ETHERIZED UPON A TABLE

Hunter Braithwaite

Pierre Huyghe, “Untitled,” 2011-2012. Alive entities and inanimate things, made and not made,dimensions and duration variable. Photo: Nils Klinger

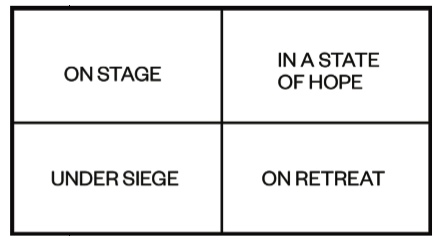

I bring up the comparison of skies because while Bavaria’s oscillates rhythmically between cloud and no cloud, Kassel’s contains both and neither at the same time. It is a city both pilloried to history and, thanks to Allied bombers, banished architecturally to the doldrums of post-war architecture. As die documenta-stadt, it represents a conflation of the stage and performance (permanence, temporality). Binaries fray. Taking advantage of this curious environment, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s dOCUMENTA (13) is organized around four broad trends that are best displayed visually:

Ours is a period of dislocation. Not of absence, not of presence, but a period of time characterized by the dull sucking thwohk of a ball joint being pulled from its socket. It is in the vacant space that trauma has opened up that we can function. We are in excruciating pain, sure, but the dislocating moment is one of supreme flexibility.

In the current world of artistic production, the flexibility provided by post-Fordist labor structures, cheap flight and plentiful biennials, and bespoke graduate programs is met with the rheumatoidal jam of austerity movements, thankless freelance gigs, and skepticism. We cannot support ourselves. I don’t merely mean this in a financial sense; I mean that the scaffolding that holds up our ontological circus tents buckled and we came crashing down. Intellectual laborers—the artist, the writer, the curator, the teacher—must reinvent themselves. Roles are converging. However, we cannot imagine this as a static, ahistorical situation. We need to think of converging, not convergence. And we need to accept that the forces that brought everything together are just as quickly pulling it apart.

One of this documenta’s foundational ideas is the myopia of anthropocentrism. In her words, Christov-Bakargiev’s documenta tried “not to put human thought hierarchically above the ability of other species and things to think or produce knowledge…” because doing so “…gives us a special perspective onto our own thinking. It makes us more humble, able to see the partiality of human agency…”

The show tries, and succeeds, to stretch the biped visitor’s conception of history, life, and knowledge. Parodoxically, this often happens best through a lens vaselined with humanist romance. In Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller’s piece, “Alter Bahnhof Video Walk” (2012), the viewer borrows an iPod Touch and goes on an artist-led video tour through the Kassel train station. The viewer does not navigate with their eyes; rather, since their progression through the train station is synchronized with the artists’ recording, they get around by looking at the screen of their device. There is a chasm between the recorded reality and that lived upon viewing the piece, but it is very small. Train stations tend to look the same. The piece is a startling critique of personal and public histories—the Alter Bahnhof was the point of departure for Jews leaving for Terezin and Auschwitz—but it also reaches into the future to a point where memory will be just another prosthesis.

Another piece invested in presenting a cinematic version of existence was Pierre Huyghe’s “Untitled” (2011-2012), in which the French artist turned the Karlsaue park compost heap into an amphitheater. There was a mutual distrust between environment and viewer as one progressed to the center stage, where a guard dog named Human (with one leg painted pink) paced around a reclining classical figure whose face was obscured by a beehive. Huyghe’s piece spoke to the viewer from a location far removed from the chronological and cultural strata of our daily existence. It spoke not from the future, nor from an alternative present, but in a puzzling way, from an ur-past.

Nevertheless, Huyghe does not fully depart from the structures through which we interpret our surroundings. As one progresses from the outside to the heart of the site, the meandering path dips into puddles, placing the viewer (who is incidentally worrying about his shoes) within the archetypal hero quest. The entire piece rests on narrative—it looks like a Jeff Wall photo—a seemingly purposeful shortcoming that suggests the impossibility of completely escaping our conceptions of existence.

Tino Sehgal’s “This Variation” (2012) was another example of this. The spectator unwillingly becomes a participant as they walk into a completely dark room. Like, beginning of time dark. The first instinct was to spatially constitute the boundary of the stage. Where do I stop, and where do they start? There wasn’t one, just the shuffling of bodies. Then, the room ignited in sound as dozens of performers, some just inches away, started singing “Good Vibrations.” Although at times embattled, dOCUMENTA (13) felt like art could do anything, even relate the Big Bang to the Beach Boys.