On Contemporary Regionalism in South Florida

Cara Despain

Guests in front of Henry Flagler’s 1,150 room Hotel Royal Poinciana (demolished), Palm Beach, 1886. © Flagler Museum Archives.

The term regional, as applied to contemporary art, can siphon away interest from all parties. Artists are often reticent to adopt the adjective because they don’t want to be confined to the apparent or assumed identity of a place. Regionalism can also be viewed as lacking in criticality because of its close proximity to folk art, and therefore can be perceived as that which has failed to achieve local escape velocity and enter into a larger, more global dialogue. But it seems that as the centers of the art world become increasingly untenable for artists who have not yet arrived, remaining in the periphery affords quicker opportunity. This dissolution could also provoke a renewed interest in regionalism, or a new form of it altogether. Miami is an art center for one week out of the year, and is then relegated to the status of outlier once more. This creates bifurcated circumstances for artists that live and work here year-round. But unlike many other off-path cities, there is at least a varying international audience, a cluster of major art collectors and a fair amount of resources available to proportionally few artists. Miami has resisted much of the homogenization that has occurred in the majority of mid-sized cities in the U.S. and has maintained a unique character that is the result of many complicated factors. How does this translate to regional, contemporary art practices?

The term Miami Vernacular has been brushed upon in town, but the discussion seems to be locally confined. The slippery task of regionalism is to assert a sense of place and identity outside of itself, but to do so in a way that does not look like a cousin of nationalism, or like an inferiority complex. Are there discernible commonalities that have developed and appear in work artists are producing in South Florida? I cannot suggest that I am able to quantify Miami-regionalist practices or assign colloquial aesthetics, but I’m interested in this phenomenon and the perplexities it exhumes for places with complex identities.

Art Deco house in Havana. Courtesy University of Miami Special Collections.

It’s more than just the existing conditions in the local art community that inform the cultural aesthetics of a place. It’s a compression of time and development: land, settlement, immigration and all of their corresponding microcosms. (Simply put, the broad must be understood in order to understand the niche.) Because climate and resources dictate settlement, land use, navigation and ultimately social development, landscape is a key preexisting condition of regionalism. The climate and topography make South Florida a temperamental convergence of vastly varied wildlife and vegetation. It is a strange and hyper-sensitive ecosystem that can require a lot of patience to appreciate—which stands in paradox to the intrinsically enjoyable warm weather and water that Florida is almost comically known for. The conditions in the still-wild areas can be as harsh as they are beautiful—unbearable mosquitoes and biting flies, and suffocating humidity with non-existent shade or solid land is not what many tourists expect from a national-park experience. Though people are fascinated by crocodiles, alligators, and Burmese pythons, not many actually want to run into them in the wild—much less in shallow, muddy, isolated water. Though the land here is emphatically flat, elevation is major—just a few inches difference means a different habitat with different resident creatures. It’s almost as if the social/urban landscape metaphorically echoes the dynamic of the natural landscape, where having any significant height (a view) invariably means having money.

The natural world is constantly at losing odds with development, receding back like hair from an ever-encroaching wasteland of forehead. The Everglades National Park is the federally designated remainder of the native landscape, and even that has undergone drastic decay due to invasive species and human intervention. South Florida’s land was fetishized as a wild paradise for the purpose of tourism by early hotel magnates, and has been altered through landscaping in a way that upholds this fantasy. Native grass and plants are smothered with edged lawns, and native trees replaced by more recognizably tropical but imported vegetation. Though people know swamps exist in Florida, they don’t want to stay in one.

The revision of the natural landscape can be observed in any Miami neighborhood—from Buena Vista to Star Island (itself a manmade repository for celebrity wealth). But the extended version of this extravagant dream sought after by multiple generations departed from the actual landscape decades ago. There is a new landscape—a cacophony of concrete, glass, coral, neon, Art Deco and Miami Modernism; parking garages and high-rise condos. Though characteristic, the decadence that coagulates at each shoreline like VIP hopefuls at an exclusive soiree is not the only dimension of Miami’s constructed environment. There are also large expanses of destitute neighborhoods, skeletons of condos whose exteriors were never stuccoed, shotgun houses in every color imaginable and areas and roadways in varying states of decay. This dichotomous urbanscape is immensely significant in analyzing the topic of regional aesthetics and practices in Miami, but it must be addressed after examining the history, use and loss of the natural landscape.

The subtropical unsettled territory of South Florida was a curiosity for wealthy business folk and industrialists looking to extend their ventures while wintering in a warm locale. If you visit the Flagler Museum in West Palm Beach, you can see where a large part of this story begins, and how the imported mimetic palatial and European aesthetics spawned at the Whitehall estate have continued to affect our visual psyche via permutation. A far cry from Whitehall’s opulence, many local dwellings defined by formica, illusionistic marble finishes, and yard statues painted white so many times that they morph into inelegant blobs are familiar sights clinging dubiously to classical motifs. You might also think of imported wealth and class. The didactic information makes many rather propagandist statements, but this one from the brochure might be my favorite and the most telling: “Everything else you see and do in Florida will make more sense if you start by visiting the Flagler Museum.”

Henry Flagler, a Standard Oil man, is credited with everything from Miami’s fatherhood to South Florida’s tourism and agricultural development. True to expansionist form, he is responsible for taking his railroad to the southernmost point of the country: Key West. But, of course, this history of modern development is only one contributing factor to the region’s cultural composition. It leaves out the natives who resided in the area for thousands of years prior, early Spanish explorers and, later, the Latin and Caribbean immigrants and Cuban refugees. The architecture and municipal conditions reflect this somewhat diametric history.

Miami’s different immigrant groups have preserved much of the tradition, religion, ritual, language, culture and ornamentation from their countries of origin—which creates a striking aggregate that has become an entire visual lexicon of symbols in itself. The wealth divide is vast, yet different classes and income levels abut one another frequently; third-world conditions transform to manicured extravagant high-rise living within one block’s distance. Objects and allusions are tucked everywhere, a chicken corpse in the street is just one example.

Today, Miami has a complexity that is at once magical, frustrating and misunderstood. It’s a winter respite for New Englanders and Europeans, a gateway to Latin America, and ground zero for lightning strikes and Carnival cruise ships. Any of this information can be gleaned from a shitty travel guide or The New York Times. Though a destination, Miami is not a center, and this creates a sort of predicament when it comes to the question of art production here. How do artists who reside here permanently, seeking validation in the larger art world from a position on the periphery, simultaneously engage or associate themselves with the region’s layered identity?

While limiting in some regards, it seems some of the deficits the city has in comparison to places like New York or L.A. have actually precipitated a productive DIY mentality that results in critical experimentation and artist-run spaces and initiatives—many of which (such as Bas Fisher Invitational and the end/SPRINGBREAK) even promote regional-centric programming and exhibitions. As the city itself has patchy infrastructure and a sense of lawlessness, the art scene too has few models in place with no written rules. There is still much uncharted alternative territory in Miami. There is not yet a feeling of overabundance with spaces such as apartment galleries or homeless art organizations. A sense of newness still persists with such projects, which lends them excitement, support and agility. Artists bring their own rules and superimpose them on the existing hollow structure, and, as a result, are able to do whatever they want without much repercussion.

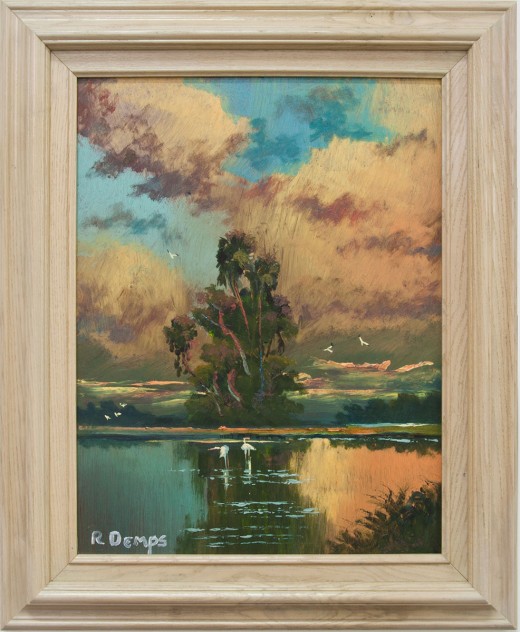

From my vantage point, this compendium of history and the present conditions of South Florida manifests itself in a few interlacing ways in the work being produced here—through re-examination of tradition and a self-reflexive interpretation of a hybridized environment and cultural identity. A recent exhibition at Guccivuitton, a new artist-run gallery in Little River, surveyed South Florida landscape painting in a continuum of contemporary reevaluations or continued trajectories and tradition. I had a conversation about the larger topic of regional aesthetics and the aims of the gallery with Aramis Gutierrez, who directs the space along with fellow artists Loriel Beltran and Domingo Castillo. The exhibition contained works by Scott Armetta, Brian Booth, Juan Carballo, Mary Ann Carroll, Willie Daniels, Rodney Demps, Phillip Estlund, James Gibson, Jason Hedges, Daniel Newman and Charles “Chico” Wheeler—five of whom were a part of the Highwaymen group (Carroll was the only woman). On top of being a pertinent exhibition to this topic, the space aims to facilitate and explore colloquial aesthetics.

The name Guccivuitton started as a joke after the three co-directors observed a marketing tactic that utilized brand hybrids and designer knock-offs for products aimed at refugees in the Little River neighborhood. Finding this strange practice of selling a transplanted identity humorous, they adopted a combo knock-off name themselves. The idea to uphold a localized reflection in programming followed. Hybrids, both in art and architecture, are a product of Miami’s imported global influences and aesthetics and the way they collide with the existing conditions. Gutierrez reflects on how this provides source material for artists:

A lot of artists here are working through their regionalized experiences from the remnants and detritus of a post-apocalyptic consumerism fallout. This manifests itself in the club-heavy collages of Pepe Mar, to the reassigned chemical components in the work of Nicolas Lobo or the proposed narratives of Christy Gast. To say that this way of working is symptomatic of the most recent global recession would be a vast oversimplification. This is because South Florida is not only the crossroads of Europe, North and South Americas but also the depository of the cultural hybridization that’s left in their wake. I am suggesting that it was already in our disposition to sift and re-compartmentalize because of our transient cultural composition.

Merely mirroring the quotidian environment in an aesthetic practice in Miami would inevitably reflect some sense of specificity, and a sort of gather-and-synthesize process of artistic production does seem to have emerged. There could be a corollary to this in the current conditions artists are working within that extends to the landscape—of which there are also mere reconfigured remnants left. Remnants of land lost, subjugated, inundated.

Rodney Demps, Swamp Cluster, Oil on Upson Board, 17 x 21.” Courtesy of Guccivuitton.

Landscape painting is often regionalism’s first stop, but only in particular cultural conditions does it become a necessity. The younger artists in the show don’t have to use the scenic as a safety net or sell paintings to tourists, but they are still interested in this legacy. “The tradition of landscape painting has carried on both in spite of and [as a result of its abandonment by] contemporary art,” says Gutierrez. “The conditions just happen to be in place for artists working in a continuative approach, like landscape painting, to be contextualized in a contemporary art setting open to revisionism.” And they do pick up where the Highwaymen left off in a surprisingly straightforward way. This unabashed, sincere pursuit is notable when considered against the backdrop of the contemporary art world and all its esoterics. It could be argued that most of the Highwaymen likely did not intend for this contextualization, but that these younger artists also resist it suggests an open interest in maintaining regional practices in contemporary settings. Interestingly, the Highwaymen paintings are the more blithe mementos next to the more ghostly and decayed pieces by the younger artists, an arrangement which underscores the motivations of the respective groups. It was deeply necessary for one to paint an ideal for others—and of interest for the other to perhaps deconstruct this ideal in order to portray a reality more similar to the unsettled and disappearing land.

Contemporary regionalism is perhaps a subconscious endeavor to promote and preserve localized sensibilities that are eroding in the wash of globalization. Critically reevaluating tradition while simultaneously extending it is an effective balance, and is one among many responses to the stimuli and conditions presented here. South Florida’s natural landscape and geographic position are the preface for a larger conversation about colloquial aesthetics—one that has many facets. The conditions here are a starting point, the uninhibited attitude of Miami’s art scene has ignited a frank yet cool discussion laced with introspection. Whether there will be a Miami School is yet to be determined. But I venture to say that there is something here that is not anywhere else.