the artist Nick Lobo told me over pisco sours at SuViche, Miami is a resort that grew, and grew some more, but it’s still a resort—a place where people come to get away from wherever and whatever they’re from, and whoever they were previously connected to, for a while or forever. The tourist hustle and the short con are as old as the sea and as new as that day’s sunlight. Visitors are welcomed, sized up, and fleeced in endlessly inventive ways that pepper the conversations of locals. Visitors who stay longer begin to welcome, size up, and fleece newcomers, in turn.

While Miami’s art scene is often faulted for lack of depth and conceptual rigor, there is enough intellectual energy here for a group of eight artists (spearheaded by Odalis Valdivieso and Lidija Slavkovic) to organize Fall Semester, a two-day rapid-fire conference where internationally recognized scholars, critics, and theorists came together to consider the city—especially this city, situated on the northern frontier of the global South.

Early on the morning of August 6, 2013, officers of the Miami Beach Police Department spotted REEFA tagging his name on a closed-down McDonald’s. He was adding his tag to a mix of signs and other graffiti that was already plastered on the walls. REEFA, standing at 5’6” and weighing roughly 150 pounds, ran from about six cops until he was cornered a few blocks away. After allegedly resisting arrest, he was knocked to the ground then stunned in the chest with a Taser by officer Jorge Mercado. As the officers celebrated, the suspect went into cardiac arrest. Once delivered to Mt. Sinai Hospital, as stated in the police report, Israel Hernandez “expired.” All he got up on the wall was the ‘R’ in REEFA.

When I tell new acquaintances that I direct Miami’s history museum, invariably they assume I’m making a joke. “Miami?” they gasp. “It doesn’t have any history!”

This fall, the PAMM curatorial staff and I took a museum patron trip to New Orleans for Prospect.3: Notes for Now. This is the third installment in a series of large international contemporary art surveys still labeled “biennial” by the organizers, though four years have passed since Prospect 2. The first Prospect, which opened in November 2008, was organized in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, in large part as an engine of economic and community development for the devastated city. This edition was organized by Franklin Sirmans, head of contemporary art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. In my opinion one of the most talented curators of his generation, he has built a resume heavy on exhibition and publication projects designed to redress the omissions of the Eurocentric Modernist art-historical canon, telling the stories and presenting the artistic achievements of significant yet lesser-known women artists and artists of color from around the world.

L’avenir (looking forward), the 2014 Montreal Biennale, arises from two perspectives that meet somewhere in the middle. L’avenir is French for what is to come. While that appears to be quite poetic, it could refer to anything between death and the pizza that you just ordered. Looking forward––well, you speak English. We have two conditions of the biennale: the expected object and state, and the expectation itself. Spread out over 14 venues, the biennale comprised 50 artists from 22 countries. Half the artists were from Canada; 16 were from Québec. Although it would be incorrect to reduce the art to a thematic checklist, it seemed that the majority of the pieces held a Janus-faced relationship to both the future and history. This relationship appeared structurally in many of the ongoing research-based projects on display. It also appeared in the content of many pieces explicitly dealing with history.

You say that your work is principally focused on the relationships of power that subjugate an individual within a determined context. Do you think that by positioning yourself as any individual you can obviate the fact that you are black? Did your work emerge from some kind of awareness regarding blackness? What are the origins of your work and what were the initial concerns that led you to art?

Lemon City, Lemon City becoming Little Haiti, Little Haiti becoming Little River. The Haitian-infused Miami neighborhoods present a state of flux, a city within a city encroached upon by new development interest while still establishing itself. A stunning photograph of a bush of fuchsia colored tropical flowers is offset by a road side at 62nd Street and NE 2nd Avenue in Miami, a site Adler Guerrier recognizes as a threshold between neighborhoods heavy with associations.

Fleeting Imaginaries is CIFO’s twelfth exhibition of artists funded through its granting program. The title describes the fluctuating, porous notion of a culturally specific sensibility, fitting for a show that brings together artists from seven different countries across Latin America, and yet the show is striking in its visual and conceptual cohesion. Seemingly chance coincidences of overlapping imagery and ideas occur repeatedly throughout the works in the show. Of course, the idea of a distinct cultural imagination is increasingly sublimated in a globally connected world characterized by diaspora and displacement. The problem with increasing interconnectedness is a reduction of linguistic and symbolic variation and hence a gradual homogenization of possible meaning in the face of creeping hegemonies.

Photographs and videos of the people who shaped Punk were recently on view at Ringling College’s Selby Gallery. Presented as joint exhibitions, Low Fidelity: Still Photographs by Bobby Grossman 1975-1983 recalled the style of a previous generation, and Underground Forces: Target Video 1977-1984 offered a time capsule of musicians and artists trying to establish themselves. Together, the exhibitions revealed how the movement continues to be affected by the way it’s represented.

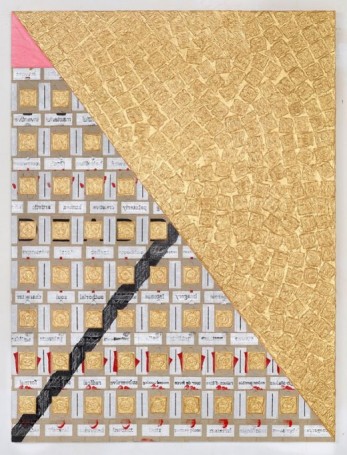

Curated by José Carlos Diaz for the Bass Museum of Art’s 50th anniversary, GOLD assesses the power, effect, and significance of gold through both literal and abstract approaches. The group show consists of 30 works from 24 multinational artists, all unified by the implementation of the precious metal in their pieces. Ranging from photography to sculpture to video, GOLD strengthens concepts of beautification, power, deception, perfection, ancestry, and divinity by encouraging viewers to question the capability of gold.

I just had show at Jumex with puppets, Permanent Revolution. It was my first production turning the museum into a theatre. The play intertwined art and politics: Diego Rivera invited Trotsky to Mexico and stay in his home, Frida Kahlo falls in love with Trotsky. There is an assassination plot with a Stalinist supporter, against Trotsky. It had romance, murder, art, politics, economics, intrigue, science fiction. Everything. My hope was to create something that wide audiences could follow. It’s going to tour Mexico; I’d like it to circulate in theaters.

Daniel Arsham and I grew up in Miami of the 1980s and 1990s. Our lives have intersected throughout the years, but we only became friends after working together on Snarkitecture’s Drift Pavilion for Design Miami/ in 2012. We recently met for breakfast one fall morning in New York to discuss our lives, new projects and his upcoming show at Locust Projects, Welcome to the Future.

It’s been three and a half decades since Julian Schnabel rocked the art world with an exhibition of paintings made on broken dinner plates. Since then, he’s never shied from reinvention, be it aesthetic, or personal. In one of his trademark expansions, he became known as a singular filmmaker, creating works like “Basquiat,” “Before Night Falls,” and “The Diving Bell and the Butterfly.” This fall, the Museum of Art | Fort Lauderdale presents yet another side of Schnabel—a painter connected in spirit to Francis Picabia and J.F. Willumsen. On the occasion of this exhibition, Café Dolly: Picabia, Schnabel, Willumsen, he spoke to the Miami Rail editor Hunter Braithwaite.

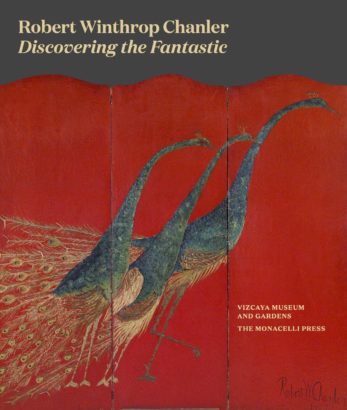

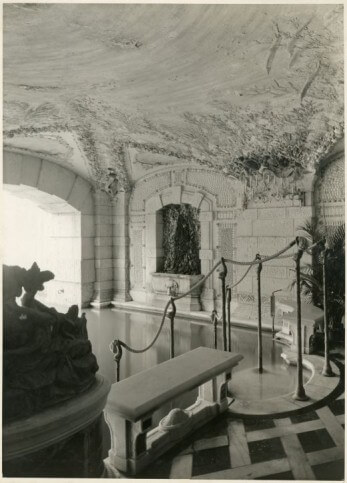

Ornate and extraneous, Robert Winthrop Chanler’s work at the Vizcaya Museum and Gardens can trace part of Miami’s history of wealth, patronage, and aesthetics that developed concurrently with its settlement. It also reminds visitors of South Florida’s almost immediate proclivity towards ostentation and decadence. Chanler was a descendant of some of New York’s most elite families (his mother was an Astor) and his artwork reflected the education he was able to attain, as well as the comfort within which he lived. He’s often characterized as an independent Modernist, someone who blended decorative, international style with fine art. The fantastical, exotic screens, murals, and architectural elements he created were distinct, and have remained unique from his peers. Despite the European avant-garde dominating the memory of the exhibition, Chanler had perhaps the largest American showing at the first Armory Show in 1913, which had particularly sought decorative artists.

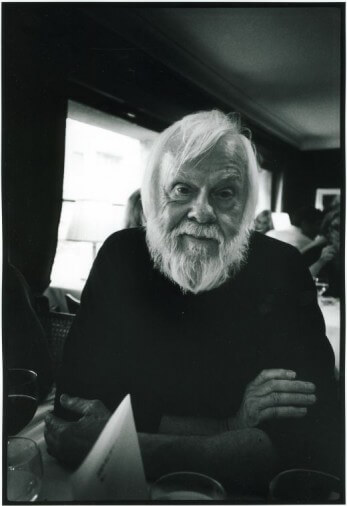

John Baldessari is one of the most influential artists of our time. Born in California during the summer of 1931, he has made art for the past six decades, ranging from his early practice as a painter to seminal conceptual artworks made using found photographs and texts. His projects include artist books, videos, films, and billboards. His artwork has been featured in more than 200 solo exhibitions and in over 1000 group exhibitions in the U.S. and Europe. In 2009 he received the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement, awarded by La Biennale di Venezia.

By weaving anthropology, sociology, and philosophy, the French thinker Bruno Latour has positioned himself at the frontier of Science Studies, a flexible and searching response to the Anthropocene. This September, he spoke to Miami Rail contributor Camila Marambio about dance, the climate, and the importance of working across disciplines. The conversation occurred on a bench at the Museo do Indio in Rio de Janeiro. The two were taking a break from the colloquium “The Thousand Names of Gaia: from the Anthropocene to the Age of the Earth” organized by Eduardo Viveiros de Castro and Latour himself.

Claudia La Rocco’s The Best Most Useless Dress is not poetry. That is, it’s not poetry exclusively, but an amalgam of writings, including criticism, handwritten notes, musings, and bits of conversation (also, images) with any combination of these at times appearing within a single piece. The result of all this would be disorienting were it not for recurring themes and phrases, and, perhaps more importantly, the earnestness with which she approaches each poem and the general sense that she has eschewed the desire to provide the reader with something polished and perfect. This meandering, this hesitation, this doubling back creates an intimacy with the reader that excuses some of the haphazardness of the work—no, not excuses—justifies.

Memory has been at the core of human existence from time immemorial. Our fleeting presence seems to be at the root of a pressing need to seize life through memory and remembrance—the only way, apparently, to defeat time.

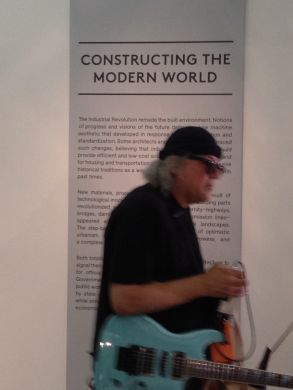

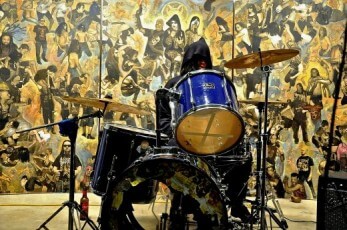

Echos Myron, co-curators Beatriz Monteavaro and Priyadarsini Ray’s exhibition of visual artists and musicians working shoulder to shoulder in South Florida, is a celebration of their scene. It’s a happily crowded show, but I didn’t notice any of the Wynwood-style art that would be a nod to hip-hop’s enormous influence on visual culture. Here, the aesthetic is punk and music is mostly shorthand for rock n’ roll.

Now in its third year, DWNTWN Art Days has grown exponentially with well over a hundred events taking place in downtown Miami on one weekend in September. Fringe Projects has acted as a curated public art exhibition during the weekend, offering a sense of artistic direction over the frantic schedule of activities. While past years have brought interesting projects, the efforts had been a tad scrappy and perhaps underwhelming (likely due to budget constraints). But this year, Fringe Projects has come into its own with a series of ambitious projects that have raised the curatorial stakes. Surprisingly, this is the first year that all of the selected commissions came from Miami artists, something that curator Amanda Sanfilippo mentions was a coincidence. That happy accident has given Fringe Projects a sense of vitality, as not only are many of these artists working outside of their element but are also creating incisive works that address rapidly changing city brimming with dualities.

Stepped up the curb and on beyond the doors of the SculptureCenter, which is housed in an expanded old trolley repair shop in Long Island City, Queens, and I saw an art show called Puddle, pothole, portal, which is thickly about childhood entertainment in the United S of America and, ergo, paradox, poop jokes, and since its art, a didactic treatment of the comic impulse as a socioeconomic response to the ever-changing/ever-malfunctioning of technologies, bodies, systems, selves—and if the latter sounds somewhat trite, it’s intended to, buddy, since everyone and all things do in fact just grow in discrete and sometimes secret ways until their ultimate undoing, a fact which is totally sad but sorta funny, it being both the spring and the void, etc.

The use in useless objects: they make the place feel populated.

People will go to heroic lengths to avoid introspection.

How do I look, by the light of the pale-faced moon?

Nicole Cherubini, a New York-based sculptor with a strong commitment to ceramics, recently opened 500, a solo exhibition at PAMM. Cherubini’s work incorporates a personalized symbolic formalism echoing her interest in utopian craft communities. She spoke with artist Christy Gast about this, as well as feminism, motherhood, and the role of the museum.

“Vanilla Ice was too expensive,” claims Jillian Mayer, through an early morning wry smirk. Apparently Bob Matt Van Winkle of ice-ice-baby-A1A-beach-front-avenue fame quoted his services at $10,000 to be involved in a film for the Borscht Film Festival and then jumped his rate to $50,000 as the deal started coming together. Cold blooded Ice. At the same time as this conversation was happening, Mayer the multimedia artist and filmmaker was serving up coffee and bagels with Publix-brand vanilla-flavored cream cheese at the Borsht Corp. offices. The vanilla-related synergy wasn’t purposeful and the cream cheese was fucking gross.

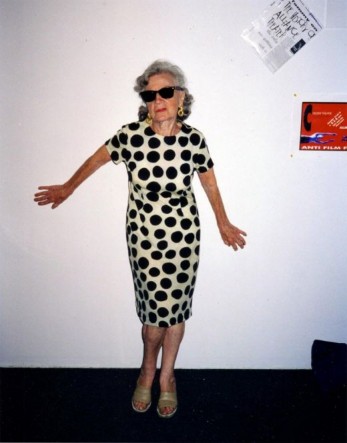

Agalma begins near the end. In the project gallery, a video called “Elysian Fields” features an elderly woman siting in a chair in the middle of a field, shoulders bare, flowers in her close-cropped hair, singing to Frank Sinatra. She is the artist’s grandmother: former showgirl, current Alzheimer’s patient. Nowadays, she’s only truly herself when she hears the songs of her youth. She emotes, she puckers her lips, she still has beautiful eyes. Sometimes the lyrics flood back. Sometimes she forgets them and you see frustration come across her face like a curtain. Through it all Casey’s camera stays close, shifts in and out of focus, heaving.

My grandfather raced on the beach course at Daytona in the late ’40s and early ’50s. Two miles up the beach sand and two miles back down A1A. He was never seriously injured but bore close witness to a spectator being struck by racers and all parties losing their lives. My father began racing in the early ’60s as pavement tracks took precedent over dirt. As speeds increased so did injuries, and he saw his fair share challenging to be one of America’s best. He learned early that broken bones were merely an inconvenience, rather than a deterrent from doing what he loved. At 12, he ran over his own leg at the now defunct Hialeah Speedway. A month later he cut his cast off with a hacksaw and decided not to return to the doctor.

Caribbean: Crossroads of the World, offering a 200-year survey of visual culture from the Caribbean Basin, results from more than a decade of devoted work by curator Elvis Fuentes. Taking as its point of departure the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804)— a pivotal moment that changed the Caribbean’s dynamics with Europe—in the history of the area, the exhibition rejects the reductionist and extended chronological vision of a place where the coexistence, persistence, and overlap of different historic eras is one of the most outstanding endogenous characteristic.

Held in the city’s dormant summer months since 2012, The Miami Performance International Festival offers artists from the States, Latin America, the Caribbean, and Europe a public platform far from Art Basel. Organized by artist and curator Charo Oquet the festival is unrefined compared to market-driven fairs, allowing artists to express challenging themes that emphasize the pressures of conformity and emotional states of being.

Much has been said about the ways that Art Basel has transformed Miami’s relationship to the international art world. Once a year in December, when it’s cold and gray in New York, London, and Berlin, the art jet set congregates in the waterfront hotels of South Beach to buy art, talk shop, cut deals, and party hard. Over the last 12 years, the number of fairs has grown from one to around 20, attendance numbers have reached six figures and the cash injection into the local economy is now estimated at over $500 million a year. The media hype stresses the benefits of high-profile culture, which, like it or not, spurs gentrification on the one hand, and public and private investment in local cultural institutions on the other.

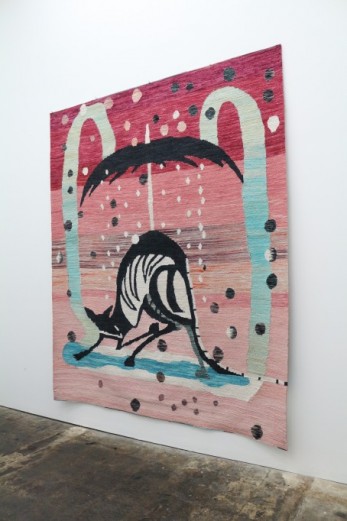

There are two elements of the work in Yann Gerstberger’s recent show that could warrant attention individually: the imagery recalling Miro or Picasso as much as ’80s graphics or ancient, totemic forms; and the work’s material presence as rugs or textiles. Both elements dominate the viewer’s initial encounter. Large rugs of thick strands of dyed mop-head material host mysterious, simple forms in a palette of pinks, magentas, sky blues, whites, tans, and blacks. The atmosphere is warm and light, and the objects suggest ancient modes of making even as they remain obviously contemporary.

Until 2006 it was still possible for the entire Biennale to be hosted inside the KW Institute as well as in vacant buildings in the Mitte neighborhood. But recent development in the neighborhood has forced Biennale’s curators and organizers to expand to venues outside of the city center. While this may have extended travel times between venues, it introduced the artists and audience to parts of the city outside of the expected cultural hubs that have flourished over the years. Most importantly, as noted by Gabriele Horn, Director of KW Institute, it came to reflect the “diversity, social and spatial heterogeneity, dynamism, mobility, and simultaneity of different urban areas that opens up the varied potential for the city’s future and its multiple publics.”

Efficient and peaceful, the Tallinn airport was a marked improvement upon infernal Miami International. The cab driver’s English was better than those in Miami. Come to think of it, everything here seemed better than Miami, especially the weather, which was worse than Miami’s, but simply by being bad offered a change and, with that, excitement. “Nothing is harder to bear than a succession of fair days,” Goethe says. Luckily, with its near-constant cloud cover and regular showers, I didn’t have to worry about that in Tallinn.

On a rainy day in May, the Miami-based artist Christy Gast and I decided to distract ourselves from working on the exhibition project that had brought us to Paris by going to check out Thomas Hirschhorn’s latest installation Flamme Éternelle at the Palais de Tokyo. It was a welcome surprise, upon entry, to discover that Hirschhorn had chosen to make his exhibition free of charge and had built a structure and a communication/signage system that bypassed the admissions desk and descend directly into the massive sub-floors of the art palace. Steered, as we were, by Hirschhorn’s usual language of cardboard, packing tape, and philosophical slogans, we soon found ourselves in what felt like a jerry-built city constructed almost entirely of tires and where the reigning feeling was “anything goes.”

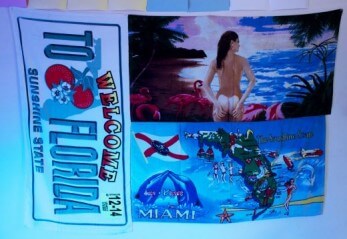

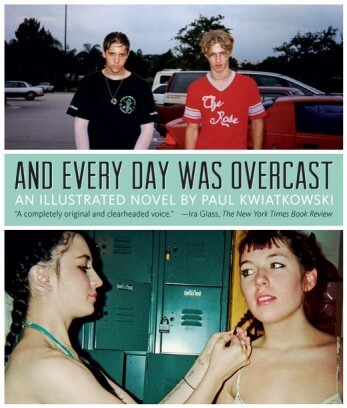

Three Belgian artists, represented by a gallery in Berlin, stage an exhibition in London concerning life in Florida. Chew on that. Chew slowly and hope it stays down. Lieven Deconinck, Gaëtan Begerem, and Robin De Vooght are three multidisciplinary artists who have meshed their names together to form Leo Gabin. For their recent solo exhibition, part of the alternative Inside the White Cube series at White Cube (Mason’s Yard) in London, Leo Gabin addressed Florida as a modern Limbo: where those occupying it lie in wait, in longing but with little hope, for a future above and beyond their current circumstances.

If any city is poised to invent its own idiom, it is here.

In this sprawled out, inconclusive phrasing of a city.

If Miami were punctuation it would be a colon: porous and prophetic.

In the spring of 2013, Miami artists Loriel Beltran, Domingo Castillo, and Aramis Gutierrez started a gallery in Little Haiti called GUCCIVUITTON. I didn’t fully get the irony of the name until I attended an almost empty “collectors night” there, hosted by the Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami. When I asked a museum staff person why it was so sparsely attended, she said “we think a lot of our members drove up, looked at the neighborhood, and kept driving—I mean we’ve had members not come to events because there wasn’t valet, so you can imagine they aren’t ready to stop in Little Haiti!” Despite such collector trepidation, GUCCIVUITTON has mounted some of the most interesting and eclectic exhibitions anywhere, with a sensibility that could only come out of Miami—in fact, that is their stated mission: to explore a colloquial South Florida aesthetic in its many forms. One sweltering afternoon during their Chayo Frank exhibition Gutierrez and Beltran walked me through an oral history of GUCCIVUITTON.

The first time I saw Beach Day perform was from the periphery of a sweaty mosh pit at Gramps Bar in Wynwood, where the band opened up for pop-punk icons the Thermals. Skate videos showing epic, painful wipeouts ran continuously on loop, projected against the side of an adjacent building. A haze of pink lighting enveloped the trio, tempered only by a few Christmas lights slung sparsely and haphazardly inside the small performance tent. When slender lead singer Kimmy Drake introduced herself as “just a Kendall girl,” referring to the blasé Miami suburb known mostly for its Barnes & Noble, audience members stirred restlessly. But then she froze the crowd with vocals that would’ve made Jack White, Kim Deal, and Phil Spector each nod their heads in tacit, rhythmic, hypothetical approval.

Thanks to growing up in Britain, my knowledge of the American West is largely based on The Lone Ranger television show and John Wayne movies. Luckily, these unimpressive credentials did not impede my ability to make sense of, and appreciate, Cara Despain’s exhibition Cast Set, presented in the project room at Emerson Dorsch. Like most viewers, I was able to access the popular tropes associated with the American West utilized by Despain, which the gallery text describes as being “embedded in our collective psyche.” The idea of a collective psyche strikes me as somewhat suspect, since it assumes a degree of exposure to Western culture (in the global sense) that is by no means universal.

Miami’s artists who have been around long enough to have seen and inhabited the city’s waysides—those places just beyond the reaches of gentrification and development, but whose fate will likely meet both—know a familiar narrative. It goes like this: We jump from ruin to ruin and ride out the final stages of spaces bound to meet a very different future, lingering in the dingy moments that comprise its past before it is razed, renovated, or beautified in anticipation of a soon-to-be-changed neighborhood. In the dead of summer, with the hustle of the art fairs and the perfume-soaked, diamond-crusted upper level affairs on holiday, the artists can assemble themselves in their sweaty lair in true form. In this instance, it takes the shape of an exhibition of artists who are working, or have worked, in Little Haiti.

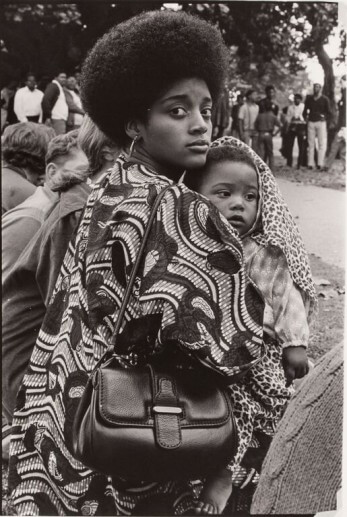

Urbes Mutantes: Latin American Photography 1944-2013 announces itself first as an exhibition of street photography. The mobility of the photograph, the viewer is told, lends itself synchronically to the rhythms and transient excesses that compose the chaos of city life. This evocative intimacy between photography and the frenetic charge of the urban strike a particular resonance in Latin American cities. Such is the curatorial premise of the exhibition, organized by Alexis Fabry, curator of the Poniatowski collection; and María Wills, a curator at the Museo de Arte del Banco de la República in Bogotá; currently presented at the International Center of Photography in New York. Consisting of more than 300 images selected from the private collection of Stanislas and Leticia Poniatowski, Urbes Mutantes offers an incredible survey of photography across 10 Latin American countries.

There is dignity in emerging from the gym, curved from glass, ripe

in the valet wait, all of us, together, breaking under the super moon,

mid-career Drake on the satellite radio, all of us, listening, leather,

fake leather, whatever. There is dignity in the way the wind moves

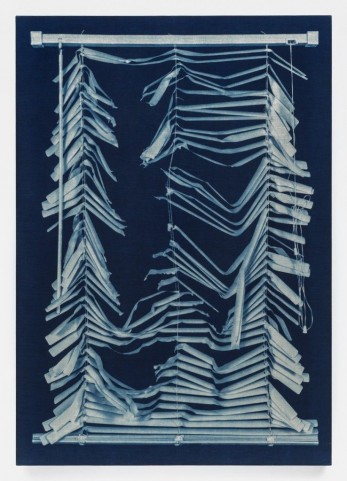

through the palms like a venetian shade in a rented room.

In 1994, when I was Chief Curator for Architecture and Design at the Museum of Modern Art, I testified before the Commission on Chicago Landmarks in favor of protecting the 1951 Arts Club of Chicago designed by Mies van der Rohe. For my troubles I got called a carpetbagger in the city’s newspaper of record. Since then, I have come to realize that name-calling is standard practice in preservation “debates.”

I’ve been involved in a few other efforts to protect landmarks, but I don’t consider myself a preservationist. Why? Because the “ist” in preservationist implies an “ism,” an ideology. And the ideology of preservation—or how it is should operate in practice—is never very clear, at least not to me. Perhaps that is why name-calling is so prevalent as the typical preservation debate plays out like a media smackdown between private property owners and preservation activists, generating more heat than light.

Saturday September 13, 2014 7-10 PM

Locust Projects 3852 N Miami Ave, Miami, FL 33127

Please join us as we celebrate our tenth issue including a special print-only Miami insert!

For her curatorial debút, Kathryn Mikesell of the Fountainhead Residency and Studios selected 115 pieces by local artists influenced by “Miami’s palette, luminosity, and texture.” Seems like a softball pitch, but light and texture is a lot to take on. Down here, it’s up there with Sein und Zeit (right Haden?). That golden hour when the buildings swell, when the light melts flesh like Häagen-Dazs, the grit and rub of stucco and oolite, you know the deal. Calling this city superficial isn’t insulting, it’s taxonomic. But you gotta back it up. To live inside cliché you must be honest.

Handscrawled in pencil near the front windows of the new Swampspace on North Miami (next to Harry’s pizza), Poor Happy is perhaps not the best signage DACRA could have hoped for as the Design District gets thoroughly Bal Harboured. Really, though, this summer group show is less impoverished (and less jovial) than the title belies. All three of the artists are pathetic maximalists, digging through the couch cushions as Saturday morning cartoons blare in the background, coming up with a hoard of cheap or deranged materials that evince a fractured type of American youth.

The story behind Opa-locka is the lore of lore. Like Scheherazade’s stories within stories, it is a nesting doll of myth and fantasy. Sure, the community in Northwest Dade has the most Moorish architecture this side of Tangiers, but it’s also home to scores of nondescript warehouses and commercial buildings. Jorge Sánchez photographs these buildings—the architectural “common denominator,” as he puts it.

For whatever reason, Miami’s art world (and its world world) creaks to a halt in the summer. People flee, or they stay at home and juice. Which makes Meta Gallery all the more frustrating. The curatorial project by Andrew Horton has been clogging my inbox for weeks. Housed in the Locust Projects project room, Horton’s gallery is a rapid-fire assault on our sluggish social calendar. For all of those who want more programing, he’s brought more programing. For those who didn’t, you’re getting the emails anyway.

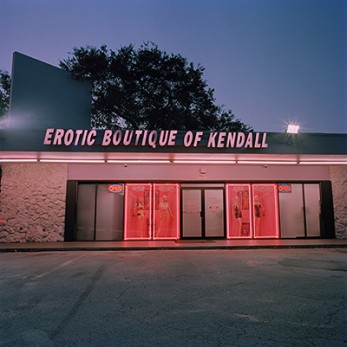

On the back wall of Freshly Squeezed, a trio of pictures of buildings taken by Ivan Santiago are quite similar. Each features the same light: that engorged crepuscular glow that so luridly floods our evenings down here. Each features the same architecture: that drab coral bunker look that speaks of suburban dentistry and hurricane season. And each features the same composition: building slightly cropped, photographed from across a stretch of parking lot, as if the photographer merely pulled over and stepped from his idling car. But there is one difference. The first two include signs (Adult Video Connection XXX and Erotic Boutique of Kendall) that explicitly advertise the salacious qualities of the businesses, but the third does not; there’s just a lone car in the parking lot. Even so, it feels just as sleazy. We wonder, is there something in the architecture itself, in the quality of light, that causes this, or does the feeling just leak in from the other works?

As a high school student flipping around in my AP art history textbook, I would return to group of several thumbnail-size paintings of trees by a young Mondrian. In his affected geometric handling of the branches and leaves, you saw where he was headed. The series of paintings represent less the Modernist program than an artist developing his style, slowly paring away of the inessential. Karen Rifas has done a lot of paring as well.

I have limited experience with songbirds. When I lived in Munich as a small child, we went to visit four distant aunts who shared a small apartment in Kettwig. They had never married because all of the men had been killed. For company, they kept a little bird. This was the first time I saw a bird up close, teetering on a metal tube above a bramble of newspapers, and it was quite memorable, in more ways than one. See, years prior, this bird had been let out of his cage. It might have been the first time, or just one of many regular excursions. But that day, the first thing he did was stretch his wings, flutter up to the ceiling, and then swoop down across the room, right into a full pot of simmering stew. “Ploop” was how one of the sisters described it, her jowls ashuffle. So they scooped him out with a slotted spoon, set him on a paper towel, and waited. The bird survived, but the stew kept his feathers. When I saw him that day, he was completely bald, nothing more than a little kaiserscrotum.

You first see a machete hacked into a row of seven polaroids. Each image is yellowed and distorted by bubbles, which is fine because everyone knows that polaroids are never just about image quality, but about image physicality: the weight and feel, the thing of the image. To take a polaroid isn’t just to preserve a moment, but to listen to that coital grind as the exposed film spews from the camera mouth like Gene Simmons’ tongue.

On the evening that I saw this exhibition, the spiritual and sonic vibrations of Haiti pulsed through the gallery, emanating not from the work on display—a pared down yet far-reaching multigenerational survey of Haitian art in a variety of contexts—but from the church next door. The Look is self-aware on many levels. The art simultaneously basks in and skirts the pale gaze. The gallery, which has been open on 83rd and Ne 2nd for a few years now, is also aware of its conspicuous presence in the neighborhood. To break down those white cube walls, they’ve commissioned a mural from Serge Toissant, the only Miami street artist I’d like to see more of, and hosted concerts and get-togethers over the exhibition’s run. Had they planned it, the chants coming through the wall would have been a nice touch.

Flat Rock at the Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami, is Virginia Overton’s first solo exhibition in an American museum. The new freestanding sculptures that Overton created for the show are tenuous yet forceful assemblages of materials the artist encountered around Miami and on site at the museum. The exhibition begins with a large-scale fountain that Overton created for the museum’s pond. In the gallery, she addressed the existing architecture by arranging long planks of lumber to create two parallel lean-to walls; this rudimentary architectural device carves out a long passageway that viewers must navigate before entering a diagonally warped exhibition space.

The exhibition is strewn about the Museum of Art Fort Lauderdale. “Scattered… as stepping stones for the viewer’s passage through time and space” says the museum’s materials. The videos’ peppered arrangement falls quickly into place, acting as nodes of cultural critique, autonomously growing in the rubbed joints of the museum’s authority. Fabri’s “Me and Them” (2005) is one of the first pieces you encounter upon entering the museum’s expansive lobby.

It all begins with a proposal that no one, barring roughnecks lacking any degree of sensitivity, would disagree with: the world is moving too fast. This is also unfortunately becoming a bit of an alibi to not have to think too hard. As the distribution of information accelerates and the hierarchies that once determined the value of its units vanish, experience is impoverished.

The Insomnia Crisis that permeates Karen Russell’s Sleep Donation is already pumping vigorously through the story in the opening pages, but it quickly begins to spread. Insomnia is akin to a zombie plague, but for those readers who are too familiar with endless hours of restless sleep or have experienced jet lag that sucks melatonin to abysmally low levels will find similarities to the horror in Russell’s new traipse

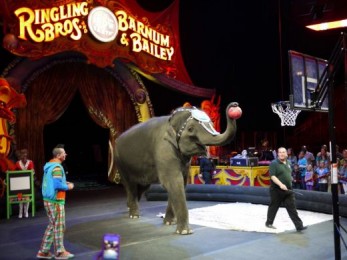

Approximately one fifth of all elephants in North America are in the Sunshine State. A hundred out of 475.

African or Asian—a mix—and like many people and beasts, they mostly came south for the weather.

According to John Lehnhardt, Executive Director of the National Elephant Center (NEC) outside of Vero Beach, it is easier to keep the animals in a warmer locale because they do not have to be brought inside when the temperature approaches freezing. The elephants adjust because Florida more closely parallels their native tropical climates. And it doesn’t hurt that they have acquired a healthy taste for the Florida Valencia oranges that grow on the former citrus grove where the facility is located.

Writer and curator Sarah Sulistio talks to L.A.-based artist Harriet “Harry” Dodge about his video practice and participation in the upcoming biennial Made in L.A. 2014 (June 15 – September 7, 2014) at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. Harry Dodge’s video Unkillable (2011) is featured in Video Container: Touch Cinema at the Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami (May 15 – July 6, 2014), organized by Sulistio. This interview was conducted over email.

If you maintain even a slight interest in humanity or, at least, have a keen set of eyes, you might’ve stumbled upon notes or photos or objects set adrift from their rightful owners. Grocery lists, unsent notes, half-torn documents, withered and aged photographs: in thrift stores or on the Metrorail, they are abound—floating, fragmented pieces of the human fabric. Writer and founder of Found Magazine Davy Rothbart has shared these pieces of strangers’ lives for the past fifteen years.

Florida drives always take longer than they are supposed to. We took the back roads to Venus from Miami and paid two hundred dollars for what Jacque Fresco refers to as a brain enema. At the end of the drive there were two guys from Toronto wearing yoga pants, a Pittsburgh pair, one with a furry beard, the other with fur boots, one milky white youngster from Copenhagen, and a statuesque couple with hardly identifiable accents. We were greeted by a man with a ponytail who opened a large gate that read The Venus Project. Suddenly, a compound of dome-homes (perfect for withstanding hurricanes), lush non-native greenery, hungry raccoons, and one sleepy alligator surrounded us as we made awkward introductions.

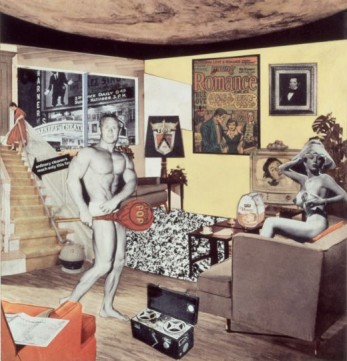

Richard Hamilton famously claimed that for him, Braun’s industrial design was as inspirational as Mont Sainte-Victoire was for Paul Cézanne. The sleek modern lines of Braun’s eponymous toasters were his phenomenological muses. This analogy provides great insight into Hamilton’s eclectic body of work.

Gravity and Grace holds satisfying contradictions: huge, humble; shimmer, trash; detail, big picture; spectacle, substance; industrial, craft. The scale of the monumental wall works is impressive, and the recycled materials they are constructed out of, curious. Like a magpie or a family of raccoons, we indulge in the multitudes of flattened metal scraps—bottle caps, tin-can lids—that comprise the works, and marvel at the mind-numbing labor required to produce them.

The tumble of first impressions went something like this: Street photographs. Striking colors. Not that large. In-your-face portraits—faces that looked as worn-out as old rugs, others full of confidence and a beauty rendered more intense by the way that what they were confident of was that the beauty wouldn’t last, so that the confidence too was touched by resignation.

The title of the group exhibition at David Castillo Gallery, Metabolic Bodies, implies that the strategy of using manipulated readymades is a corporeal action, a chemical change that transforms a substance (in this case found images or objects) into energy.

Reflecting television’s ability to both mirror and influence America’s middle class, in 1957 Lucy and Ricky Ricardo moved from Manhattan, where they had lived since 1951, to the suburbs. Rob and Laurie Petrie arrived in 1961, Samantha and Darren Stevens in 1964, Michael and Carol Brady in 1969. Helen and Morty Seinfeld moved there in 1989, but its unlikely their son Jerry or his pals are leaving the city anytime soon.

For all its regular crowd of artists and writers and creative hangers-on, the porch still isn’t Soho, or Greenwich Village, or even Coconut Grove. But it isn’t Hialeah, either.

The high-fives break out instantaneously like a saloon brawl.

Five dollar bill in front of the Kwik-Stop.

Surprise party patrons in paper hats crouching

underneath the dinette set. Spider web.

Bubble wrap. Kick-ass. Apollo pulling the stink of the night away

from his V-8 supercharged chariot. The stimulus check

comes in the mail! The stimulus check is cashed!

The work of Russell Maltz hovers in the fragile beats between two frequencies. One is the mark-making impulse of the human, while the other is the homogenous system of distribution of the inhuman. In his assemblages of generic building materials—concrete masonry units (cmu), metal studs, PVC pipes, and plywood—there are actions and operations rather than conceptual compositions. Thus the show title situates Maltz’s work as neither self-consciously elevated nor counterproductive.