280 pages

When I was in sixth grade, my parents sent me to an elite private school in Boca Raton. My idol there was Erik Persoff, a senior who had the long curly hair of an outcast but was easy-going and friendly. He was by far the best musician in the school orchestra as well as the best artist. He was also the guitarist in a popular punk band he’d formed with some public school friends. I remember going to Peaches and seeing his band’s tape for sale at the counter, which blew my mind. The summer after he graduated, he was heading to the Berklee School of Music on a full-scholarship, but instead he died in a one-car accident in the middle of the night. Word on the street was that he was on LSD.

The next year, in choir class, I found a sketchbook underneath the wooden risers of the theatre seats. It was Erik’s. There were only four pages with drawings on them, plus the cover, which looked like a metal album. There was a nuclear mushroom cloud in the middle surrounded by a mélange of cartoon characters perfectly rendered. I took the sketchbook home and never told anyone about it. By myself, I’d look at the drawings and daydream about being a real artist, while also assuming that I would die young like Erik. I’d never met a real artist or musician in Boca, so I just assumed that Florida killed us all before we could make it out.

Paul Kwiatkowski’s illustrated novel And Every Day Was Overcast is a series of Erik Persoff stories. Here are bright kids who might have turned out fine in another state but are doomed by the fact that they were born here: two sisters who live behind a biker’s tavern, a kid obsessed with his transistor radio, the daughter of a single mom who believes her kids should do drugs at home “because it’s safer.” In Kwiatkowski’s Florida, “America’s Phantom Limb,” as he calls it, any kind of distinguishing characteristic is cause for concern, especially beauty. Being beautiful makes you susceptible to people like Trick, a 20-something drug dealer who preys on high school girls, or Hailey, a lonely single-mother who seduces boys. Love itself is carcinogenic: Trick’s behavior is “explained” as the result of the premature death of his beloved younger brother. A woman named Janet Jackson loses all her prized parakeets to a hurricane and disappears. After a romantic outing with a girl turns tragic, Kwiatkowski’s narrator, also named Paul, says, “At that moment, I knew that she truly hated me and rightfully so. I had marooned us on that small hell.”

That “small hell” could also be Loxahatchee, the small town west of West Palm Beach where Paul grows up. Loxahatchee is famous for being the home of Lion Country Safari, where all of us South Floridian children were forced to go. It was a drive-through zoo, which made the sad and malnourished animals who circled the car seem like homeless people at a traffic light. Even the smallest of us realized that this was not the jungle but the jungle’s unfortunate outcasts.

In South Florida, wealth is concentrated along the ocean and quickly dilutes as you go west, as if it were a tide that only washed so far to shore. By the time you get out to Loxahatchee, the dream of a Floridian paradise has turned into a swamp of trailer parks and single-family homes one paycheck away from sinking into the muck. This is the other South Florida, the one descended from John Ashley, the one that raised Albert Gonzalez and Mary Carey, the one that produces the priceless “Florida Man” and “Florida Woman” Twitter feeds. What rich parents like mine often find out only too late is that you can live by the ocean, send your kids to private school, and orchestrate their friends, but the rest of Florida still might get to them. I was as meek and sheltered as any kid in the history of Palm Beach County but I met plenty of people like the ones in Kwiatkowski’s photographs. If you wanted to drink or have sex or fall in love, it was unavoidable.

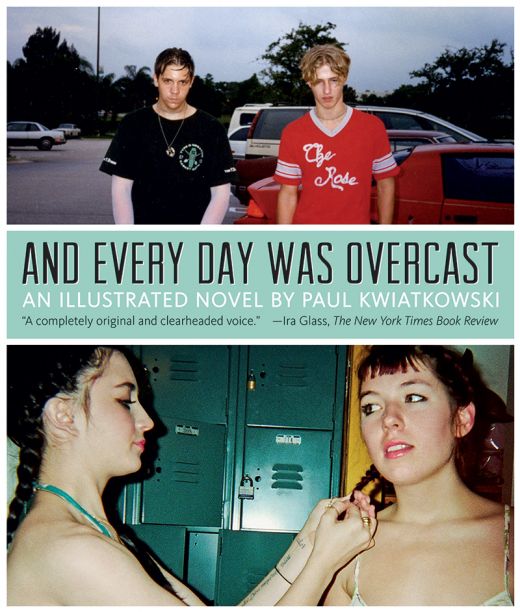

Kwiatkowski calls his book an “illustrated novel,” a piece of craft that he cleverly undercuts at almost every juncture. Like a movie that begins with the cryptic phrase, “Based on a true story,” each section of text is buffered by a series of pseudo-archival photographs that creates an aura of authenticity. A story about rabbits and cleared swamp is followed by pictures of a rabbit and a cleared swamp. A story about two sisters is preceded by a picture of two girls who look like sisters. None of it feels made up. The pictures seem like they came from a gigantic box in the back of Kwiatkowski’s closet. His bio says he’s a photographer, so in all likelihood, these are all his photographs. I’d be shocked then if I learned that not a single page of the book was invented. Which is the point.

Normally, people use the membrane of “fiction” to protect the innocent. Kwiatkowski does the opposite; he uses it to subvert his book’s authenticity. If this were a memoir, we’d start asking questions about the details and miss the point, which is not to show everyone the real story of growing up in South Florida, but to show what it feels like to grow up in South Florida. Memory, as Kwiatkowski knows, is a sham. Sometimes I think I made up every detail about Erik Persoff, but even if I did, it wouldn’t make the story any less accurate about how I grew up. Paul’s story is peppered with photos featuring one particular blonde boy who is his obvious stand-in. He’s never identified as such, but he doesn’t need to be. Whether it’s Kwiatkowski or not, doesn’t matter. That kid is Paul Kwiatkowski.

These kind of loose associations are the strength of the novel; the weaknesses are the connections. The book has the structure of a recurring joke: you know every single story is going to end badly, and you wait for it like a good punch line. What holds it all together is the tone, the humid air created by the prose and photographs. Kwiatkowski doesn’t need to bother with plot, but the hint of one sneaks in anyway. Cobain, a.k.a. Retard Radio, an outcast obsessed with his transistor radio, becomes a false spirit guide for Paul, who feels guilty for not helping Cobain at a crucial juncture in his life. No actual consequences stem from the incident. No character changes because of it. Cobain simply disappears from the novel and then hangs around on the periphery, but his character is treated as if he’s the key to Paul’s soul. It’s only the slice of a conventional device, but it sticks out like a sore thumb.

The recurring character I wish had gotten more screen time is Predator, the movie. One of Paul’s friends likes to tag buildings with the words “Val Verde,” which is the name of the fictional South/Central American country where Predator takes place. A fiction invented by Hollywood to avoid lawsuits, Val Verde is also the name of the country in another wonderful ‘80s Schwarzenegger movie, Commando, as well as being the homeland of Die Hard 2’s villain General Esperanto. It’s any place in Hollywood where bad Spanish is spoken, drugs are produced, and dictators reign. It is the opposite of the “Sunshine State,” a name invented to fool tourists into ignoring the constant thunderstorms. Val Verde swallows everything negative and racist about Central America and turns it into an overgrown jungle where alien assassins lurk and men with guns plot to rape and murder white people.

In other words, it’s almost as scary as Florida.