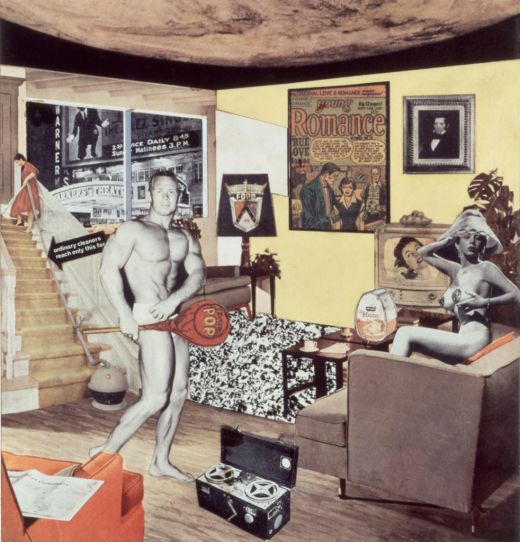

Richard Hamilton, Just what is it that makes today's homes so different, so appealing? 1956. Collage, 26 cm x 24.8 cm.

February 13 – May 16, 2014

Richard Hamilton famously claimed that for him, Braun’s industrial design was as inspirational as Mont Sainte-Victoire was for Paul Cézanne. The sleek modern lines of Braun’s eponymous toasters were his phenomenological muses. This analogy provides great insight into Hamilton’s eclectic body of work. In fact, as one of the forerunners of British pop art, his acute sensitivity to the seductive aesthetics of products provides one of the central modus operandi of his practice. The retrospective exhibition Richard Hamilton, currently on view at Tate Modern (curated by Mark Godfrey, Paul Schimmel, Vicente Todolí and Hannah Dewar) charts a career shaped by multiple trajectories, yet always underpinned by a profound fascination with the role of media and mediation in everyday life. Like Cézanne’s landscape studies of nearness and distance, Hamilton’s art recurrently investigates sensational reality and sensorial perception. Regarding culture through the perspectival lens of modern technologies, in particular focusing on the changing relations between images and information, Hamilton’s career spanned the 1940s through 2011. This ambitious exhibition tackles the prolific production of one of Britain’s most influential artists by displaying his interminable curiosity over the course of 18 rooms. Each space surprises the viewer in new ways, one upon the chronological heels of another.

Among the first rooms of the exhibition are recreations of Hamilton’s early installations, including the famous “Fun House” structure from the Independent Group’s This is Tomorrow exhibition at the ICA in 1956. Working against the cultural provincialism of post-war Britain, the piece consists of interactive passageways, Duchampian roto-reliefs, and a microphone into which visitors can liberally express anything they so choose. This room-sized composition is montaged with a cacophony of amusing pop culture images ranging from Marilyn Monroe, a massive robot, and a poster reproduction of Vincent Van Gogh’s “Starry Night.” Encountering this work at the outset of the exhibition, in addition to Hamilton’s most renowned work: “Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different? so appealing?” (1956), sets the logic of this retrospective in motion and announces the artist’s commitment to break down the barriers between art, technology, design, and architecture. For while Hamilton and the Independent Group were obsessive about the future, the new, and the glamorous, they also recognized the disorienting capacities of consumer culture itself. Hamilton articulated this complex attitude towards contemporary life in a 1963 article in Living Arts magazine, stating “An art of affirmatory intention is not uncritical.” The balancing act between the two positions, between celebration and doubt, are detectable throughout Hamilton’s oeuvre. Its clear nod to Marcel Duchamp’s brand of “ironic affirmation,” and traces of the older artist’s about-face performance of meta-critique, are undeniably present.

In fact, as evidence of Hamilton’s appreciation of Duchamp’s savvy Pyrrhonian skepticism, Hamilton organized The almost complete works of Marcel Duchamp at the Tate Gallery in 1966, in close conversation with Duchamp. It was the only retrospective of Duchamp’s work to appear in Britain. Their friendship speaks volumes regarding the affinities between the two artists and Hamilton’s role in championing the elder artist’s work. Realizing that the enigmatic “Large Glass” (1915-1923) was too fragile to travel from Philadelphia, Duchamp gave Hamilton permission to make a reconstruction. Hamilton’s laboriously recreated copy, though sans fractured glass, is on view in the current exhibition and provides a suggestive conversation starter regarding the ways in which chance operations and conventions of labor oscillate in Pop art.

The device of humor frequently negotiates this interplay in Hamilton’s art. Whether in the comic form of a painted subject’s breast buoyantly pressed against a plexi-enclosure in “Pin-Up” (1961), or the scatological and yet romanticized paintings of fashion models relieving themselves in the “Flowers and Shit” series from the 1970s, inspired by an amusing collection of postcards heralding the laxative powers of Eaux de Miers in Southwest France. Both abstracted and exaggerated, these voyeuristic works expose the vulnerable side of glamor.

“The Critic Laughs” features a schmaltzy television advertisement for a pair of gruesome dentures mounted onto a handheld electric toothbrush. A voice over describes this as an object of desire “for the connoisseur who has everything,” “a perfect marriage of form and function.” Filmed as a parody of an erotic encounter between a beguiling woman and a dashing leading man, the bizarre dialectic of the piece mocks commodity fetishism in its most melodramatic form. Filmed as part of the seventh episode of the Robert Hughes’ 1980 BBC documentary television series, The Shock of the New, a witty multiple (one of sixty from 1971-72) with an accompanying customized case is also on display.

Moments of liminality and passage recur in numerous scenes throughout the exhibition. Both “Swingeing London 67” (1968-9) and “Unorthodox Rendition” (2009-10) take place in moving vehicles. The former is a painting depicting Mick Jagger handcuffed to Hamilton’s gallery owner, Robert Fraser, after their arrest for drug possession in February 1967, and the latter a painting of Mordechai Vanunu, the whistleblower returned illegally to Israel after revealing details of Israel’s nuclear weapons program to the British press. Both images focus on hands raised between faces and windows, captured in freeze-frame by a press camera. Jagger’s hand resists the paparazzi fervor while Vanunu’s reaches towards the camera, desperate for visibility—the words “hijacked in Rome” scrawled across his palm. Excessive visibility is put in counterpoint to political repression, a pivot that returns again in Hamilton’s mocking paintings of Tony Blair as cowboy in the stance of Warhol’s Elvis in “Shock and Awe” (2010) and in his “Maps of Palestine” series (2009). In each case, the stakes of visuality and imaging are taken up as the crucial fabric that shapes human reality.

“Lobby” (1988), like “Shit and Flowers,” was also inspired by a bizarre postcard. The original image featured a vacant Berlin hotel lobby, simultaneously mundane and intriguing, with a bland clinical interior filled with complex spatial designs including mirrored columns and illusory Escher-esque staircases. From this source material Hamilton produced a painting as well as a life-sized mimetic installation, recreating the scene from the uncanny tourist image, which he compared to Jean-Paul Sartre’s play No Exit, as ultimately “a metaphor for purgatory, the limbo in which we await transit to another condition.” This flavor of existentialism also typifies Hamilton’s extensive collection of polaroid portraits. Produced between 1971 and 2001, each photograph shows Hamilton subjected to the whims of artists and friends ranging from Francis Bacon, Man Ray, and Dieter Roth, to John Lennon, Roy Lichtenstein, and Marcel Broodthaers, among others. Each is ironically marked by the signature style of its author, despite the apparently objective nature of the camera.

Artistic authorship perpetually contends with meeting the eclecticism of contemporary life on its own terms in this exhibition. Never providing a clear answer to the persistent question of “Just what is it…”, Hamilton’s artwork nevertheless unravels the perceived tensions between conceptualist and materialist approaches. Superficial oppositions are undone, revealing how experience is always mediated, and suggesting the productive and creative spaces that can be produced by curiosity conjoined with affirmative irony.