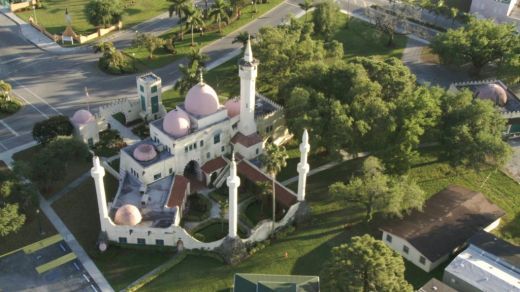

The minarets and domes of the historic Opa-locka City Hall. Photo courtesy: OLCDC.

Today, these stories intersect as the names of streets in Opa-locka, a municipality in northeast Miami-Dade founded by aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss. Curtiss retired (sort of) and moved to Florida where he fashioned the city inspired by the “Arabian fantasy” in what was then farmland. Ali Baba Avenue crisscrosses Sinbad Avenue around the corner from Aladdin and Sesame Streets. Marketers shortened the Seminole name of the area, Opa-tisha-wocka-locka, to an appellation heard as vaguely eastern sounding to those buying and selling exotic make-believe. Similarly concerned that prospects crossing Scheherazade Street might stumble over too many letters, they convinced Curtiss to name it Sharazad Blvd. Curtiss had sent the illustrated book, One Thousand and One Nights, to his genie Bernhardt E. Muller who designed the “Persian” palace that is the now the emptied historic City Hall, as well as an additional 104 structures, including the Opa-locka rail station, commercial buildings and private homes. The domes, patterned tile, minarets, keyhole archways and window frames in the city center compose the boasted largest collection of Moorish Revival architecture in the Western Hemisphere.

Scheherazade may have survived through her art; her transformative abilities softened the sultan, who made her queen, and the book remains sought by those who wish to be transported, but the “Baghdad of Dade County” it inspired has for been stuck for some time.

Today no chamber of commerce would choose Baghdad as an aspirational sister city, given its standing in the American popular imagination, but for the last four decades Opa-locka’s reputation too has become that of a war zone to be contained and forgotten. Many lives have been cut short in the Triangle, a crime-ridden neighborhood on the eastern border, just outside of the historic city center. In 1987, the city placed metal barricades blocking the streets of the Triangle in an attempt to quell, or cordon off, massive violence spurred by drug trafficking, the only steady cash flow through the nine-block neighborhood. In 2004, Opa-locka had the highest violent crime rate in the nation. Even if now decreased, it remains one of the highest rated cities for crime in the state.

“I’ve seen it go from good, better, bad, to where we are now,” says lifelong resident and crime watch commu- nity leader Johnnie Mae Green. Green has never left despite the hard times because, “Opa-locka has potential and

I know it.” The city removed barriers from the Triangle last year and the neighborhood was renamed “Magnolia North,” launching the first visible change in an NEA seed-funded plan to transform Opa-locka through art-infused public spaces including the City Hall. Coupled with other funding such as a Knight Arts Challenge Grant, this initiative is part of the larger ongoing work of the Opa-locka Community Development Corporation (OLCDC), a non- profit organization that primarily focuses on affordable housing and revitalizing economic conditions.

The Baghdad of Dade County. Photo courtesy: OLCDC.

“I was probably 13 or so before I could legally come to the other side of the city. From a perspective of someone who grew up here, and my friends, and my parents, we never saw anything attractive about it. It was theirs,” referring to the white population of the city.

Completed in 1926 and battered by a mega-hurricane the same year, the distinctive, yet fragile buildings in Opa-locka have remained in various states of neglect and disrepair since the land boom proved mirage. Taking a dramatic turn for the worst, the city declined in the ‘70s when the tax base disappeared with white flight, leaving no infrastructure for basic resources and little opportunity for its inhabitants—today a majority of black families who are below or at the poverty line.

In 1980, the 23-year-old Logan became the youngest mayor of Opa-locka, and of any U.S. city. Many local civic leaders told him that these buildings could be the key to the city’s revitalization. He looks back at the early 1980s and says, “to be honest I really didn’t get it, but we did put them on the National Register. We knew it was unique but it wasn’t really meaningful to me.”

He likens his former disaffection to a similar reaction he had going to museums and seeing centuries old European paintings and feeling a total disconnect, “I didn’t care about ‘Oh, but the light’…as an African American it is hard to relate to that [art]…It brings back those notions of colonialism, racism, segregation, lack of access. You didn’t get excited about it.” As he speaks, the distinction across continents and centuries narrows. Whether old paintings, or the fantasyland of Opa-locka, these are other people’s imaginings.

Curiosity surrounding the approximation of Moorish architecture fabricated in Florida limestone is one of the few reasons people visit Opa-locka. But the reality—a city of people who inherited someone else’s ruined whims of exotic fancy—does not stir the sublime. It’s not the place for tourists to indulge in extravagance, nor the sweet melancholic ache at the sight of devastated hubris that those with means may find in the remains of an extinct, crumbled oversees empire. Here the real estate evokes abandoned folly and lost futures, the schemes of early developers, at times conjuring amusement in the ruin of a fake. There is sadness. It is sometimes surreal, but far from Romantic.

Essayist William Hazlitt, moved by a sundial while touring Venice in 1827, likely visiting the Doge’s Palace arcades of Moorish Byzantine splendor, concluded that though it would be nice to count “only the serene moments,” to do so is to be wafted “into the region of pure and blissful abstraction.”

Under the archway and in the often-overgrown courtyard garden of the former Opa-locka City Hall, outside windows that frame overturned furniture and scattered papers, at the foot of an exterior stairway that leads to nothing sits a sundial without a gnomon to mark the earth’s spin. Broken, or perhaps intentionally made without the neces- sary part, the clock’s inscribed promise to “only count sunny hours” puzzles with its blind optimism or irony. A face in full shade or glare resists a rapt meditation akin to Hazlitt’s musings on the fragile mechanics of clocks and hour glasses in accounting for mortality. Even if a tourist could be awe-struck by an apathetic universe bigger than one’s small self standing in this courtyard, to do so would be to ignore the specificity of the context to contend with here, and to drive away moved, yet unmoved to consider one’s own potential role. But that is the common part played by a tourist.

While Hazlitt acknowledges that his preference for not count- ing was “a sign I have little to do,” many of Opa-locka’s residents seem to have little to take stock of in their faux-Moorish surroundings, not for the vocational lifestyle of a writer, but for lack of any available industry. If not a site for escapism, the heritage architecture begs for imagination to be put to use in seeing how it could work to improve the lives of the people who live there. One proposal beginning to be enacted brings outsiders, namely artists, to see the city in a new light. For those born and raised in Opa-locka, connecting with an aesthetic that is so aggressively unique it cannot be ignored, yet has offered little use-value, takes some consideration, and time.

It was not until many years after his life in political office, taking inventory of the scant resources in Opa-locka, that Logan became interested in revival architecture. The OLCDC is housed in the Harry Hurt Building, a former commercial building that is listed in the Historic Registry. Under the dome, a bookshelf in Logan’s office holds several volumes on Orientalist and Moorish art and architecture. Logan explains his own conversion with regards to the buildings, claiming, “it has a lot more significant meaning, to think it is from a region that I originated from, people who looked like me and something I can identify with, as opposed to a movie or a fairytale. Even though I don’t have a background in design, or architecture, I began to understand it. The way people perceive [the architecture] from the art.” Logan said for residents, just hearing outsiders speak with great interest in the architecture has made them positively reconsider their city.

Curtiss’s employment of an interchangeably Persian-Moorish-Arabic-fictional exotic to sell homes to white middle-class families may be replaced with a narrative of identification that in some ways is no more easily traced for Opa-locka’s current community. More importantly, Logan says, “One way to make the buildings meaningful is to make them into tangible benefits to the residents—economically.”

For OLCDC, part of imagining an Opa-locka with pride of place, resources, and businesses is attracting working artists to the city as part of its beautification and renewal. This may seem like a tired gentrification technique, particularly in Miami, where countless neighborhoods such as Wynwood and South Beach before it have pushed out locals in favor of artists who bring with them the wealthy in search of cachet. Often nomadic, artists who need cheap space are continually pushed from place to place by rising rents once they’ve made an area attractive. But Logan isn’t interested in that model for Opa-locka. “We want to learn from Wynwood and the Design District, we don’t want to be Wynwood and the Design District.”

It’s questionable whether comparable gentrification in that location would be successful, but even so, as a non-profit that does not deal with market-rate housing, it’s not even a feasible plan for the OLCDC. Gentri- fication is also hampered by 20-40 year deed restrictions on homes that can only be occupied by working families. Logan is interested in defining some of those working families as artists who are in the qualifying income bracket (up to $100,000 per year, depending on family size) and is considering setting aside homes in the development for artists who would have studio space in Opa-locka.

So practical questions arise. Of what use is Opa-Locka to artists and of what use are artists to Opa-locka? Aside from the intriguing architecture, why would artists want to work in Opa-locka if they can find cheap rents in other areas and why, if not helping to improve market values, is Opa-locka interested in artists?

The artists involved in bettering public spaces through the NEA-funded commissions have a chance to make funded work engaging with both a public space and an underdeveloped community. Others, like Carlos Betancourt and Albert Latorre, who share a studio in the historic district, have found a place to work that those just passing through may not experience. Betancourt explains that he has a space “with an ideal location…with no traffic and for the most part pretty quiet and peaceful.” It is, according to him, “very conducive for silence and creativity.”

Portrait of Reverend Taylor by Hunter Barnes.

Logan believes artists are a group he can bring to diversify the city. “Who am I going to get to come who’s educated, creative and going to take a chance at living and working in Opa-locka? It’s an ideal group of people who can come, willing to bring about change, diversity… I’m not going to go to Wells Fargo and talk to their executives, one of those kids who are interested in the high rises, the view, the fancy car, the access to the pool because its about keeping up with the Joneses and making money versus making a contribution.”

With diversity, Logan hopes to change the city’s reputation, so that as access to education and training for employment and business opportunities for residents develop through other efforts (recent mix-used zoning approvals, for example), people will begin to visit and invest in Opa-locka, not only for its architecture. While it sounds similar to gentrification, Logan says it is “for a noble cause.”

“Artists seem to get along with any and everybody. Though they may have opinions and judgments, it doesn’t get in the way of pursuing their life, vision, and goals which often times are as much civic and social as it is about creating stuff. They have a vision and passion that is much more than a piece of art. It’s a message; it’s about understanding, activating, motivating, and getting people to think.”

But artists are not a subset of human that equals noble. They are people, and many take risks in terms of moving to a place with a bad reputation just to buy more time to continue a practice that is economically uncertain, or if certain, not feasible anywhere else. Artistic survival and desperate measures alone do not make for meaningful, sustainable, transformation. The general consensus among those who have visited is that they’d like to see Opa-locka work. Some say they need to see more opportunities to see how it work for them, for example, to be granted ownership of free or cheap space that they would not be kicked out from after investing in renovations. As Scheherazade found safety through her stories, place-making initiatives suggest that art may be a rescuing force beyond a Miami real estate amusement. If accepted, how and whose stories are put to use, and to what purpose beyond the matters of saving one’s head, are questions that remain unanswered. These questions require more than artists to answer and entail new narratives, beyond Opa-locka’s headlines, not just told by outsiders, but from within the city’s quiet facades.