Daniel Milewski: The Umpire

Hunter Braithwaite

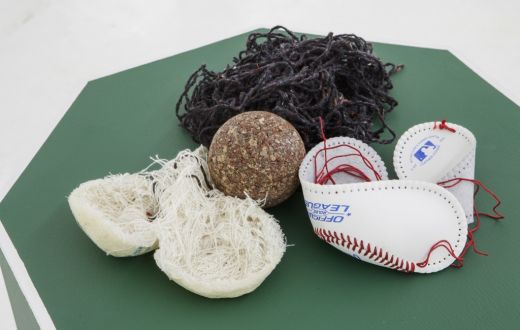

Daniel Milewski, The Umpire, 2012, Cork, wool, yarn, leather, wood, paint, 15.5 x 15.5 x 37.5 inches. Photo courtesy of Gallery Diet.

January 8, 2013-February 16, 2013

For his new show, Daniel Milewski takes the down-home objecthood of Americana and launches it into the nebulousness of pop cultural trivia, art historical references, and the artist’s own sentimental education. If there was ever a time to imagine some kind of union between Ted Nugent and Sophie Calle, as filmed by Cameron Crowe, it would be now.

Take “Gram” (all works 2012), a 7” cube of compressed ash resting upon a simple birch platform. The entropy, the unadorned geometry, and even the metric title all point directly back to Minimalism, specifically to the floor works of Robert Smithson and Carl Andre. But! If you remember that Gram Parsons spelled his name like so, and you remember how, after he fatally overdosed on morphine, his friends stole his body from LAX and attempted to immolate it in Joshua Tree, the piece takes on different meaning. It’s backstories like this that make The Umpire a good time, but the risk is always that the story outlasts the piece. This problem is read in the titular piece, a baseball eviscerated on a green octagon. Milewski has yanked out the stitching from the ball, removing the yarn and cork center. There’s no way to put the baseball back together; all which was contained is now out in the open, and it will not fit in again.

Milewski, who studied at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, is adept at first creating narratives out of communal and personal experiences, and then complicating them. This is where the exhibition title’s sports allusion comes in. There are the rules of the game, and then there is how it’s actually played. Visually, the show relies on a tension between continual revision, seen in pieces serial in nature, and the grand gestures of minimalism. The artist brings the levels of form and content together by examining how a seemingly indifferent material such as wood turns out to be, well, different in the various cultural contexts in which it appears.

In the back room is “Nationalism,” a truncated log with said word gouged into it. Tongue pressing Red Man into cheek, the piece first hollers some backcountry manifest destiny Bunyanism, but then rests in the ash of “Gram,” although not before moving through the Dionysian “Double Fantasy” which has two shirts draped on the top of two 2×4 studs. The shirts, one parrothead and the other deadhead, look like wilted sunflowers, and the wooden stems speak not only to building a national identity, but to the often generic fill-in-the-blank of cultural loyalties.

The apex is the bathetic “Everything Wrong with the House.” In the shade of the best serialists of the twentieth century—the Bechers, of course, but also Ruscha’s “Every Building on the Sunset Strip”—Milewski presents grid of banal photographs detailing the problems, both cosmetic and structural, of his home. The wood is dry-rotted, but the house still stands. By presenting the single-family home as citadel beat down by time and weather, Milewski again conflates the personal with the epic, with humorous effect. This imbues The Umpire with gentle irony, one that does not completely disassemble our communal experiences, but renders them personal.