- FROM POTTERY TO POPULATION DATA: The Diverse Influences of Adriana Varejão

- Martine Syms with Christy Gast

MĂIASTRA: A History of Romanian Sculpture in Twenty-Four Parts

Igor Gyalakuthy

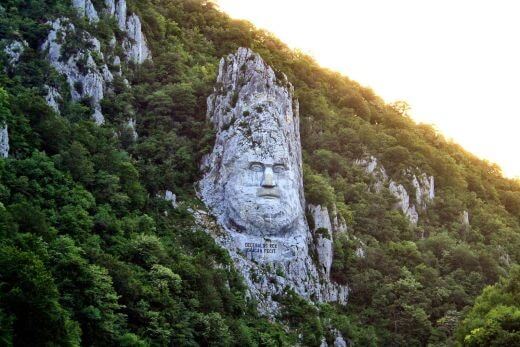

This is the gorge of the Iron Gates, where the blue Danube splits Romania from eastern Serbia. It was here across these waters that Emperor Trajan built the Bridge of Apollodoro. Trajan’s bridge, longest arch bridge in all of Europe, aided his army in conquering Dacia. This stretch of Danube is, or it once was, also home to the fortress isle of Ada Kaleh. [Note: more on the curious case of the water-logged smuggler’s den of Ada Kaleh on the way.] But the gorge’s most bizarre artifact has roots in neither the Roman nor Ottoman Empires.

Carved into limestone cliffs high above the river is the face of the last ruler of Dacia: Decebal, who died while defending his land from the greatest conquering empire of all time. The statue measures near forty-three meters high, the largest stone sculpture in all of Europe. Up close, the large face looks like something primeval, the relic of some lost civilization. Primitive and ancient though it may seem to be, Decebal is only eleven years old. Commissioned in 1994 by Iosif Constantin Dragan, it’s a modern marvel. The stone head, which took twelve sculptors ten years to carve, cost Dragan upwards of one million dollars. [Note: Decebal’s human head was cut from its trunk and tossed down the Gemonian flight of stairs in Rome.] Dragan made his billions exporting petrol to Italian fascisti in World War II. In his more advanced years, he turned his attention to the rich history of his own country. And with his Decebal monument, he sought to repay his nation with an ode to its past.

In Greek myth, the sirens were mantic nymphs who preyed on any seafarer who dared pass their coast. They sang odes with “honeyed voices” to the triumphs of the men in order to lure them to shore. Those Greeks who in weakness succumb to the sounds of flattery were seduced, murdered and gutted. Above the rocky shores of Istros, Dacian for the Danube, another siren’s song rings out.

—

Decebal has become a major icon of the pseudoscience of Protochronism: a brand of dubious cultural politics specific to modern-day Romania. It is revisionist history hewn from Dacology, the study of ancient Dacia. As a field of study, Dacology began with the works of Bogdan P. Hasdeu, bien sur. Hasdeu wrote verbose treatises about the non-Latin roots of Romanian culture. Ever the folklorist, Hasdeu “did not hesitate to infuse history, sometimes in defiance of the evidence, with the values in which he believed.”1 [Note: for more on our esteemed national alchemist and the sad tale of his daughter, see Part II.] Nonetheless, his theories soon became the tools with which Protochronists “helped to construct a fictive mono-ethnic cultural heritage from the political reality of a

multi-national state.”2 Romania, remember, is the old chimera, torn by war and bandaged by protean borders. My father, born in the Carpathians, in Brasov, then Austro-Hungary, was in fact Magyar. My mother’s hometown of Czernowitz is now in Ukraine, yet a Ukrainian she was not.

Origin stories of this country have always inspired more shame than pride in its people. It was this inferior feeling that spurred the Dacologists to try and alchemize the past. Dacia grew, in their minds, to be the spark that lit the flame of all human civilization. [Note: if this is beginning to sound like that other European pseudoscience, you have a good ear.] Rome, to them, was, in fact, colonized by Dacian immigrants, and not the other way around. The language of proto-Dacia was the basis for Latin, for all tongues, preceding Sumer. Even the Christian faith is heir to Zalmoxianism, religion of proto-Dacia. Fiction, it seems, is a valley lush with low-hung distinction, ripened and ready for the pluck. “Dacomania,” as its known, found a new life under the Ceausescu Communist regime. Ceausescu saw in Dacology a way in which to grow his cult of personality. He carved for himself a lineage leading back to the great Burebista, a Dacian ruler: “Burebista offered Ceausescu supreme legitimization, as the ancient king’s state prefigured in many ways (unitary, centralized, authoritarian, respected by the ‘others,’ etc.) his own Romania, as the dictator liked to imagine it.” 3

It is far easier to promise people a noble past than promise them a bright future. He filled his people with stories of heroic ancestors while he drained away their assets; while he razed sections of structural history to make way for new, ubiquitous bloc homes. Ceausescu’s reign ended after the Revolution, but Protochronism remained. A new band of protochronies rose from the ash, led by our wealthiest citizen: Dragan. During Dej’s Communism, Dragan had been exiled for his ties to the old Iron Guard fascists. But Dragan found foothold in Mr. Ceausescu’s regime, and profited off of its ethos. The sculpture opened to the public in 2004, and inscribed below it, the words: DECEBALUS REX DRAGAN FECIT— King Decebal, Made By Dragan. The piece is, as he wrote, “aimed at reminding Romanians over time how great and glorious their past had been, what were their place and role in world history, and what was the basis of the nation’s present and future.”4 Decebal was to be Dragan’s Mount Rushmore, and parallels drawn between the two are quite apt. Both attempt to whitewash the extant histories of their lands with chisel, dynamite and axe: Rushmore was carved from Six Grandfathers mountain in Dakota, robbed from the Lakota Sioux tribe; Decebal’s monument was built to rewrite the conquest of Dacia by the Roman Empire. [Note: and both of these regions, in response, gave the men who would scar their faces a hell of a time.]

—

On myth and mischief in the world of Romanian cultural politics, Boia put it best: “Michael the Brave did indeed unite the Romanians, not in 1600, but posthumously in 1918.”5 But the true genius of this mawkish siren’s song lies not in its message but in its matter. Stone is a guileless material, one we chose for its strength rather than its grace or beauty. We use stone so that the physical memories of our fathers will outlive our sons. Wood is a substance so mortal and composite, vital and rare it is utterly human. But wood splits and burns and so fails to conquer our childlike fear of death and immortal striving. And like wood, humans are delicate, betrayed by time and our decaying natural bodies. Even now, as I write, I can hear my aged voice grown hoarse from shouting: “Race straight past that coast! Soften some beeswax and stop your shipmates’ ears so none can hear.”6 As I shout, the stone face of this gargantuan monument takes on the patina time brings. The false past he denotes appears more authentic to each new generation that sails by him. As an art historian concerned with memorial sculpture, this idea sends chills through my spine. This country simply can’t afford to look away from the truth of its past, not for one moment.

Yet there is one thought that consoles me, one small hope to wish for, though I may well be dead by then. During its construction, the sculptors ran into problems with Decebal’s enormous rock nose. Noses have always been, at this scale, famously delicate; just ask the Great Sphinx of Giza. Though they share similar densities, limestone lacks the compressed strength of Mt. Rushmore’s tough granite. Finding the limestone too porous to hold the nose, the sculptors patched it with concrete and rebar. This technique of sculpting, while surely practical, is dodgy and not quite archival, really. The concrete adds pressure to the stone, creating hairline cracks into which foul weather can seep. One day the gigantic nose of our Dacian king will sheer off, collapsing into the river. In murky brown waters, we’ll find it, sunk like the relics of Trajan’s Bridge and Ada Kaleh. Then the King Decebal, noseless, will be transformed forever, more of a sphinx than a siren. And those who pass through the Iron Gates of Istros will hear not answers but questions in their ears.

(see PART I: WANDERING ROCKS, PART II: THE CHIMERA, and PART III: PROTEUS)

Dr. Igor Gyalakuthy is a professor emeritus at the Universitatea Nationala de Arte in Bucharest. In 1993, he received the national medal for achievement in the field of art history. He lives in Cluj- Napoca with his Lakeland terrier Bausa.

—

1 Lucian Boia, Istorie şi mit în conştiinţa românească (Bucharest: Humanitas, 1997), 26.

2 Katherine Verdery, National Ideology under Socialism. Identity and Cultural Politics in Ceaușescu’s Romania (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 1991), 206.

3 Boia, Istorie şi mit în conştiinţa românească, 52.

4 See www.decebalusrex.ro/en/history-of-the-monument.

5 Boia, Istorie şi mit în conştiinţa românească, xxx.

6 Homer, The Odyssey, trans. Robert Fagles (New York: Penguin Books, 1996), 198.