Thomas Lawson with Hunter Braithwaite

Hunter Braithwaite

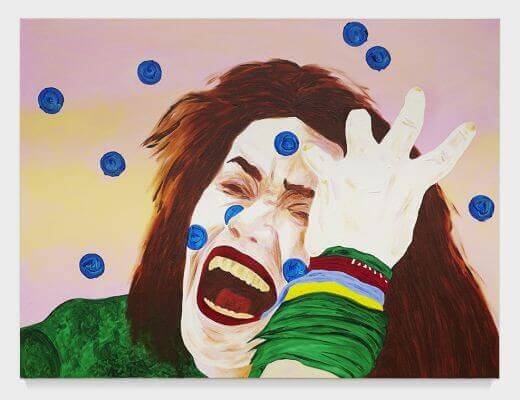

Thomas Lawson, Disastrous, 2015. Oil on canvas, 76.2 x 101.6 cm. Courtesy David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles

For three and a half decades, Thomas Lawson has remained one of the most articulate voices in the field of a painting. Both an artist and a writer, he is also editor-in-chief of East of Borneo and the Dean of California Institute of the Arts. On the occasion of Last Exit: Painting at the Bakehouse Art Complex, which was curated by CalArts alum Justin H. Long in response to Lawson’s seminal 1981 essay of the same name, Hunter Braithwaite speaks to Lawson about painting— its current state, how it can be approached through writing, and its ability to capture the “vagaries of the moment.”

HUNTER BRAITHWAITE (MIAMI RAIL): In addition to painting, writing, and teaching, you’re the editor-in-chief of East of Borneo. How has that publication affected the LA scene?

THOMAS LAWSON: East of Borneo grew out of an earlier project called Afterall, which was a collaboration with a publication in London. When I started, it was quite difficult to find writers in Los Angeles who were interested in contemporary art. This was around 2000 or 2001. Since then, a whole new generation of writers has appeared, which is great. They’ve come out of the art schools—the writing programs at Art Center and CalArts. I think the best-known is Michael Ned Holte, but there’s also Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer, Jennifer Krasinski, Andrew Berardini, and Travis Diehl. They’re part of the scene, they’re in the social networks, they go to the openings and hang out in people’s studios. They’re participating in the whole dialogue, and I like to think that by giving them a local platform we have helped to grow that.

And something that’s unique about East of Borneo is we encourage our readers to become collaborators, to work with us on developing a user-friendly archive of Los Angeles art and its history.

RAIL: Is East of Borneo updated regularly?

LAWSON: We’re online, so there isn’t a monthly issue in the old print sense, but yes, we publish commissioned essays on a regular basis and have a fuller program of uploads to the collaborative archive. Actually, in the last few weeks we’ve just posted two pieces. One was an interview that Rita Gonzalez did with Kerry Tribe discussing a recent work that was shown at 365 Mission Road. And the other was a piece that Jonathan Griffin wrote about Roger Brown, who’s mostly associated with Chicago, but lived out here for a while during the last years of his life, built a house and studio in a funky little beach town up the coast, just north of Ventura. Jonathan has a nice piece about that.

We’ve just moved into a new office down in the city, off campus. The campus is kind of at the edge of the city, so it’s not really well connected. Now we’re renting a space from the Women’s Collective for Creative Work. We’ve only been there a couple of weeks, but already people have been dropping by, coming in with suggestions, so it’s feeling like a good move. It feels more like we’re in the middle of things.

RAIL: If you Google “painting” today, almost every article deals with the market, collecting, and flipping. Just what is it that makes today’s paintings so marketable?

LAWSON: That’s actually never been my particular experience. [Laughs.] I’ve always found it quite possible to make paintings that are not market-friendly. I came of age during the first wave of slagging off on painting because it was something that was just marketable. The deep irony of that moment in the ‘70s is that it was the beginning of the marketing triumph of the Conceptual movement, which was engineered entirely by a group of who we would now call gallerists and museum directors.

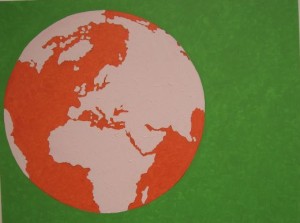

Thomas Lawson, Untitled/Orange, Pink, Green, 2006. Oil on canvas, 60.9 x 91.4 cm. Courtesy David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles

There is an amazing academic study by Sophie Richard that lays it all out. 1 What Richard does is track very carefully how a select group of artists were placed in significant exhibitions and given gallery representation even as these very artists were protesting that they were doing nothing like that, that they were against the idea of career and market success. They did the standard career building that any artist would do, but they were doing it in the name of a group that claimed they weren’t doing it. To say it’s cynical is too strong, but they did what they had to do to make their art visible, and it’s just kind of ironic because part of the rhetoric was claiming that the generation of artists before them or even some of their peer group, like Brice Marden, were pandering to the market. For them to call the kettle black always struck me as deeply suspect. The market is a characteristic of contemporary art, you can’t pin it to one particular medium.

Thomas Lawson, Portrait of New York, 1989/91. Industrial sign paint on plywood, 15 panels, 243.8 x 243.8 cm each. Originally installed at Manhattan Municipal Building, New York. Courtesy David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles

RAIL: Was this one of the first death knells for painting?

LAWSON: The first calls for the death of painting were back in the nineteenth century when photography happened. In the contemporary world, it’s the late sixties—the dematerialization of the art object and the privileging of process over product. There are funny and ironic things [from this period], like Mel Bochner making these deconstructions of painting by arranging newspaper on the floor and adding some color, or scattering things around based on an arithmetical model. Now he’s a painter, doing sort of interesting work with language in paint. And it’s like, yeah, of course, because that’s what art is, you use what you have to use to get the effect you want. Any given artist may focus on one singular medium, but describing art and valuing art through medium choices is just the wrong way to frame the argument.

Painting is just a way of making art and it’s a way that I find satisfying, because it allows for personal intervention that is subject to the vagaries of the moment. What strikes me as the enemy is the spectacular, seamless illusion, the unbelievably well-crafted media flooding our consciousness just to sell crap. That’s the nightmare that envelops us. And the art that I respond to takes issue with that. It finds ways to contest it, or ignore it, or gather around it in some way. Some strategies to do that are classically conceptualist, some more performative, and some are painting. That’s where I stand with that. I like painting because I’ve always liked painting. I like images. I like translating images from one place to another and seeing what happens, and in doing that finding ways to open up thought.

RAIL: Can you give me an example of someone’s practice that attempts to slow down this process?

LAWSON: In terms of old dead guys, Sigmar Polke is a classic exemplar. He was willing to experiment with the material and experience in a way to upset expectations.

RAIL: Have you seen anything interesting lately?

LAWSON: I went to the William Pope.L show at MOCA during its last weekend at the end of June. It was a fantastic show and I was feeling kind of stupid for not having seen it sooner. The centerpiece was an installation of a gigantic American flag with one extra star. It was being blown by these huge special effects fans—the kind the movies use to create a storm scene or something. Over the course of the show, the wind generated had been so fierce that it had ripped the flag. So it was shredded and very dramatically lit. It was an impressive image and we saw it like a week after the tragedy in South Carolina and then the long-overdue recognition that the Confederate flag represents racist-inflamed treason. There was something about the resonance of the flag that just seemed particularly strong. It was a great piece.

RAIL: Siebren Versteeg, one of the artists in the exhibition at the Bakehouse, has used algorithms to randomly “paint,” either on a constantly evolving screen, or a physical surface. What do you think about artists using technology to such a degree?

LAWSON: Wade Guyton has done some pretty spectacular things with the computer and the printer. That’s definitely an avenue, but to me it depends on what the actual individual is trying to do. Here’s a difference in my thinking since 1981. “Last Exit: Painting” uses the theoretical framework of the Frankfurt School to make claims for history. I don’t really buy that so much anymore. I think it’s too generalized to be all that helpful.

I think now we need to look at artists and think about how the combination of technologies that they’re employing deliver what they’re trying to deliver. That’s the test, not whether it’s world historical. Is it coming across, does an audience get into it and see what it is? In my case, I use technology in the process, but the end result is hand-painted. For me that’s important because I value that sort of individual mark making with all the error-prone, dysfunctional aspects.

RAIL: How do you use technology in your paintings?

LAWSON: Not in the production, but in the overall process. I always start with found materials. Images are gathered and manipulated, fiddled with and thought about on the screen, and then at a certain point I leave the screen and get onto the canvas. So part of the work gets done in that digital space, but most of it is done by hand and eye. I wouldn’t make any claims to being at the forefront of technology, but we’re in a world where it’s there, and it’s a really handy tool, and you use it.

RAIL: You exhibited work in 2014 at the Goss-Michael Foundation in Dallas. In one room, there was a close-up portrait of a boy’s face, a grid of nine figures in space, and then a person holding a decapitated head. Can you tell me a little bit about this room? What is this body of work?

LAWSON: That show was sort of a mini-retrospective, so the works are from different periods. The grid of drawings is actually from 1977, when I was still a very young artist. I was thinking about a certain kind of psychologized space— interiors fractured by reflections. Before making the drawings, I used to build little models with pieces of mirror, cardboard, and toys. So that was definitely pre-technology. [Laughs.]

RAIL: And the face?

LAWSON: That’s from the period of “Last Exit: Painting.” At that time, the New York Post did a lot of front-page stories about crimes that were targeted at young people. They would print a photograph of some victim—most often it seemed to come from high school yearbooks, some sort of weird non-picture picture—along with an inflammatory headline. So my process was to go down in the afternoon and buy the paper and see if there was something I could use. If there was, I’d start making a painting. They were square monochromes, and I was thinking of them in some kind of dialogue with the paradigm structures of minimalism. The one with the severed head is more recent, from shortly after the invasion of Iraq. It’s an image from the Internet of a jihadi who beheaded somebody. At that point, I was working with two kinds of images, often placed together. One set of paintings were based on images of world maps, images that were not the usual Western view of the globe with the Atlantic in the middle, but from different perspectives. I did a show at LAXART [History/Painting, 2007] with these works juxtaposed with a group of smaller images of various decapitations. Some of them were basically news images and some were based on Baroque paintings of John the Baptist. I was thinking about geographical and historical continuity. The Middle East has had this sort of terror fascination with decapitations since biblical times. It’s about the erasure of consciousness: when you are engaged in an ideological battle it’s not enough to kill your enemy, you actually have to remove his mind. It’s a pretty astonishing thing. I didn’t install that show [at the Goss-Michael Foundation], but I did like that wall, because it outlined the way my thinking had changed, in part because of changes in technology—from building an imaginary space in the real space of my desktop, to finding information in the newspapers on the streets of New York, to finding information on my computer screen, in the Internet space.

RAIL: Having just seen the Sarah Charlesworth show at the New Museum, I can’t help make a connection between your grid of figures floating in space and her series Stills, of people falling.

LAWSON: That’s a good analogy. We were working at the same time, thinking about similar ideas.

RAIL: Were you friends?

LAWSON: Friends is maybe too strong, but acquaintances. At that time, she was married to Joseph Kosuth, who was very sociable. He used to have parties in their loft, and he would invite people out to Mickey Ruskin’s bar, and pay for dinner. So, yeah. [Laughs.]

RAIL: You mentioned painting’s ability to capture the vagaries of the moment. Speaking of painting and the vagaries of this moment, did you see Forever Now at MoMA?

LAWSON: You know, I’m going to do a painting seminar next spring, and that show is going to be my starting point. It was an interesting show, but it was a frustrating show. Part of the frustration had to do with how badly installed it was.

RAIL: They were kind of crammed in there.

DB14, Dallas Biennial, 2014, Goss Michael Foundation, Dallas. Courtesy David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles

LAWSON: It was just crowded. The previous time I’d been to New York, I saw the Whitney Biennial and it was also badly installed and also featured some of the same painters. I thought, “God, these poor people are getting all this attention, but at the same time they’re being jammed up one against each other in this way that seems very unfriendly.” For me it was a kind of painting that was more about the processes of material, which never seems quite enough. This is just for me personally. I feel that imagery is usually an important aspect. So I always find that for more abstract forms of art making, while it’s interesting, and I can get the point, I feel a little bit left wanting. Someone like Barnett Newman does it for me, but it’s because of the transcendence and that’s not really possible anymore.

RAIL: Is that why you’ve always stuck to the figuration in your work?

LAWSON: I’m a member of the Pictures generation. My whole process begins with looking at pictures. I’m enthralled with what is being depicted, what’s been chosen, the way it’s been presented, thinking about what it’s intended to mean, and what it maybe unconsciously means. These are all things that generate my activity. When I’m starting a new series of work, I collect a certain kind of image. That’s just where I start. I think someone who is more process-oriented is doing something, going back to that phrase you used, more in the moment. They’re experimenting with something materially and I get that, I’m just not particularly into it.

RAIL: In an essay about Laura Owens, you wrote, “every artist faces the dual problem of ends and means, what to do and how best to do it.” How does this apply to the art writer?

LAWSON: You know, I have this analytic mind sometimes, and sometimes I don’t. Writing requires a different concentration from painting, and they’re not always in sync. I do find that I want to know why something is compelling. So I start writing about it and doing research into where things might have come from. Sometimes I look at other people’s work for clues. It’s part of the larger process of thinking through the work. When I was younger, not so much anymore, it was also about claiming a space for the work. There was a certain polemic to it. Particularly the reviews in Artforum back in the early ‘80s were pretty combative about declaring space. “This is interesting; this is not,” that kind of thing. Following in the tradition of Donald Judd, or something like that.

RAIL: Do you find that it shifts from artist to artist, like what we were talking about earlier, abandoning the world-historical scope of a Frankfurt school type of critique, focusing instead on a case-by-case basis?

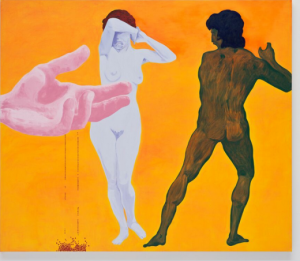

Thomas Lawson, Endurance, 2012. Oil on canvas, 182.9 x 213.4 cm. Courtesy David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles

LAWSON: When I started writing it was for art magazines and what I wrote was a combination of polemics and the beginnings of trying to figure out where my own thinking was. Now I’m more of an elder statesman and I’m asked to write catalogue essays to give some perspective on another artist, usually a younger one. That’s a different task, I now try to understand what that other person is doing, obviously within the limitations of what I’m thinking about at any given time. I’m not doing the polemical thing anymore, which is why these bigger world-historical questions don’t really have to come up.

RAIL: In the same essay, you list three expectations the writer encounters: the expectation of the artist you’re writing about, the curator involved, and the reader. Is there a hierarchy of loyalty? Is there someone you write the essay for more than for anyone else?

LAWSON: You’re writing for the readership. You want to be clear and you want to be persuasive, so there’s that. But you’re also writing for the artist, because you want to be accurate and honest. And because it’s not my primary activity, I need to feel like I’m getting something out of it, too—learning something. That’s how I think of it at this point. I’m in my mid-sixties, so I’ve gone through a lot of different kinds of experiences about how you think and how you make. I tend to be much more reflective now than at the beginning, when I was being very proactive. It’s an interesting question, with a shifting answer.

RAIL: You’ve written about how, because of numerous social conditions, California has had a different relationship to painting than New York and northern Europe. Do you believe these geographical distinctions are still in place, or has the globalization of the art world and the ease of moving from place to place created more of a homogeneous relationship with the medium?

LAWSON: I think there are still geographic specificities that control things. When you think about the history of modern art from a New York perspective, there is a history about painting or antagonism to painting. Painting is a major feature of it. But when you think about the history in LA, its not. It’s about more diverse kinds of practices with an almost literary aspect, a way of performing out a proposal, like Wallace Berman or Mike Kelley or Chris Burden. That’s what has given solidity and seriousness to the project out here. Painting is just one option out of many, which I think is a good place for it to be. Someone like Laura Owens doesn’t ever think about the death of painting. It’s just not a useful kind of thinking for her, so she’s just not engaged in that and doesn’t need to be. I think it’s been liberating. So yeah, I do think that there are significant differences. I have an idea of a book that would explore, from a historical perspective, this idea of LA being more theoretically grounded and experimental. I have a box full of notes for this book, but it’s such a lot of work, I don’t know if I’ll ever get to it.

Hunter Braithwaite is a writer and editor based in Memphis, Tennessee.

1 Sophie Richard, Unconcealed, The International Network of Conceptual Artists 1967–77: Dealers, Exhibitions and Public Collections (London: Ridinghouse, 2009).