Julian Schnabel, Large Girl with No Eyes, 2001. Oil and wax on canvas. Collection of the Artist © 2014 Julian Schnabel / Artists Rights Society (ARS,), New York.

HUNTER BRAITHWAITE (RAIL): This November marks 35 years since your plate show at Mary Boone. What do you remember from that show?

JULIAN SCHNABEL: I felt pretty good then. I was obviously curious to see what other people would think of those paintings because I hadn’t shown them. I was pretty excited about those paintings. When people saw them, the response was…well, the response changed my life. There was a lot of activity after that. A lot of conversation, a lot of people entered my life. It was one of those moments that people imagine.

RAIL: How old were you?

SCHNABEL: I made the first plate painting in the end of the summer of ‘78. I was 26 when I started making them. I’m 62 now, but I haven’t grown up much.

RAIL: This fall, your work is featured alongside Francis Picabia and J.F. Willumsen. Are you excited about this new historical read?

SCHNABEL: Is it exciting now to do this show? Yes. You embark on this project to have a discourse with people who have affected you in some way. You’re communicating with dead people, but their art is alive, and you don’t know how extensive that dialogue is going to be until you live for 40 years. J.F. Willumsen was born in 1863. He died in 1958. Picabia died in 1953. I was born in ‘51. Those guys didn’t even know that I was going to be born. But now I guess the curators thought my work could serve as a barometer. Willumsen was seen as an iconoclast his whole life. Luckily, he had a rich wife, and could live outside of society. It’s very interesting to look at his work with 20-20 retrospect vision, in the same way you’d look at late Magritte.

RAIL: You’ve said that “Signaturizing is getting paid to stop thinking… Signaturizing is a trap. It is artists believing that their work should always have the same appearance.” Over the past three and a half decades, your work has rarely had the same appearance, but it often has the same presence. How have you managed to expand so widely yet still maintain a coherent body of work?

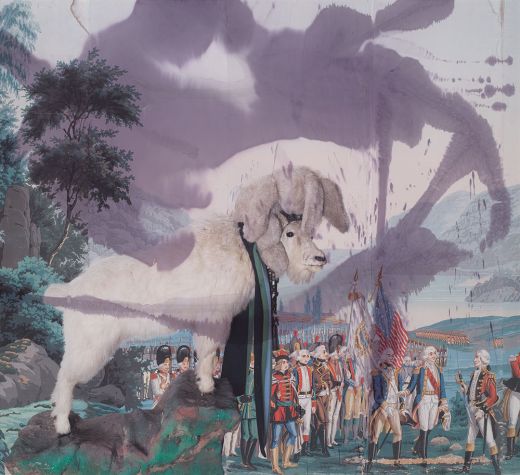

SCHNABEL: That’s a good question. I didn’t find an irreducible image that—as an art object—was the end-all as a representation of what I was. As my need changes, the appearance of my work changes. I kept dealing with different ways of making paintings, different ways of making a mark, experimenting with scale. The work has the same attitude but looks different from work made in a different time. There was a painting I made in 1986 called “The Migration of the Duck-billed Platypus to Australia.” That painting was painted on a drop cloth that was black corduroy. There was a Tonka truck sewn on it. That painting gave birth to a lot of different paintings. I’ve taken things that have existed in the world and commandeered their meaning for a new set of meanings. Whether it was plates in the plate paintings, or a photograph of a stuffed goat that I superimposed over an image of DuFour wallpaper from 1850, like the goat painting that’s in the show.

Julian Schnabel, The Sky of Illimitableness II, 2012. Inkjet print, ink on polyester, 130 x 142 inches. Private collection, New York. © 2014 Julian Schnabel / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

SCHNABEL: You just try to find the best people to deliver the lines. Luckily, I’ve had the opportunity to work with some great actors. A lot of them came to me because they liked my paintings. Gary Oldman, Dennis Hopper, Chris Walken, Javier Bardem, all were interested in painting. The best artists, the best actors are always the best listeners. Good actors are like sponges. They absorb everything. My favorite actors are the most curious, about the world, about other people, about things they don’t know about. Somebody once asked me about the difference between painting a portrait of Andy Warhol and directing Javier Bardem in a movie. You have a responsibility to the actor, to the sitter, to not let them fall through the cracks. It’s a collaboration—just like a collaboration between assassin and victim. [Laughs.] I don’t do it for money, so I take enough time to make the film the thing that I want it to be, rather than to be rushed by the studio or a distributor.

RAIL: You refer to your painting “Fountain of Youth” (2012) as Whitmanesque, in which “all things are equal, just different elements, images on the same plane.” Are there any literary figures or movements that have inspired you, or have factored into your paintings?

SCHNABEL: There are writers who speak to you. William Gaddis’s The Recognitions had a huge effect on me. When you start filming books that you read, you start to learn them in a totally different way. But with Walt Whitman, the notion of everything existing on a horizontal plane is what I’m talking about. There’s no hierarchy. It gives you the possibility to do anything. Obviously that’s a pretty wide possibility, so you have to decide what you want to do. If I think of Walt Whitman, I think of Bill Gaddis, his use of language and simultaneity of time gave birth to a lot of paintings of mine. I started making these paintings on Army cots, and I wrote words from The Recognitions on them, so the subject and the material was the same thing.

RAIL: And then there’s the tension between real and fake in The Recognitions, the original, and then what came after.

SCHNABEL: Everybody’s got their own version. You could hear “Concierto de Aranjuez” on flamenco guitar, or you could hear it played by Miles Davis on horn. There’s no personal language, there’s just a personal selection of language.

RAIL: With “The Diving Bell and the Butterfly,” how did you manage to visualize the main character’s experience?

SCHNABEL: Different physical things dictate your reality. For example, he [Jean-Dominique Bauby] can’t move his head. If you go to the right, he’s not going to see you. You have to stand in the middle. So you realize that you can have a figure walk off the screen. You don’t have to frame it normally like in other films. It gives you all types of opportunities to adjust to that point of view. Also, the guy was seeing out of one eye. If the doctor says, “We have to sew your eye up, it’s getting infected,” you can put your camera inside his head and sew his eye up. It creates a lot of different possibilities that wouldn’t be available to you if you had a normal guy that was your subject.

RAIL: You’ve been in the papers recently regarding the work you’ve done with the Brickell Flatiron, a new condominium in Miami. With this project, with Palazzo Chupi, simply by painting wall-size works outside so that they’re exposed to the elements, we’ve seen domestic architecture thread through your work for a long time. Can you speak to that continued engagement?

SCHNABEL: I think that people want to construct their environments. For me I was lucky enough to build a place that I found comfortable. If you can’t build one, just find a place that you like. I don’t know how it happened that I started making work that was so connected to architecture. When I looked at certain spaces I would just see something.

You know I made three paintings for the Maison Carrée in Nîmes. They were there for five years. [The Maison Carrée, built circa 16 B.C., is one of the best-preserved Roman Temples in the world.] I like old buildings. I don’t think progress is necessarily denoted by big glass boxes. Again, there are things that I make that are personal to me; there are materials that I like. I never thought about it much. I guess Bonnie [Clearwater] had some notions about building environments, or about the film set. I kind of look at making film like I’m making sculpture. You try to make people feel like they’re having an authentic experience, so they can have a room with a view, although maybe it’s an interior view.

RAIL: What was the inspiration for the Maison Carrée paintings?

SCHNABEL: The building was the inspiration. The fact that Caesar built that place for his daughter. I went there. I looked at the walls. I made the paintings.

Installation view of Café Dolly: Picabia, Schnabel, Willumsen at the Museum of Art Fort Lauderdale. Photo courtesy the museum.

SCHNABEL: I’d never heard of Willumsen before. The curators came to visit me in Berlin and showed me some of his work in reproduction. I thought that the idea of connecting him and me through Francis Picabia would work. There’s a whole notion of these paintings being time maps—paintings being not what they seem to be, or alluding to things outside of what might be the most recognizable quality. There’s a lot of experimental attitude in Willumsen’s and Picabia’s work that is an alternative to the normal trajectory of Modernism.

RAIL: And what about Picabia?

SCHNABEL: I’m a huge fan of Picabia. When people see the exhibition they can see the connection themselves. The fact that he was included as a connector between the two of us had a huge effect on my decision to be in the show. I think he’s a great artist, a singular artist. He did things that made his friends turn their backs on him because he took his own path. That was not obvious to the people of that time, but as time passes, we see the importance of his contribution and how valid the work is.

He took things that seem to be ordinary, that people didn’t consider as art. He painted what he wanted to paint. At the turn of the century he painted abstract paintings, but he painted calendar girls in the ‘30s. He’s going against the grain. He had a great sense of humor. It’s important to be that independent.

Hunter Braithwaite contributes to Ocean Drive, The Paris Review, and The Virginian-Pilot.