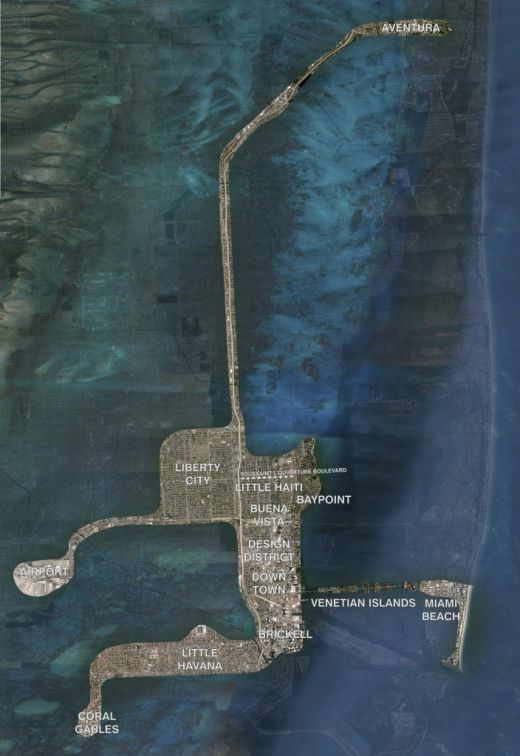

A map the author made of his trips in Miami.

My vision of Miami is influenced by the two texts “Generic Objects” (2010) and “Learning from Little Haiti” (2009) written by Gean Moreno and Ernesto Oroza, which I read before flying to the city. The first one describes the structure of the systems of objects conceived by capitalism as cogs of its function. In this regard, it is interesting to observe that the capitalist production is relatively indifferent to the design of its commodities—the stock exchange, its most extreme embodiment, does not even include a material commodity—on the other hand, the design of the systematic infrastructure is cautiously thought to provide optimal efficiency to its function. Moreno and Oroza thus describe how the norms in terms of containers, palettes, ships, cranes, and highways around the world have composed a holistic metric system allowing the globalization and acceleration of capitalism. In a conversation I had with them, we evoked the possibility of infiltrating the system, using these fluxes of goods and its various lubricants. Moreno and Oroza insist however in the impossibility of sabotaging—that is, etymologically and historically, putting a clog in the machine’s cogs—the system, because of its unstoppable indifference:

“Its indifference, its inwardness, the silence generated by its centripetal flows, should terrify us. It is monstrous in the way its energy absorbs all forms and meanings.” (Moreno and Oroza, Generic Objects, 2010)

This essay is illustrated by photos taken by the author, often with a camera phone, often from a bicycle.

In contrast with the skyscrapers of Downtown and the villas of the Venetian Islands, such an architecture reveals the social disparity that a city like Miami produces. I would like to insist on the term of production here as I use it intentionally: architecture is certainly not the only producer of social disparity, but not only does it crystalize social antagonism, it fuels it via the process of gentrification. In a beautiful auditorium of Coral Gables, five white architects, critics and curators—only one woman—declare their pride of curating and/or constructing the buildings that put Miami in the international spotlight. Someone in the audience asks a question about Liberty City, an impoverished neighborhood just outside of that spotlight, and one of gentrification’s future targets. One of the five architects recognizes honestly that he does not know how architects can resist this process. The others acknowledge “a problem” while undertaking perilous explanations about the fact that Liberty City’s current inhabitants—essentially African Americans—do not have as bad conditions of life as we usually assume. They continue to suggest that gentrified populations have the means to negotiate the terms of their role in the process with developers and politicians. It is difficult to determine if these architects were being disingenuous or absolutely disconnected from the reality of gentrification, which, in just a few years, evicts people from a neighborhood where they sometimes had lived all their life. While architects like to think that they do not share responsibility for the economic and political violence of gentrification, they are part of this process as much as other decisive actors, since it could not fully enfold itself without an architecture that corresponds to the needs of the gentrifying population. Bodies (often white) that move to neighborhoods subjected to this process do not simply move there: they bring with them a sphere of comfort that substantially modifies the economics of the place. Wine bars, cafes and expensive grocery stores open, the police department starts to operate for the neighborhood and no longer against it, and new buildings get built. The price of real estate thus rises, which facilitates the transition of a working class population to a middle-class one. Gentrifying architecture reflects how the latter group cannot accommodate itself with the current conditions of the neighborhood, and materializes their fears of the otherness by considerably increasing the security of the building and the exclusivity of those allowed inside.

In this matter, the cartography I made of Miami is the one that my bicycle flânerie has allowed me to accomplish. The photographs that accompany this text are instants of this drift that contextualizes my experience of the city. The speed that one reaches on a bicycle is interesting as it allows a body to move through the atmospheres of different neighborhoods, an openness that cars and buses lack. It is also more flexible than public transportation, which, in many cities, including Miami, is almost segregative due to its limited network. Establishing the car as the default mode of transportation, as is the case in many American cities, consists of an aggressive politics of denigration for people who can’t afford one. Those populations find themselves contained within their own neighborhood and denied of their “right to the city,” as theorized by Henri Lefebvre in his 1968 book.