Martine Syms: Nite Life

Nina Johnson-Milewski

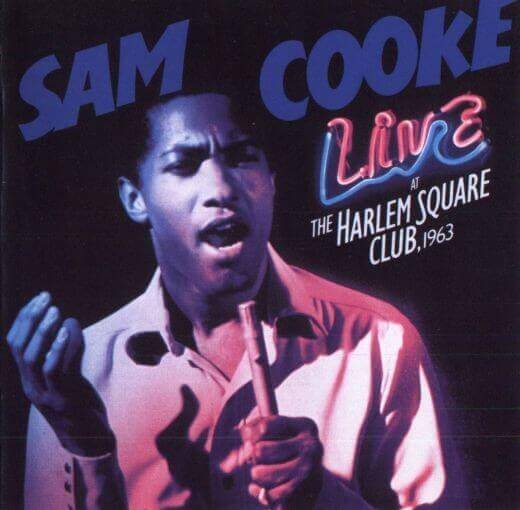

The cover of Sam Cooke's record, "Live at the Harlem Square Club, 1963"

The cover of Sam Cooke's record, "Live at the Harlem Square Club, 1963"

April 14, 2015

I saw a sound check version of Martine Syms’s Nite Life, which seems fitting for a work that investigates a raw club recording made in Miami in 1963 by Sam Cooke that wasn’t released until decades after his death. I heard a few comments after the actual performance that mostly dealt with the discussion about which category the work might fall under: is it an artwork? Is it merely a lecture? From where does its merit come? Increasingly, we see artists or cultural producers creating work that exists between boundaries.

A lecturer I recently heard argued that, in part, this is due to the depletion of funds in other avenues of creative production. Of particular mention were students that would have previously studied poetry, seeking MFAs and creating “alternative, text-based works.” I am not sure that any of this dialogue about which category artistic production falls into matters, but what I do think matters is an interest in a more experiential form of learning, of sharing knowledge, a practice that stems from interdisciplinary interests ranging from graphic design to performance, music, dance, and visual art.

There’s a tradition of storytelling that is particularly relevant in the black community. Artists such as Terry Adkins, Clifford Owens, Shinique Smith, and many others have drawn on this to create contemporary works that engage the audience in an immediate sense. You can hear this tradition in Cooke’s recording, which leads the audience through a narrative, manipulating our engagement through various highs and lows and drawing from a collective experience as black individuals in a segregated America to do so. In the case of Syms’s piece, there is a certain anthropological perspective, an unearthing of a very specific piece of material that I found most engaging, particularly in an age where music and recordings are mostly shared as singles via digital streaming services.

The relevance of a tangible object in culture today is often discussed via the art market and in terms of objects of high value, or as fetishized objects such as limited edition record prints and singles. But the Cooke recording is a raw work intended, partly, in its originality, as a live performance for a particular audience, and partly as a “live” recording album release (Cooke’s record company decided the recording was too raw and feared it would alienate his white audiences). The orator of Syms’s performance, Danielle Rollins, argues that the 1963 Overtown audience was “his” audience, a crowd among whom Cooke was allowed “to be himself,” a crowd that wouldn’t consider him “too black” and as a result, there is an honesty in the music that transcends time and media.

When researching Syms and her work, I was struck by the description of her on her website as a “conceptual entrepreneur based in Los Angeles.” As entrepreneur, Martine assigns the task of walking the audience through her presentation and the historical narrative of Cooke’s life to an orator, a singer, who periodically chimes into song, engages with the audience by asking questions and ad libs through the facts with personal anecdotes and proclivities. As an entrepreneur often presenting works in contemporary art contexts, where should the viewers’ expectations of Syms lie? Is it important to mark boundaries of context and, specifically, how do these questions relate to the cultural economy? All these questions seem relevant to ask through the lens of an album created in 1963 by a black artist requiring the same contractual dues as Elvis Presley, held in an archive by a system of distribution determining the sonic boundaries of culture.

This work was presented at a bar, not a museum, gallery, or auditorium… and its companion piece, a printed banner of text, wraps a parking lot in Miami’s most rapidly changing luxury destination, the Design District.