All images in this essay are stills from the Resorts World Miami promotional video, uploaded onto Youtube.com on September 14, 2011. Available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wfnLzgNi3VQ

The moment in which visual artists faced the Thing took place between 2000 and, let’s say, mid-decade. It was simply an unintended consequence of the fact that what mass media — assigned with giving form to the Thing — had to offer wasn’t sticking. TV was trying with CSI Miami; Hollywood with Bad Boys and 2 Fast 2 Furious. Music failed with a phony dance party thing (e.g., Will Smith) and Latin crossovers. Sports delivered Shaq and almost got the job done. Splashing in a pool of failures, artists had a shot. Probably the longest shot imaginable, but a shot.

Institutions sensed it. With exhibitions like Publikulture at the Museum of Art Fort Lauderdale in 2000 and The House at MoCA the following year, Miami artists became the rage. A few locals even got exported before a giant fair-mothership landed, absolving us from further action and risk. Institutions retreated to their timid ways. Collectors learned to adroitly negotiate whatever cultural capital (or potential) the city had for personal ends. Or maybe — dagger to the heart — artists just couldn’t deliver.

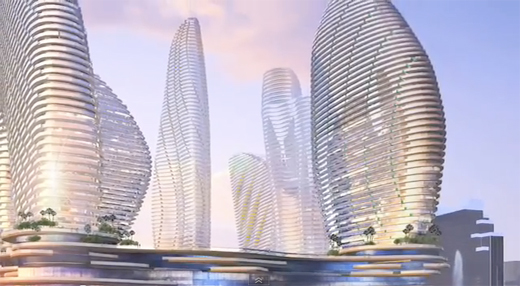

In the end, architecture stepped up. It started with the massive quasi-generic condo boom, punctuated by a few landmark pieces: Herzog & de Meuron’s Lincoln Road parking garage and Frank Gehry’s New World Center are examples. But this was merely a warm-up. A preview of the Thing’s imminent mutation, the coming Big One, is indexed by the volumes and embodied ideologies found in videos promoting Miami developments. From the Port of Miami’s master plan to Miapolis and Resorts World Miami, it’s this ludicrous architecture of kitsch-marvels-as-simulated-New-Urbanist-enclaves that will give shape to our historical moment.

These promotional videos are invaluable. They have more to say about the city than anything in local galleries and museums, in movie theaters or on cable. They map the genome of what’s coming. They’re also the material of a future archeology — the hieroglyphs of some 23rd century academic tasked with understanding the underwater ruins of an ancient coastal city. Immediate action should be taken to establish criteria with which to evaluate these videos. Film studies classes and humanities seminars should be restructured ASAP. The Wolfsonian can’t begin to archive them soon enough.

Rendering of Resorts World Miami

Rendering of Resorts World Miami

Rendering of Resorts World Miami