Futurism, Fascism, and Italianità

Hunter Braithwaite

Renato Bertelli, Profilo continuo del Duce [Continuous Profile of the Duce], Bronzed terra cotta, 1933.

The Birth of Rome

Rendering War

The Wolfsonian-FIU

Through May 18th, 2014

Take the opulent elevator up to the seventh floor of the Wolfsonian, and as the doors clink open, you first encounter a Futurist bust of Mussolini. It’s all profile, all of the way around, a panoptic visage that sees and controls all, but strangely dodges the gaze of the viewer, a peculiar denial of dictatorial hero worship. The bust is bronze, emphasizing the connections between modern man and the missile, but closer examination reveals that it is actually painted ceramic, an unexpected allegory for the exhibition (and period) in toto. Also unexpectedly, Il Duce looks like a buttplug.

What follows is three exhibitions laid out over two floors that show Italian artists, designers, and architects at work in the interwar period, attempting to synthesize an Italian style (Italianità) that matched both the peninsula’s long cultural history and its much more truncated history of political identity. As to what this Italianità entails, it’s classical tropes—naked boys, olive branches, that heavy-teated she-wolf—registering somewhere between camp and threat, all polished up with a Modern sheen. The bright colors and streamlined curves throughout the top floor’s Echoes and Origins are trademarks of the Liberty Style, Italy’s version of Art Deco.

Lucio Fontana, Servizi espressi per tutto il mondo [Worldwide Express Services], Offset lithograph, 1935.

Stefano Borelli’s Fiat Trophy,bronze and marble, c. 1935.

Even the materials used have an unexpected connection to politics. After the invasion of Ethiopia in 1935, Italy was hit with League of Nations sanctions that blocked the importation of many materials, thus forcing designers to experiment with new materials. A fiberglass and aluminum writing desk from that same year (designed by Clemente Busiri Vici) is a fantastic example of this. Aluminum was a common material during the period due to Italy’s wealth of bauxite mines, bauxite being a common aluminum ore. Next to that are two wall works made out of linoleum. Linoleum, although invented in England in the 1860s by Frederick Walton, is etymologically Latinate (linum + oleum), and thus was appropriated by the Fascists as something of Italian descent. If one leaves the jackboots at the door, fascist interiors work quite well.

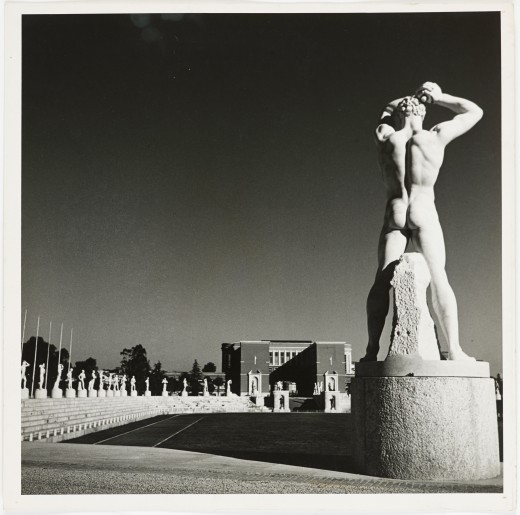

Downstairs, The Birth of Rome shows five plans for Rome embodying the city’s eternal importance. The Augustean zone, the Foro Mussolini, the plans for a new city by Futurist architect Virgilio Marchi, the plans for the Esposizione Universale di Roma (EUR), and the Italian Pavilion for the 1939 World’s Fair in New York all present speculative and actual updates to the ancient capital.

George Hoyningen-Huene, “Photograph of the marble stadium, Foro Mussolini,” Gelatin silver print c. 1937

The joke is that Italy got behind Mussolini because he made the trains run on time, and many of the architectural and urban developments of that period (both on display here and not) helped form a modern nation. But this transformation was not without its absurdities. Take the punitive-sounding architectural program of sventramenti (disembowlments) and isolamenti (isolations), whereby Rome was returned to its former grandeur by taking historical ruins that had been updated by architectural renovations and then stripping away those additions, effectually re-ruining them.

Finally, another show presents an unexpected twist on the Fascist figure. Rendering War: The Murals of A.G. Santagata shows groups of charcoal drawings meant to illustrate the Case del Mutilato (the Association for Disabled and Invalid War Veterans) in both Rome and Genoa. One of the tenets of Fascist representation of the figure is that bodies are strong, virile, and young—and so these are. But to remember how it must have felt for wounded veterans to look at these stocky-limbed bodies. I don’t mean look up as in idolize, but actually look up, from the low perch of a gurney or a wheelchair. Nowhere else in the show is the gap between ideology and actuality so strong.

Giacomo Gabbiani, 1919, Oil on canvas, 1931.