The Love Song of R. Buckminster Fuller: Review + Interviews with Sam Green and Ira Kaplan

Kevin Arrow

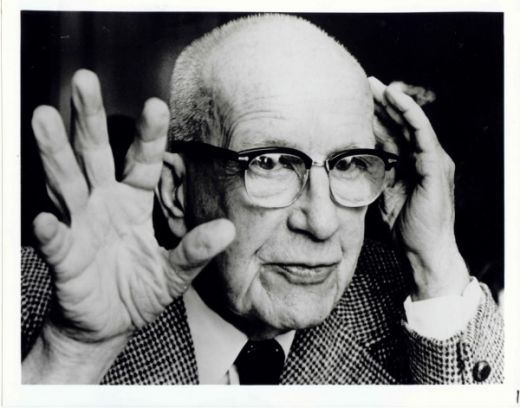

Buckminster Fuller in 1978. Photo: Fred Blocher.

A master of self-mythology, Fuller referred to himself as “an engineer, inventor, mathematician, architect, cartographer, philosopher, poet, cosmogonist, comprehensive designer and choreographer.” In the 1960s you were able to do that and he was rarely questioned about his credentials.

Much of what I thought I knew about the world in the 1960s and ‘70s slowly unraveled as I got older. The Age of Aquarius ended and my counterculture super heroes, much like the Wizard of Oz, turned out to be ordinary guys working behind a fancy curtain. Yet Fuller had no reason to self-mythologize; he was alive and working during one of the most creatively fertile time periods of the 20th Century. He was friends with Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius, he was on the faculty of the progressive Black Mountain College with Merce Cunningham, John Cage, and Josef Albers.

Fast forward to March 22, 2014. The setting is the 415-seat Colony Theater, a beautifully restored 1935 Paramount Pictures movie house on Lincoln Road. The narrator is Sam Green [1966, Detroit, MI]. The film is The Love Song for R. Buckminster Fuller, a live documentary, with musical accompaniment by legendary rock band Yo La Tengo. It aims to tell the story of Fuller as Fuller may have liked his story to be told. Running a total of 55 minutes, I am sure Fuller would have felt this was merely an introduction. Known for time intensive endurance lectures, it wasn’t uncommon for Fuller to piss down his leg instead of pausing for a bathroom or meal break. A single 42-hour lecture is posted online and you can, according to Green, “listen to six hour chunks while you are sitting at work,” but I am getting ahead of myself.

Green is set up on stage right, along with a microphone with floor stand, chair, small table, and laptop computer that was all bought from my company. Stage left is Yo La Tengo, along with Kurzweil and Casio keyboards, drum kit, bass guitar, two electric guitars, acoustic guitar, and organ. Formed in 1984 in Hoboken, N.J., Yo La Tengo is Ira Kaplan, Georgia Hubley, and James McNew. They are well known for their ability to collaborate and improvise in a seemingly effortless manner, and are considered to be all around great people to work with. The band accompanies Green at each presentation of the film since it was commissioned in 2012 by The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. There were no vocal microphones on the band’s side, indicating that it would be an evening of Yo La Tengo instrumentals.

By including a live band, Green chose to have a very ephemeral approach to Buckminster Fuller. Although Fuller’s life work seems to be driven by replication and regimentation; it is organic at heart. Film’s ability to grow and morph would have likely pleased Fuller, whose influence is continuing to affect new generations. The Miami presentation opened with scenes of the Miami Seaquarium’s Golden Dome designed by Fuller in 1960, along with a brief introduction to local photographer and longtime Fuller acolyte, Mark Diamond.

R. Buckminster Fuller appears in projected form on a large movie screen in the center. The house light dim, the band takes the stage. For the opening of the presentation Ira Kaplan plays keyboard, Georgia Hubley plays organ, and James McNew plays acoustic guitar. The music begins with a light and bright composition; it has the quality of a march or an anthem. This provides the soundtrack for historic black and white footage of a Fuller dome being flown by helicopter and placed into an empty field. There is a voiceover of Fuller describing his ideas of Ephemeralization—the ability of technological advancement to do “more and more with less and less until eventually you can do everything with nothing.” I enjoy the image of Fuller’s dome and spoken words descending from on high. This sets the tone for the entire presentation: a combination of hope and dread. It is Fuller’s ideas and their inability to rise up and float on their own which soon becomes apparent. The helicopter and the life work of Fuller seems anchored, tethered, and bound by the time and technology from which it is trying to escape. Whereas Fuller’s story is rife with missteps and near misses, the band provides a soundtrack that gives the story a sense of wonder and optimism. They provide fluid transitions from scene to scene and seamlessly surge forward during dramatic moments and recede during the times that Green, Fuller, or one of the on-screen experts is speaking.

After the show, during the Q & A session I was unable to contain myself from asking Yo La Tengo to consider picking up their instruments and playing one more song. I pointed out that we were all sitting in the audience; they were on the stage with their instruments and we all had nothing but time. After a minute of huddling together they walked over to their instruments and gave us one more amazing free form instrumental improvisation. Sam Green commented afterwards that this was the first time they ever played an encore. You’re welcome.

Sam Green in 2011. Photo: Joanna-Eldredge-Morrissey

KEVIN ARROW: Hi Sam, what do call this type of project? I thought of it as an expanded documentary, do you have a specific term for it?

SAM GREEN: There are a lot of different terms I use, and the truth is, this is a kind of funny thing, I use different names for it in different contexts. For the film world I call it a live documentary. Expanded documentary works good too, I like the reference to expanded cinema, that’s kind of cool. In the performance world I have called it a performance, or lecture-performance, that’s a whole kind of genre within performance. We have also done some screenings in libraries before where I just call it a fancy lecture. These terms are malleable and loose.

ARROW: What was the main source for archival material?

GREEN: All the material comes from Buckminster Fuller’s Archive, an enormous archive in which he saved tons of photos, film footage and stuff. Practically and conceptually everything came from one source.

ARROW: Where is the Buckminster Fuller Archive?

GREEN: Stanford University.

ARROW: How did it end up there?

GREEN: Stanford bought it. Fuller’s archive is noteworthy because it’s the biggest archive of any individual that exists and he was very methodical; he poured tons of resources into it, spent his entire life accumulating this archive. It consists of all the things that ever passed over his desk. Many people have stated that in many ways it is his most impressive work.

ARROW: It seems that when Fuller was alive he was aware that his work was of vast importance, although others may not have viewed it the same way. He was highly regarded in his lifetime, yet also overlooked.

GREEN: Yeah, for sure. He was thought to be sort of a kook. No architects thought of him as an architect, and designers thought he was too weird. In many ways he was marginalized in every arena he was working in.

ARROW: Are there any documentaries you remember influencing you when you were growing up?

GREEN: Yes, this is a little of obscure, but when I was in college I had a job showing movies in classrooms during the old 16mm-film days. I showed a movie in a religion class called Holy Ghost People. I was totally mesmerized by this film, it was a vérité documentary shot in the ‘60s about a snake handling church in Appalachia and it was so fucking good. It was by a guy named Peter Adair, who I didn’t know at the time but he turned out to be an accomplished filmmaker.

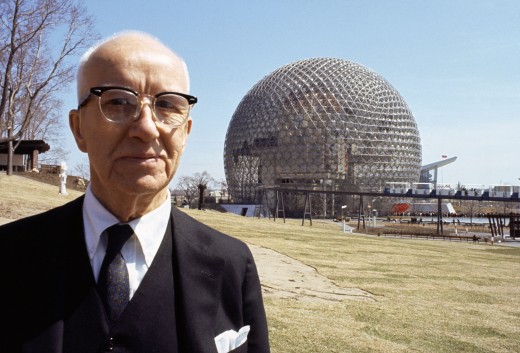

Buckminster Fuller with one of his iconic geodesic domes.

GREEN: Yes, for sure it is the practical part of it. I always get a thrill out of being in situations that you never would otherwise be in because you are making and researching a film. That is one of the best parts about it. In truth I don’t make films to get access to stuff, I make the films to try and figure out why this thing is under my skin.

ARROW: Can The Love Song for R. Buckminster Fuller eventually be released as a conventional film in which the narration and soundtrack are brought together with the film?

GREEN: No, part of what I like about the form is that is ephemeral and that would undermine this. There is something about the liveness of the event that you don’t get with a video. I am happy to allow it to just continue to exist as a ephemeral thing.

ARROW: How did the collaboration with Yo La Tengo manifest?

GREEN: The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art asked me to make the piece. They were organizing a show on Fuller, and they requested a live film and music thing. I had been a big Yo La Tengo fan and I knew that they were very good with music and movies. I am friends with Emily Hubley, who is the sister of Georgia Hubley. Emily is an animator, and both Georgia and Emily’s parents, John and Faith Hubley, were early influential animators. Emily put me in touch. I asked them if they be interested and we went back and forth. They were in-between records and they had some down time and they said sure. We made the piece together, so I gave them a bunch of footage that I was interested in using and they made some sketches of songs. I then went to their rehearsal space in Hoboken and we just kind of went through it and cobbled it all together. It was a very fun and collaborative experience, unlike other director-composer relationships.

ARROW: The Love Song for R. Buckminster Fuller seems to be a positive-messaged project as Fuller was a complete idealist, while The Weather Underground (2002) is a darker story. They seem to be the best and the worst of the ‘60s and ‘70s—both highly unusual and flawed.

GREEN: I wouldn’t necessarily agree with the best and the worst; they are both interesting. What I like about Fuller is that he had this moment in the 1960s but he had started doing things in the 1920s and went all the way into the 1980s [Fuller died in 1983]. Even though he is known for is being that “dome guy” in the 1960s, he really is a lot broader than that. That is what interests me. I like people like Joseph Cornell, or people who have had careers that were very, very long, and spanned a lot of eras. They are both manifestations of a certain energy and impulse in the 1960s. Fuller was definitely positive, the piece is mostly positive, but I like to make fun of him a little. He was such a kooky character. It’s hard to take him 100% seriously, but I do have very positive feelings about him.

You can critique him. Adam Curtis, the BBC filmmaker who made a piece about him, was pretty critical about Fuller and his worldview. In some ways, there is a critique that can be made. If left to his own devices, he would have torn down all the old buildings and we’d all be living in domes. I don’t know how great that would be.

ARROW: There would be no corners. It seems as if Fuller had an aversion to corners! You were born in the 1960s and it would seem that you missed out on a lot of these things first hand. Raymond Pettibon, a visual artist and sometimes filmmaker, is re-imagining these decades and cultural developments through his own personal lens. I guess this is similar to what you are doing.

GREEN: Yes, I was a teenager in the 1980s, and I would wonder how the hell the 1960s became the 1980s. It didn’t make any sense. In a way the Weather Underground movie was trying to understand what had happened. It really doesn’t make any sense how you can go from the 1960s to 1980s. There is this very fascinating period, the ‘70s. They weren’t like That ‘70s Show, but a very rich time that resists the clumsy stereotypes. The Weather Underground was a movie about the 1970s.

ARROW: Can you tell us a little bit about what you are working on now?

GREEN: I have several things, I have a new live movie that I just premiered at Sundance last month and I am starting to do shows with that. It’s called The Measure of All Things, and is very loosely based on the Guinness Book of Records. Today, I am editing a short film for the music group the Kronos Quartet.

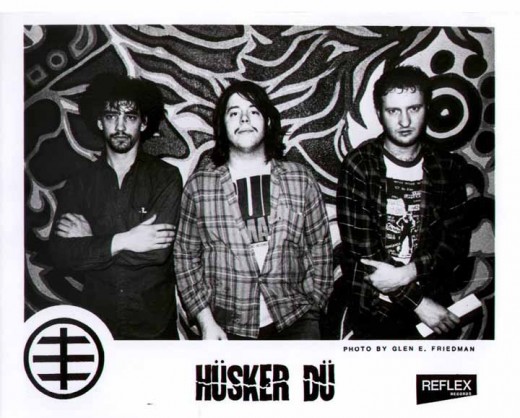

Yo La Tengo’s Georgia Hubley, Ira Kaplan, and James McNew. Photo courtesy of Matthew Salacuse.

Yo La Tengo’s Ira Kaplan

KEVIN ARROW: Hi Ira, sadly I missed your last visit to Miami. The one and only time I saw you play was in the mid 1980s at CBGBs. It was an odd tribute show in which you shared the stage with Peter Stampfel of the legendary Holy Modal Rounders, and Greg Norton, the bass player from Hüsker Du. Do you remember any of the details of that unusual show?

IRA KAPLAN: No, that is not true!

ARROW: I was there!

KAPLAN: (laughs) We have never played with Greg Norton before!

ARROW: I was there, Ira, and I remember it clearly! You mean you’ve never played with Peter Stampfel?

KAPLAN: We have played with Peter many times, just not with Greg.

ARROW: Ok, it was the 1980s and if you remember anything from the 1980s then you weren’t there!

KAPLAN: (laughs) I’ll have to do some research!*

*UPDATE: Later that day I realized that it was Tony Maimone of Pere Ubu fame who played with the band in 1988. Ira graciously provided this follow up via email:

It was August 5, 1988 CBGB, NYC with Peter Stampfel, Amy & Will Rigby, Jad Fair, and Chris Nelson on trombone. We played the following set: Griselda, That’s What I’ll Do, I Can’t Make It on Time, Alrock’s Bells, Tail of a Star, Sh-Boom*, Alyda, Yellow Sarong, A Teenager in Love, Get Off the Air, You’re Gonna Miss Me// Emulsified.

I was also confused by your saying we played with Peter Stampfel. Of course, we did, in that he was on the bill. But I thought you meant that he performed with us, which he did not on this date, although he has on various other occasions.

ARROW: Anyhow, I love that fact that Yo La Tengo has collaborated so often over the years. It is one of the things that you do so well. I particularly like the placement of your music in the films of Hal Hartley. How did that relationship develop?

KAPLAN: It started when he simply began licensing our songs. I think “Drug Test” may have been the first one for Surviving Desire (1993). He licensed songs for several movies. During the course of that we met and we asked if he’d make a video for us and the “From a Motel 6” video happened. We actually gave him an idea we had which we thought might be the germ of something and what he did with it was almost unimaginable. So that was pretty great. Then our appearance in The Book of Life (1998) had a slightly more collaborative aspect to it. I wouldn’t exactly call our working with him collaborative. I’d say we were just pawns in his game!

ARROW: Can you cite any note worthy collaborations? I know you have worked with Yoko Ono and Matt Groening.

KAPLAN: There are certainly too many to name. Most years, starting in 2001, we would play all eight nights of Hanukkah at Maxwell’s. We very quickly got into the habit of bringing people up on stage with us. The very first night Terry Adams of NRBQ sat in for our whole set. The number of people we have thrown together for those shows makes a very long list.

ARROW: Yes, everyone is on the list except for Greg Norton!

KAPLAN: (laughs) Yeah, that’s true, it’s funny we have never played with any of those guys, and we have done shows, and festivals with Bob [Mould] and Grant [Hart], but I don’t think we ever shared the stage with any of the members of Hüsker Du, which is almost shocking.

ARROW: Well perhaps it’s something to consider for 2014. Are there any dream collaborations you can think of?

KAPLAN: Well other than Hüsker Du… I have ducked that question over the years mostly because one thing I have learned is that I am not really big on setting goals. If you set a goal saying ‘one of these days I am going to play with a member of Hüsker Du,’ then it’s like my dream didn’t come true and I guess I failed but all these other things happened, and you are not really enjoying what’s going on and your just distracted by this goal you’ve set for yourself.

KAPLAN: I think they both quite imaginatively saw how the world could be a better place. I think they both quite imaginatively and artistically recognized how the world wasn’t necessary listening to them and they did not seem to get discouraged by that. They took that as a greater spur to creativity. During the show, you will see lots of people listening to Fuller, but nevertheless a lot of the things he had to say then are no less true and are actually truer today, so they might have been listening but they were not following.

ARROW: I used to do a Sun Ra only pirate-radio broadcast here in Miami. I would go on at midnight and play music and spoken word until 2 a.m. I am happy to know that Yo La Tengo covered the song “Nuclear War” (1982). Did you record any other Sun Ra songs?

KAPLAN: Yes, we have done other ones too. We have had the opportunity to play with the Sun Ra Arkestra on occasion.

ARROW: Do you remember what your first rock concert was?

KAPLAN: I do, it was the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, and Tim Buckley [08/19/1968].

ARROW: Where did you see them?

KAPLAN: It was at Wollman Rink in Central Park. For many years they used to have a great series of shows in the early evening that were youngster friendly.

ARROW: In 1984 you chose the name Yo La Tengo [Spanish for “I have it”]. Can you share its origin?

KAPLAN: During the 1962 season, New York Mets center fielder Richie Ashburn and Venezuelan shortstop Elio Chacón often found themselves colliding in the outfield. When Ashburn went for a catch, he would scream, “I got it! I got it!” only to run into Chacón, who spoke only Spanish. Ashburn learned to yell the phrase, “¡Yo la tengo! ¡Yo la tengo!” instead. In a later game, Ashburn happily saw Chacón backing off. He relaxed, positioned himself to catch the ball, and was instead run over by left fielder Frank Thomas, who did not understand Spanish and had missed a team meeting that proposed using the words “¡Yo la tengo!” as a way to avoid outfield collisions. After getting up, Thomas asked Ashburn, “What the hell is a Yellow Tango?!” This story is where we learned the phrase, but we named ourselves that because we liked that it didn’t mean anything in English, and it sounded musical and kind of essentially meaningless so we could impose our own meaning on it.

ARROW: Are you season ticket holders for the New York Mets?

KAPLAN: No, I follow them closely but I don’t go that often. I am kind of the cranky-old-man sports fan and am always decrying this and that. I listen to the games when I’m in the car, and I’ll watch them on TV when I’m at home. One of the great pleasures of being a Mets fan, and they are frequently few and far between, is that their TV announcer Gary Cohen is really fantastic. The broadcasts they have been doing for the last couple of years with Keith Hernandez and Ron Darling are great. They’re a great broadcasting team so we can only hope that the playing on the field will match the broadcasts.

ARROW: What are some film soundtracks that have impressed you over the years?

KAPLAN: Bruce Langhorne’s soundtrack for the film the Hired Hand [1971, dir. Peter Fonda] is a big favorite around here. We love Burt Bacharach’s soundtrack for After the Fox [1966, dir. Vittorio De Sica], that’s another. I am trying to avoid saying Ennio Morricone, because that goes without saying. You mentioned Krautrock earlier and that’s just a hop, skip and jump to the Goblin’s work with Dario Argento.

ARROW: Can you speak a bit about the Sounds of Science score written for surrealist filmmaker Jean Painlevé’s beautiful underwater science films in 2001?

KAPLAN: The San Francisco International Film Festival spoke to us about scoring a silent film. They sent us a bunch of silent movies and there were a couple of things, but nothing leaped out. Then we had another conversation with them and someone else at the festival had been thinking about the Painlevé movies. They said even though they have scores and narration in French, the narration is subtitled, so we just turned off the volume and wrote new scores. We were not familiar with his movies. They sent a VHS with a bunch of them and that was just perfect and that’s how it started.