Facadism: “Who Goes There? Speak up or get a facelift!”

David Levi Strauss

A Deco Façade on Collins Avenue, October 2014.

David Levi Strauss came to Miami as part of the Visiting Writer Program, which is generously supported by the James S. and John L. Knight Foundation.

Since I was only there for three days in October, my impressions of Miami are bound to be superficial. But the more time I’ve had to reflect upon it after returning to New York, this glancing encounter with the surfaces of things may be more indicative than I first thought.

As the artist Nick Lobo told me over pisco sours at SuViche, Miami is a resort that grew, and grew some more, but it’s still a resort—a place where people come to get away from wherever and whatever they’re from, and whoever they were previously connected to, for a while or forever. The tourist hustle and the short con are as old as the sea and as new as that day’s sunlight. Visitors are welcomed, sized up, and fleeced in endlessly inventive ways that pepper the conversations of locals. Visitors who stay longer begin to welcome, size up, and fleece newcomers, in turn.

As a resort and a major port, Miami is a place where people and things arrive and move through, leaving traces, certainly, but nothing is built to last. If newcomers forget the other reason for this, they get a powerful educational reminder every year or so. Those high-rises in the Biscayne Wall surrounding the new museums, with names like New World Tower, Vizcayne, and Marquis, soon to be joined by a planned Zaha Hadid monstrosity called One Thousand Museum, look as insubstantial as concrete and steel structures can. They are the architectural equivalents of grasses and reeds, taking temporary root in the face of the inevitable tempest.

Rosângela Rennó, Waiting for…, 2014. Video Installation. Duration 64’14”. Photo: Oriol Tarridas. Courtesy of CIFO Art Foundation, Miami.

I liked the Pérez building right away, from its slatted roof and deck to the green columns connecting them—hanging gardens by French botanist Patrick Blanc—and the brass handles on the front doors. The steps overlooking Biscayne Bay are a far-sighted iconophile’s delight. Herzog and de Meuron designed a building that is in active dialogue with its surroundings, where the use of materials is carefully considered. It’s not Louis Kahn’s Kimbell, but it’s pretty good. Facadism is turned inside out here, so the facade is not a mask, but a porous scrim over a constantly changing interior, like the scrims Adler Guerrier echoes in his sculptures.

At the opposite end of the facadism spectrum is the Villa Vizcaya, that simulacrum of Old Miami, where every available surface is taken over the top, with filched and filigreed ornamentation from an imagined Old Country. It is a camp monument to the Gilded Age, complete with an elaborate cover story for the master of the house. But his lover Paul Chalfin’s painted, shell-encrusted ceiling and walls for the hidden grotto swimming pool makes the most outlandish examples of artifice and excess in Miami Beach look like they were made by Shakers.

The hundreds of fifteen-year-old Latina girls that come to Vizcaya every day to be professionally pimped, primped, and photographed in their finery and sexual bloom understand that what really matters is the surface of things, not what’s underneath. Show a good finish at the beginning, and no one who matters will pay much attention to what’s hidden inside, until it’s too late and all the papers are signed. The girls’ parents pay dearly for the use of the villa’s opulence as background for their daughters’ pubescent splendor. When they do, the Vizcaya museum gives each of them a free pass, to tour the mansion and view the treasures within, but none of them ever uses the free pass. They sell them on Ebay. As well they should. There will be plenty of time to admire and reflect on the beauty of things after one’s own fleeting beauty flies.

Miami made me think about fleeting beauty, and images as facades, and the importance of importation and movement across borders. Miami is hard to get a fix on because it’s like an open door. Everything is moving through. On the way to lunch, Nick Lobo told me that he prefers to eat pelagic fish, when possible, as opposed to fish that live on or near the bottom of the ocean, or reef fish. The latter are more localized, whiter, less substantial, and more prone to parasites and diseases. Pelagic fish, in general, are better tasting, he thought, probably because of the enzymes they produce. Nick surmised that pelagic fish produce these enzymes because they move around more, rather than hanging out in one place, as bottom feeders and reef fish do. They migrate across borders and are thus freer. And free tastes better.

Blue Fin Tuna. Photo credit: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Image courtesy of the Patricia and Phillip Frost Museum of Science.

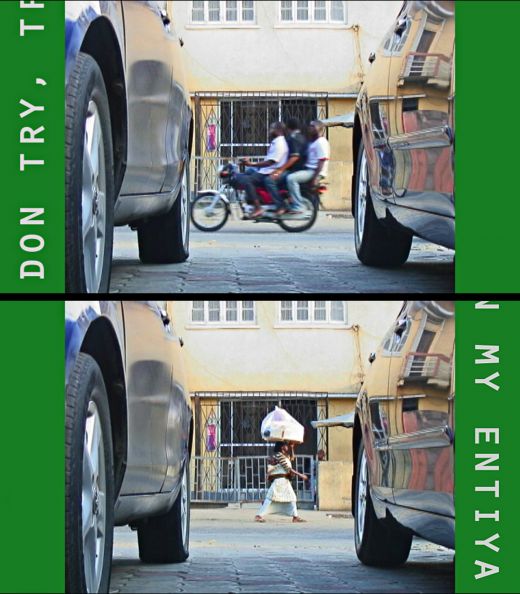

This particular relation to the surfaces of things, especially surfaces that are set up as facades, as screens, made me think about all the images I saw in Miami differently, but one work, in Fleeting Imaginaries, the 2014 Grants and Commissions exhibition at CIFO (Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation), was especially memorable. I knew a little about Rosângela Rennó’s work, and wrote about her images from an archive of glass slides of prison tattoos in Brazil in Words Not Spent Today Buy Smaller Images Tomorrow. I heard the work at CIFO before I saw it. Emanating from behind soft curtains came the sound of a duet of horns—a quite beautiful, if basic, composition. Inside the darkened room, one saw a projection of two cars, side by side, facing the viewer, having a conversation with their car horns. The conversation was in Morse code, translated in vertical bands scrolling up each side of the screen. The first message was a question and a command: “Who goes there? Speak up or get a face lift!” We are told that the two voices are intended to channel Fela Kuti and Tony Allen of Afrobeat fame. Between the two cars, one could see pedestrians and vehicles passing by on a street in Lagos, Nigeria. As the conversation between Gogo and Didi (Fela and Tony Allen) in Waiting for . . . continues and becomes more heated, life continues on the streets of Lagos. Taken together, this was an image of urban communication that made me stop and think about the current state of our communications environment in relation to images. As we become more and more screenal, is the image pulling away from its referent for good, and acting more like a facade than a window?

As we lifted off from Miami International Airport and flew north along the coast, the three layers of crowded shore, azure sea, and scumbled white clouds gradually pulled apart. The populated shore shrank, the clouds dissipated, and sea and sky joined to form one vast, undifferentiated mass.

Many thanks to Hunter Braithwaite and everyone else at the Miami Rail; the Knight Foundation; the Pérez Art Museum; May, Bea, and Billie at the Vagabond Hotel, for making me feel at home; Gina Wouters at Vizcaya, Silvia Barisione at the Wolfsonian, Daniel Clapp at the De La Cruz collection, and Kelly Martinez at CIFO; all the people who came to Locust Projects for their hospitality and conversation; Shabazz Napier and the Heat Lifers; and Jarrett Earnest’s mermaids.

David Levi Strauss is the author of Words Not Spent Today Buy Smaller Images Tomorrow (Aperture, 2014), From Head to Hand: Art and the Manual (Oxford, 2010), Between the Eyes: Essays on Photography & Politics, with an introduction by John Berger (Aperture, 2003, 2012), and Between Dog & Wolf: Essays on Art & Politics (Autonomedia, 1999, and in a new edition with a prolegomenon by Hakim Bey, 2010). He is Chair of the graduate program in Art Criticism & Writing at the School of Visual Arts in New York, where he also runs the Art Criticism & Writing Lecture Series.