Barnacles on the Boat: Notions of Literature at the Key West Literary Seminar

Mark Hedden

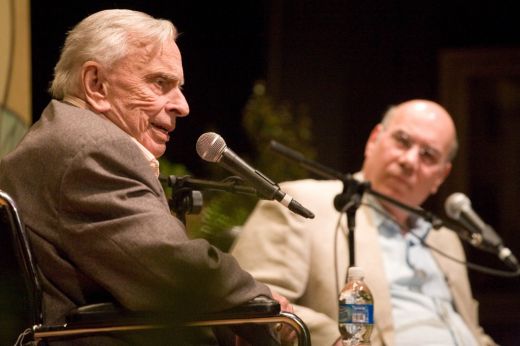

Gore Vidal in Key West, 2009.

Which might make him sound like some kind of Norris/Stallone/Lundgren-style fighting machine. But he tries to talk his way out of bad situations when he can. And he also knows the right time not to punch or shoot someone, and when to get beat up a little bit, maybe kidnapped and thrown into the back of a van, or handcuffed to a radiator next a ticking abomb. Because sometimes it’s not the right time to punch or shoot someone. Sometimes you have to be patient and wait for the world’s pressure points to reveal themselves.

There is a certain straightforward handsomeness to a Jack Reacher novel. As with kabuki theater and opera, it’s all about the grammar of it, the overt plot mechanics, the narrative flow, and how well it all comes together. The strength of a Jack Reacher novel is not guessing how it will turn out in the end.

I suppose this could be the place for an obligatory digression into the whole hand-wringing yeah-but-is-it-literature issue, but Elmore Leonard said it best: Don’t write what you don’t want to read. Also, having seen Lee Child onstage at the Key West Literary Seminar (KWLS) this year, it feels like the question is moot. The KWLS is always a mixed bag, though it’s usually a high-quality mixture. This year was its 32nd year and the theme was “The Dark Side: Mystery, Crime and the Literary Thriller.” It might have been the most commercial theme, or at least the most best seller-ish, to date.

Child has written 18 Jack Reacher novels and sold about 50 million. (Actual number.)

Child’s talk “The Prehistoric Roots of Storytelling” started out simply enough, with a seemingly casual riff on people who knew how to tell stories, and people who didn’t. Bad storytellers, in his view, weight their narratives with too much tedious detail, miring them when they need to move forward.

While joking about this, he rewound things back to the time of earth’s molten core cooling. Then he started bringing it forward. In about 10 minutes he made a strong, cogent case—a charming argument—for the biological and evolutionary necessity for the adventure story in general and the thriller in particular.

Essentially, when humans took up storytelling, about a thousand millennia ago, there was not much room in their habit or psyche to do things that did not enhance their chance of survival. So they told thriller stories.

“Somebody in dire circumstances solved his problem and everybody who hears that story feels a little bit better, feels just a little bit stronger. Feels that yeah, maybe they could do that too. And it made them slightly more likely to be alive next week.”

He took issue with the latter-day notion that thriller fiction was a lesser genre than literary fiction.

“That is completely ass-backwards. Thriller fiction is the genre. For the best part of 100,000 years it was the only genre,” he said.

“All these eons later, we are fat and happy and safe, and so these other genres have grown up alongside us. To which I say: you are like a barnacle on our boat.”

“You want to write about your [mean] mom on the Upper West Side, go for it. But don’t tell me that that’s something more integral to the human experience, or somehow more important, than those stories about facing desperate peril and surviving it,” said Child.

It reads more prickly in print than it sounded coming from the tall, affable Englishman in the rumpled sport coat standing at the lectern, but it was an object lesson in elemental storytelling, a low key tour de force. Having successfully Jack Reacher-ed the concept of high literature, he thoughtfully answered questions from the audience, then sat down in the bullpen with the rest of the writers and listened to the next speaker. Child’s talk was one of the unexpected great things at this year’s seminar. Another one was Alexander McCall Smith, who I’d been cynically and unfairly blowing off for years as a twee sentimentalist who wrote condescending tea cozies about people in Africa, but who turns out to be a thoughtful, archly funny gentleman who is pretty deeply in love with his characters, and the people who inspire them, and possibly the rest of the world.

Thinking about it, “unexpected great things” might not be a fully accurate phrase. You usually hear a couple great things at every year’s seminar. It’s why you go. But you never know where it’s going to come from. Some really good writers are great on the stage, some aren’t. Some writers you’ve never read before knock your flip-flops off.

A KEY WEST LITERARY SEMINAR SESSION is usually a long weekend, starting with a keynote on Thursday night, and finishing in time for lunch on Sunday. (Sunday afternoon is usually a free session, in which locals and paying attendees have the chance to get in on a first-come, first-seated basis, and the line for entry usually stretches down the block.)

Some years they do one session, some years two sessions on consecutive weekends. It depends on how popular the theme is.

The KWLS is similar to the Miami Book Fair in that it attracts a lot of high-wattage writers. With about two dozen writers per session, the Key West event is smaller than the seemingly-infinite Miami event. At Book Fair, the writers usually have one fifteen to forty-five minute session on stage. At the seminar they tend to go up three or four times over the weekend, and you get to know the writers. Or at least feel you do.

One other difference: the book fair costs less than $10, and the entry price for a weekend at the KWLS this year was $575, though that does include breakfasts, several dinners, several open bars, and the chance at actual conversation with many of the writers.

For the last decade and a half, the KWLS has taken place at the San Carlos Institute, a large, Spanish colonial, 370-seat hall on Duval Street. The high-arched building looks like it came straight out of Havana, except the building has been maintained and has central air conditioning. Since the San Carlos is considered the “birthplace of Cuban liberty”—Jose Martí made an important speech there in 1892—the Cuban national anthem is played before the keynote every year, after the American national anthem, something that tends to mystify people from the northlands.

While the first seminars were held in the more modest auditorium at the Key West Library, they have always had a respectable roster of writers. In 1991, the first year I lived in Key West, the big name on the poster was Kurt Vonnegut. And while he ended up canceling due to health issues, I remember walking around town and thinking, wow, I have moved to a place where Kurt Vonnegut could show up at any minute.

A semi-random sampling of early notable speakers includes: Elmore Leonard, Jane Smiley, Jim Harrison, Mary Higgins Clark, Tim O’Brien, George Plimpton, Lanford Wilson, James Leo Herlihy, Bobbie Ann Mason, and Stetson Kennedy. Which gets you up to 1991. Current and sometimes local residents, such as Annie Dillard, Robert Stone, Joy Williams, Tom McGuane, Alison Lurie, and Judy Blume, have all appeared multiple times.

Two-time U.S. poet laureate Billy Collins has been part of every seminar but one since 2003. He’s become sort of the house band, or at least the house poet, giving short readings and sitting in on the occasional panel. Most years he can match something from his oeuvre to the theme. This year, with the subject being crime, he had to punt a little, reading poems about the urge to drown children playing Marco Polo in a pool (because the narrator had a hangover) and about a dog’s letter to his former owner, telling the former owner he never loved him, that their whole relationship was a lie. (“I don’t do dark very well, I don’t do crime. But I can do creepy, and I can do freaky,” Collins said on stage of the San Carlos.)

I could go on, but that would just be list-making, and the point of the seminar isn’t fawning over literary eminences, though a bit of that goes on. The point is to watch and listen to what happens during the recombinant panel conversations and talks—the way things, over a weekend, can eddy and loop together and gain resonance in a largely organic manner.

Sometimes writer responses are pat or rote, but often you get to see some of the smartest and most articulate people in the world thinking, right in front you. Maybe not lightning in a bottle, but thunder.

Things I have seen, heard, and appreciated in recent years:

Geoff Dyer trying to explain the critical and narrative motivations to his thought processes in a way that mere mortals can understand.

Junot Diaz, when he only had a book of short stories out, sprinkling F-bombs like holy water.

Andrea Barrett talking about her research process. Because Andrea Barrett is compelling enough to stand there and talk about research and have you hang on her every word.

The cool-eyed Margaret Atwood’s slow, gentle dismemberment of another, more self-indulgent panelist, who had gotten a bit shirty with her.

Calvin Trillin and Roy Blount, Jr., sitting back in chairs, and cracking wise for a solid hour about the pleasures and nuances of food and the great American dining experience.

Janna Levin, a theoretical physicist/novelist, talking about the tragic lives of Alan Turing and Kurt Gödel, and also about her doctoral thesis, titled “Is The Universe Infinite Or Is It Just Really Big?”

Kevin Young slaying with food poems like “Ode to Pork.”

William Gibson, slumped in a chair, seemingly tuned out, then throwing out the occasional devastating one-liner. (He was at the seminar for the second time this year. Best line: “Whenever I hear the phrase ‘restoration of order’ I think something pretty bad is about to happen to a lot of people.”)

People who were there speak rhapsodically about the seminar that focused on the works of Elizabeth Bishop, who lived in Key West in the 1930s and ’40s. It wasn’t the most star-studded seminar, but people like Octavio Paz and James Merrill, as well as others who knew her, spent several days discussing the life and work of a poet who was not rightfully appreciated when she was alive.

Panels don’t always work. Writers occasionally fall flat or offer up ideas or anecdotes that don’t gel. Panelists sometimes decline to engage with one another, or try but fail to mesh. There is the occasional villain. The cookbook editor who told the audience, without irony, that they couldn’t understand anything about food unless they’d cooked with a set of $400 knives. The moderator who talked over the moderated to tell tedious tales of her lineage. The moderator who kept asking a group of steampunk writers “But what is steampunk?” even though they’d already answered the question three times.

Gore Vidal came in 2009 and behaved pretty horribly towards anyone who tried to talk to him. But it’s arguable, in the rifle-on-the-wall sense, that having him behave horribly was the main point of inviting Gore Vidal anywhere. There hasn’t been a villain at the seminar for a few years, though one male writer skated close this January when he described writing a rape scene as largely “an engineering problem.” Honestly, I kind of miss the villains. They serve as a unifying force, bonding the audience and helping solidify what people think about certain subjects.

WHEN LEE CHILD WAS ANSWERING QUESTIONS after his prehistoric roots of storytelling talk, he threw out the line that “there are really only two types of books: those that make you miss your stop on the subway, and those that don’t.”

It was a nice bit, a workaround for the whole “Is genre writing literature?” question, and a way to move forward. It was also a reworking of the great Oscar Wilde line—“There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all,”—and a reminder that the best literary arguments are never settled quickly. Thinking about it, some of the best things I’ve seen at the KWLS have happened during years when people question the notion of what literature is, where its boundaries are, and if those boundaries even exist. The conversation has happened, in different forms, during years when the subject was science writing, historical fiction, food writing, science fiction, children’s literature, nature writing, and travel writing. And probably on other years.

One of the last panel discussions at the first session this year took place between Laura Lippman, Megan Abbott, and Gillian Flynn. Lippman has written twenty books, including a series featuring Tess Monaghan, a Baltimore P.I., and at least one novel about an upper middle class madam. Abbot has written several thrillers about teenage girls that are as compelling as they are disturbing and discomfiting. Gillian Flynn wrote Gone Girl, a well-crafted intrigue about a morally questionable couple in the midwest which has sold insanely well and is the basis for a movie coming out this fall starring Ben Affleck and Rosamund Pike.

The official title for the panel was “Fatal Vision: The Imprint of True-Crime Movies”, but basically it was three funny, passionate women of serious mind and ability making the case that Lifetime movies deserve far more credit than they get. That they are often based on some pretty solid books, and are well crafted, and give meaty roles to actresses who have aged out of the basic Hollywood demographic. That they are often dismissed because they are domestic stories, and focus on women, and that people’s notions of art and craft are sometimes more the product of production values and prestige than the quality of the work.

It was one of those great, electric conversations, sparks and jokes and insights flying around the room, the smell of ozone almost palpable. Afterwards, you knew it had pushed a few boundaries. Yes, it was a great conversation, some people said. But was it literature?