Human, So Human / Illusionist, So, Illusionist

Hunter Braithwaite

Installation view of Angela Valella's "Human, So Human."

Marcos Valella

February 5 – March 30, 2014

A question we should probably ask ourselves in this community is “what is art for?” Can it do more than generate tourist dollars, gentrify neighborhoods, and validate socialites? Is asking anything at all asking too much? Could art be considered therapeutic? If so, what are its consolations? What about as a pedagogical tool? Ok, well what does it teach us? Hidden in a nondescript compound of art and novacaine run by orthodontist Arturo Mosquera, the context and content of two exhibitions allows the viewer to consider what art can and cannot do.

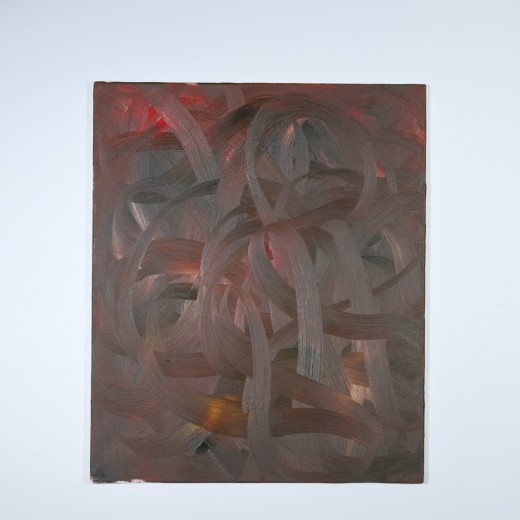

Respectively, Human, So Human and Illusionist, So, Illusionist are exhibitions by Angela Valella and her son Marcos. Her title riffs off Nietzsche; his, hers. Inside the placid waiting room, which is kind of a project space for the main gallery next door, Marcos installed seven paintings on the peach walls. The two closest to the door are endless swirls of colored ballpoint pin with dabs of paint coagulating in some of the formed negative space. The gestures of the lines connect to the other five, which use a sullied palate and the same hypnotic gesture. The paintings are controlled, on autopilot. They feel automatic. One imagines Valella’s wrist rotating more than they imagine his mind at work. The painter has tried to distance himself. His choices don’t make paintings, but they do. This waiting room isn’t a gallery, but it is.

One of Marcos’ Paintings

Next door, in a house converted to a gallery, Angela Valella presents two installations. The first is an impressive contraption made out of a table, two projectors, two sources of sound, and several different levels of a colored plexiglass. From the front of the gallery, the viewer sees a ghostly projection of dark rectangles arranging themselves on the sculptural screen. Modernist shards of Schoenberg come from a speaker somewhere, as do recorded growls from the early modern city. As the viewer walks around the tableau, they see that the other projector, facing the other way, emits an image of black pigment floating in white liquid. At once, the piece is a lecture about the relationship between twentieth-century art and the city, a sculptural cinemascape, and a poem about the creative cycle.

Angela Valella, It’s better to be an art work. Two wooden tables, lamp with tripod, group of collages, Dimensions Variable. 2014