Genesis' notes on the class whiteboard. Image courtesy Jarrett Earnest

Genesis' notes on the class whiteboard. Image courtesy Jarrett Earnest

One thing we’ve been thinking when talking to people lately is, What do they think the purpose of art is? Why are they making art? Why do they want to go to an art college or a residency or what have you? What’s the purpose? Most people don’t know—this is one of the awful things that we’ve discovered—so ponder on it for a minute. At Yale we asked how many people want to have a career and want to be successful? And about forty percent raised their hands straight away. And then we said, how many people here know better and don’t even know what they want to do next? And that was the rest, sixty percent. That’s one of the things that separates what we’ve done from the so-called art world. We never went to art college, so everything that we’ve done has been self-discovered. Luckily, in the ’60s in England there used to be a weekly magazine with a name like Art, and it was the story of art from the stone age through Modern times, and you’d get one a week until you had a big set like an encyclopedia and we actually got a lot out of that. It was really healthy in retrospect because it gave us a picture of the whole thing: How did it begin? A lot of people make art and want “success”—they want to be recognized, they want to be “branded,” they want people to know what they’re doing and who they are. Do you want to make money?—A lot of them, that is what they want, so they have to have a formula. Something that is recognizable, so that a rich person in their penthouse can have a Damian Hirst with dots and their friend will come ‘round, who is also very rich, and say, Oh, you have a Damian Hirst, I’ve got one too. How much was yours? Mine was ten million. Well, mine was fourteen million. Well mine’s bigger than yours, and so on. It’s a whole ego thing, and it’s like people are serving other people’s egos. To me that’s not art.

So what is art? What is the process that makes it art to me? For me it’s a way of life, but it’s not just a way of life, it is life. For me making art is the result of a spiritual search for meaning in life and a way of trying to understand existence, society, culture, people, and why are we here. Why are we really here?—All those big questions is what art is for. More than that, it’s a devotion. It’s a calling. It’s like becoming a surgeon or a priest— when you create, you create on behalf of humanity, whether they like it or not. And you’re hoping that through the process you’ll find some wisdom too and want to share it, which is why we’re doing this talk, to try and share whatever we think we’ve found out. It’s functional.

We read those books when we were young and thought about the stone age and the early days of our species, thinking about how art began, and realized that it began to make things happen. In the beginning people weren’t sure the sun would come back again. It would get dark and they would panic—how can we live without that sun? So they would sing to the sun and draw the sun and it would come back. So that meant that this process of making and saying and describing made things happen, it made the sun come back, it made life begin, it made babies come, magically. And of course people make rituals: a baby is born, it survives, you celebrate. So all of it begins with things that happen, are produced, celebrations and illustrations and passing down what they’ve learned about things: how to make fire, where the best water is, and so on. All of that is where art begins. Art is magic. In the Renaissance you’ve got the beginning of our modern situation, where a combination of religion and money starts corrupting the function of art. Now there are theories that some of that art still has meaning through hidden alchemical messages but it’s fuck-all-use to us. Doesn’t do anything for us. So, where do we go from there?

The beginning of my art activity was to explore possibilities. We got really lucky in the ’60s. It was a time when people were thinking of any and every alternative to what was the traditional way of doing things. So you’ve got performance, you’ve got kinetic art, mixed-media events, performance that looked like ballet, ballet that looked like sculpture, sculpture that looked like painting, and everything got jumbled up and you were free. We were at University and this group came through called the Exploding Galaxy, started by David Medalla. He was a child prodigy, and was one of the first kinetic artists—he made these miniature washing machines that spewed out bubbles in different shapes and that was the sculpture. He decided that art had to be about life, had to be interacting with anybody—that art can’t be elitist or arrogant but has to relate to the people, and has to relate to the people and their experience. So they came to my university and at that point half of them had left to India to learn dance so they were short of people and they asked me to join in, and that’s what happened. When they left they gave me their phone and said, if you’re ever in London and you’re stuck for somewhere to sleep, come and see us. We decided to quit University. We’d been doing spontaneous events in the university to crate mayhem; at one point we announced we were making a documentary about a sit-in in the administration block, and the idea was people would show up because they wanted to be in the film and it would create a sit-in anyway because it would block the place. It didn’t work, sadly.

We went to London because we heard the Rolling Stones were playing in Hyde Park, and they did, and they were terrible. Brian Jones had just been murdered, and so they were doing this concert in his honor. They had this idea of releasing all these white butterflies as [Mick] Jaggar read a poem. They forgot that it was a really hot day and all the butterflies were dead. So they had people running up the stage throwing them up into the air to make them look alive—and that sort of sums up the Rolling Stones right there. Of course we didn’t know where we were going to sleep so we rang that number and went to Islington where they were living as a commune in this house, and that was one of the three main influences on everything we ever did since. They had lots of rules: first of all they knocked the walls out of the bathroom so if you went in to piss or shit or whatever, everyone could watch you. If you want to have a bath everyone could watch you. The whole basement was one big space. Everyone’s clothes were put in a box every night, and whoever got up first had first pick of the clothes and whoever got up last got what was left. All the money was put in a lock box and if you wanted money to buy something you had to convince everybody else that you should have it. If you said, Oh I need to get to the other side of London, can I have money for the subway? They might say, Can’t you steal a bike? Can’t you walk? When do you have to be there? Can’t you go beg? Why do you need money? And of course, you don’t, really. We had this kind of game, it comes from [George Ivanovich] Gurdjieff, called the “Stop Game”. Anytime you said “stop”, everyone would freeze, and you would interrogate them: why is your hair always the same, is that all you can think of doing with your hair, don’t you have any imagination? By the way, why are you wearing shoes? Do shoes have to look like that? Couldn’t they be something else? Why do you have to wear clothes? On and on—anything and everything could be challenged. And would be. I got picked on all the time for playing with my fingernails. They tied my fingers together at one point to make me aware of what I was doing with my fingers. That was a really rigorous environment. You had to sleep in a different place every night. You were allowed a sleeping bag, which we had: we slept on the roof between the chimneys, we slept on the scaffolding outside when they were fixing the house, we slept in the garden, in the toilet area, in the hallways by the doors, all around. And it worked pretty well. What we were trying to do was recognize how much of our behavior is habitual. How much of it is done without thinking and is unnecessary, and how often it’s redundant and the way that we do things are just because that is the way you’ve done them before. The idea was to move from habit to constantly being in a state of awareness in the present. So, before someone challenged you, you’re already thinking, how else can I do this? I learned a new way of making bread, called density bread, because it was unleavened. We also tried to design a new way of writing, which we still use to this day in an extended form.

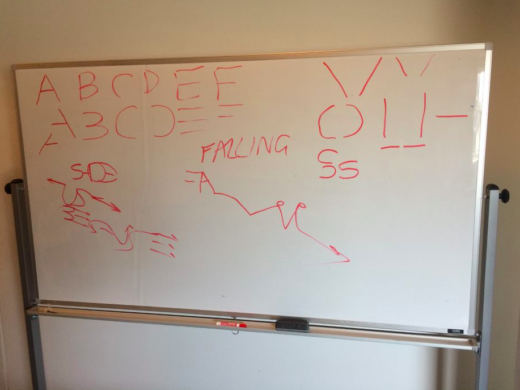

We were trying to find a way to make writing flexible instead of fixed. All we used were these few marks. What it does is, everything single thing you write, you’re thinking about its structure, and you can suddenly do things like instead of writing “FALLING” like that, you can combine them like this.

[Writes on the whiteboard, see image.]

So you start to have a different relationship with language. Here’s “SHOE”:

This came back later on when we started to take Magick a lot more seriously—we often use it for sigils.

MFU: I had no idea how it evolved. You were doing that when you were at the Exploding Galaxy?

GBPO: Yeah, in ’69. You can do so many things. It’s much more graphic. It becomes a little piece of art in and of itself. So, that, and also stripping down behavior were the two things we took from that experience. We realized just how much of our personality is other people. If you go back to when you parents got pregnant, before you’re even born, they’re already talking about their expectations of what you’re going to be. Are you going to be a boy or a girl, and what do you think you’ll be like if you’re either of those? And all their friends will have a say about what their expectations might be, and so will society, and so will religion. And so, from the very beginning, we’re being bombarded by what everyone else’s ideas of you might be. And they are constructing you. You can’t help it. So my idea of art is to reject everything that’s led up to the point where you want to be an artist. One of the best ways to do that is to change your name. To reject that history, and a lot of people find that very difficult. My parents cried more about that than anything else we ever did. Why don’t you want to keep my name? That’s not what it’s about, it’s about choosing your own way—building your own self, free from every influence you can get rid of. Our name came from a nickname, but we adopted it and changed it legally.

The whole thing that we took from the Galaxy was trying to remain constantly aware of the ease of falling back into doing things the same way, and trying to make sure you do things the way that you do them because it’s the best way for you at that moment in time. We left because they did the classic Animal Farm thing: we came back and the girlfriend of Fitz, who was the one nominally in charge, was wearing brand-new handmade bottle-green ankle boots. We said: Stop. Where the fuck did you get those? She said: Oh Fitz got them for my birthday. And you can imagine how it went: why the fuck do you need a birthday? And then they found small box room upstairs and started sleeping in it together every night. And it was only me who spoke up. Then there was a meeting, we were being a “destructive influence on the house” by calling them on it, so they stopped letting me have food and stopped speaking to me, so after two or three weeks we said, fuck this, we still believe in a lot of the ideas but we can’t stay here anymore, and we left. We went hitchhiking and ended back up in the North where we went in University to visit friends. On the way there we stopped off at my parents to explain what we were up to and they had just moved to somewhere near Whales. One day they said, we want to take you out, do you want to go for a drive?—Alright. So I’m in the back of their car, and you know how sometimes you get tired and close your eyes against the window and there is that nice little flickering behind your eyes? All of a sudden, we started hearing voices, and seeing shapes and words and visions. We just got filled with all this information pouring in. It’s embarrassing all these years later, we only figured out much later that it was a “flicker experience,” exactly like the kind Brion Gysin had that became “dream machine.” But it never dawned on me for all those years, it was just this mystical experience and when we got back to their house we wrote everything down in notebooks and drew what we saw and that was where we got the word COUM, which originally stood for something: Cosmic Organicism of the Universal Molecular. Which is a bit of a mouthful, so we just used COUM, but it actually fits in perfectly with what they’ve discovered with quantum physics lately, so in a way it was revelation of the structure of the universe outside time.

MFU: What is a flicker effect?

GBPO: There is a film you can watch called Flicker by somebody called Nick Sheehan. He is Canadian. Brion Gysin was close friends with William Burroughs and they both lived in this hotel in Paris, which was called the Beat Hotel. One day Brion was in a coach in the south of France and he did the same thing, which is why it is dumb that it took me so long to realize: he leaned on the window and started to drift and of course in France in the south they have all these trees at regular intervals along the road so the shadows were flicking across his closed eyes, and all of a sudden he was having these psychedelic patterns and visions and swirls and he was fascinated with the effect. He told one of their friends, Ian Sommerville, about this and they figured out that the flicker at a certain speed of flicker on the eyes will trigger this effect. It also triggers epileptic fits in people who are prone to that. Bit by bit between them they designed what they called a “dream machine” which was a cylinder with holes cut in it with a lightbulb inside. They made it so it went onto an old record player and when you close your eyes and get them about half a foot away, you start to see things. Most people see psychedelic patterns. Some go beyond that and see landscapes and other planets and strange beings.

MFU: Do you have to be asleep?

GBPO: Oh no, no you just close your eyes. As Brion used to say: it’s the only artwork you look at with your eyes closed. Which is a rather a wonderful thought isn’t it? The Pompidou has Brion’s dream machine. A jeweler in Switzerland did an edition of five perfect ones. We have one that is just a metal cylinder with holes and it works just fine.

He actually tried to get Phillips to mass produce it in the ’60s as a drugless high, so that people who were against drugs don’t have to be against this, but it never quite got through. I think they were suspicious of it because it was making people trip, even though you could just open your eyes and make it stop.

MFU: Genesis, do you think that kind of corrupted social hierarchy that formed in Exploding Galaxy is inevitable in any kind of group? Or how can that be avoided?

GBPO: Well, it requires constant re-assessment of the self every day. And an awareness of the danger of that happening. People really do like to let someone else take over the responsibility of their choices. That was something with Thee Temple of Psychick Youth (TOPY) that we were really aware of, and fought really hard to prevent. We found that people were regularly trying to build a pyramid structure of importance. And we fought tooth and nail to stop it. For example, when people wrote in and wanted to become more active and wanted to do sigils, at the beginning we would give them all the same name. If they were biologically female they would be a Kali and a number, so you’d say “Kali Three”, “Kali two-three” or “Kali four-one;” biological males were Edens and they would be numbered too. There was never a number one or two, and we knew that would be a bad idea straight away. There was actually twenty-three of “twenty-three” because we knew people wanted to be number twenty-three because that is our special number, so they’d boast about being “Eden two-three” and then “oh, I’m two-three as well!” and they would be upset. And for a while it worked, but then we noticed people were saying, “I’m Eden four-one and you’re Eden three-zero-five, a long time after we joined.” So then we just jumbled them all up at random, and then we changed the genders too so there was no way of figuring out who was higher or lower in any hierarchy. People tried every trick in the book. You know, we never said people were “members” we just said people were either “connected” or chose to be “disconnected.” You’re just actively involved or not. You’re not a member. Membership implies that you’re accepting some basic set of rules and we weren’t doing that.

We’ve jumped ahead! We were only going to talk about COUM a little bit anyway. To go back to the Ho-Ho Fun House for a minute, which we started after we left the Exploding Galaxy, we wanted to bring the idea of the “stop game” a little bit further. We had an extra room we called the “costume room.” We had these different outfits that were characters, sort of stereotypes. There was one called “Harriet Straightlace” and she was a middle-aged woman who hated everything modern and complained about the way things cost more and how young people behaved, and all the usual things that you get from a certain kind of person. There was “Mr. Alienbrain” who was all day-glow orange and had a hat made out of old radios for his head. There was a rollerskating clown who was the jester or trickster. So every costume had a character and every Friday night the people involved would come meet and take on a character and wear the outfit for all of Saturday and Sunday. So if you were Harriet Straightlace, you had to behave like her everywhere you went for two days, without explaining to anyone else why you were doing it. It was actually really rigorous and difficult to keep up but it was also tremendous fun, especially when she went shopping and Harriet would get incensed, I want to see the manager! It didn’t used to cost this! And so on. And the Alienbrain would just always be baffled by human behavior, why do they do the things they do? Is that a religious experience or are they just shopping? It was another way of doing the same thing, another way of understanding how we fall back into characters that we build ourselves, or have been given, or accepted—whether it’s a socioeconomic group or an ethnic group or gender or whatever, just constantly looking how you behave and what are your real motives for how you behave.

It’s not like your usual art class is it? We weren’t worrying about making art at all, we were interested in finding out more about behavior and character, and how to eventually, as far as we could, wipe the slate clean and choose very consciously what you wanted to be, as a person—and during that, because we used to go out into the town, people noticed us of course, because there was this band of very weird looking people in a place that was very working class and a lot of unemployment, so this brightly colored little tribe caught people’s attention. One day this man came up to us and said, I’m the director of the Hull Arts Center and what you’re doing is performance art. And we thought, don’t be stupid. Then he said, I’ll give you two hundred pounds if you’ll come do this at the art center, and we said, yes, it’s performance art! And that is how we switched across really. At the same time we were having a lot of problems with the police. We had gotten involved with the Hell’s Angels—well at first it started because they tried to invade the Ho-Ho Funhouse. One night there was banging on the doors of the first Ho-Ho Funhouse, and we looked out the windows and there was all the Hell’s Angles, and the Freewheelers motorcycle club from the south, about fifty of them, and they were banging on the door and saying, Let us in; we want to party. Someone had told them my name because they were yelling my name. We got up and were actually in a Victorian nightie. We went down stairs in the nightie with an axe, and locked the door behind us so they couldn’t get in if they charged, and we stood there looking out at this sea of bikers. What the fuck were we going to do? We think in terms of all that stuff we’d done becoming characters, we went into an “I don’t care, I’m not afraid” character. We saw the Hells Angel that had once been pointed out to me as the most violent and went up to him and gave him a big hug and said, How are you doing, I haven’t seen you in ages! And he was so shocked he didn’t do anything. Ah, he’s not afraid. So they all smiled out and nothing happened. I said, What do you want?—We want to party! So I said, let’s go inside and have a party. And we did. And they behaved really well. We said, you can’t go up that side because that is where we sleep but you can do what you want on this side. It was a semi-derelict warehouse. They partied for two days, and it became their clubhouse on the weekends. They used to come on their bikes and bring us milk and food for the animals, groceries and stuff. The police didn’t like this. One day we were all hanging out and the police came and couldn’t get in, so we were all hanging out the windows yelling at them and teasing them. That is when we painted “HO-HO FUN HOUSE” on the outside, climbed out a third-floor window. And they went away in the end. But then one day they came up to the second Funhouse and we were still having the Angels come around, and said, if you’re still here at the end of the week you’ll be imprisoned. And at that moment three of the COUM people were in prison, so we knew it was real. One of them, Ray Harvey, who died last year, was the only black person in the town at that time. He was tattooed head to toe in 1969, which was pretty unusual. He was illiterate, because once I asked him, why don’t you leave the town the police are always picking on you, he said, because I’ve memorized the streets, if I go anywhere else I won’t know where I am. So he was trapped by not being able to read or write. One day they arrested him because he was in a derelict building and they saw him pick up an empty milk bottle and put it back down and they said he was trying to “steal” it and gave him six months in prison. Then there was Lelly who was actually a professional burglar, but only burgled police houses. He had a band called The Burglars as well. He was pretty eccentric. He was the Reverend Elly Moore, and we gave him a vicar’s outfit. They gave him six years when they caught him. So the police were serious. And they knew we were somehow connected to all this bad behavior even though we weren’t doing it, so they just thought it was somehow our fault to be the catalyst for all this to happen, so we put all our stuff in a truck and drove to London and continued basically doing performances and being ourselves.

In the beginning it was more like street theatre, and as time went by we started to think deeper about behavior, why are there certain taboos about sexual behavior? Why are there rules and regulations about being naked? Why is it ok to be topless on a beach but not on a bus? Who’s making those rules and each country has a completely different set of rules that police how we behave, especially with regards to the body, so we decided that the body was a really vital exploration, and we started to do all our performances naked or become naked and we were interested in what’s real and what’s fake and how do people respond to things given more information. At that point there were only three of us in London, Sleazy, me and Cosi Fanni Tutti. Cosi would put fruit inside skin tight clothing, sort of leotards and so on, and then slice them with knives, and if you have peaches its really like flesh, and so she would do all this apparent mutilation but with fruit. It would smell nice but they would be shocked because at a certain distance they couldn’t be sure if it was real. Where as we would do real things with knives and cuts and so on but it didn’t’ look dramatic, and only when they’d get nearer and they’d see real blood that it would suddenly change. And instead of thinking that you were innocuous they would think that you’re shocking. So information changes the way that people respond. It’s not the thing itself. It’s the information they receive. For example, when we did Industrial Records, the logo was a photograph that we brought back from Auschwitz when we went there, of the ovens. We did it just in black and white and it looked like a factory with a chimney, which is of course was what it was, a death factory. Hence the name “music from the death factory”. But no-one knew it was a picture of Auschwitz, they just thought it was some old factory somewhere, and after about a year or so I was said, you know what that picture is, and just like that people thought we were Nazis. All because of that information. Now of course it’s switched back. It’s this “amazing legacy” that is treated as though its holy or special, but it’s still just images, sounds.

MFU: If the information changes the way an audience responds to a thing, how does that position an artist in creating or shaping that information?

GBPO: It’s something to be aware of when you do something, that’s how we look at it. You can play the game like we did with that logo. We’ve done it with lyrics too: we’ve written lyrics that were ambiguous.

MFU: Like the Psychic TV song “White Nights?”

GBPO: “White Nights” is a song that we did on the album Dreams Less Sweet, which is done in the style of the Beach Boys with harmonies and everything—it actually has sixties musicians playing on it. But all the lyrics are quotes from Jim Jones as everybody was committing suicide. But unless you’d know that, you’d never guess. We’ve done that with a few things. There’s also one that is sung in Latin, which is actually from [Richard von] Krafft-Ebing’s Psychopathia Sexualis, which was the first attempt to create an encyclopedia of different psychosexual aberrations, and whenever it got really naughty for its Victorian time it would switch into Latin, so we did a song using just the Latin parts that were too outrageous for the Victorians to hear. It’s done by opera singers who have really beautifully choral arrangements that sound like Latin chanting, but it was actually the part of Psychopathia Sexualis about someone obsessed with having sex with little boys. No one has actually ever figured that out. Also on that album is “Always is Always Forever,” which is a Charlie Mason song, also sung by opera singers and done very beautifully. That whole album is where we were playing with all that deliberately.

We didn’t know we were going to use those Jim Jones recordings for lyrics to a song, we just wanted to know what it sounded like, but that is another thing that we were going to get to, which is “patience.” A lot of what we create now uses things that we’ve sometimes had for twenty or thirty years, on boxes or on shelves, until they seem appropriate for something, like that tape, we had it for years before we used it. We didn’t know we were going to use it for that song, but that seemed like the most interesting use we could come up with.

So we started doing these performances that were really brutal toward my body. And one of the things we noticed was that we started having these out of body experiences— shamanic experiences—sometimes we were speaking in tongues, sometimes we were seeing visions, there was a time we were able to drink poison and it didn’t affect us at all—we don’t recommend that though by the way. But it seemed we were going in some direction or that we were finding things out, that didn’t’ really need to be in an art context anymore, we decided to withdraw from an art context all together, but to continue researching what was happening with the mind and body. We started doing ever more precise rituals using our body and different types of restriction—whether it be bondage or suspension—for instance once we were wrapped in wolf skins and put in a coffin, which was suspended on chains and we were left for twelve hours after having taken a large amount of psychedelics before they put us in the coffin. When they brought us out the first words were, Now I know what time is. And we realized that time is an energy. This has also been agreed by physicists of the last few years. That became fascinating: are there ways for the human brain to achieve states or revelations that move us forwards as a species? It became not about art any more, it became we’ve taken out all these habits and stereotypes, we’ve stripped away and stripped away, and now we’re in the brain, mind and consciousness. And that seemed to be the most important thing to explore, and it has a responsibility to the species.

It becomes about evolution, it doesn’t become about art—the things that you make are just the detritus of the process of trying to understand consciousness. And what we can be and what we’re capable of being in our minds. That is where the Temple of Psychic Youth comes in, and at one point there were nearly ten thousand people involved, and several occasions where we had people coordinating the times in several different territories all having orgasms at the same time, with the same idea of what they want to have happen. Which has never been done before or since. And what we found was the people seemed to have an effect on what happened to them, and that is what the sigils are in THEE GREY BOOK. We noticed that if we were doing this and we weren’t bothering to add on the names of Egyptian gods or religious concepts or tribal disciplines or anything else, but it was just, the brain is capable of amazing things and if you stress it and push it and open it up and allow it to just explore beyond the edges of the body, and that that can make things happen. It says you put down your real desire, and a lot of people start out with things like, I really wish I had a boyfriend, or a girlfriend, or pay the rent—really banal things. And often they would write in and say, it really happened. But that is not very satisfying. After a while, if you’re really doing it with thought, you start to think those things are not really important. What do you really want? And you start to realize what you say is not your real desire. What a lot of us do is we say things in short hand, so people say, I really want a girlfriend, but what they’re thinking is, I really want a girlfriend who is this particular way and who loves me like this and has always known that they want this and their occupation is this. There is a whole hologram of extra information that we don’t speak but it’s there and one of the thing that sigilizing helps you do is start telling yourself the whole story, and it’s not really one thing, it’s something else. It’s not just that you want a girlfriend, it’s that you want to be loved in a particular way that will make you free to do something else. Or, by being loved that way you can relax enough to maximize your ability to do something. You start to get down to the heart of who you are, and when you get down to the heart of who you are it’s much easier to get to the things you want to have happen.

And on that journey, that process changes with those revelations, and that’s when the things that have been hanging around come back in. It’s like, at one point, when we met Lady Jaye she was a dominatrix but also a registered nurse. The first gift she ever sent me in the post was a Chanel No. 5 bottle filled with her blood. When I got that I thought, this is the right person for me. Wow! So we sent one back twice the size as a “yes.” So we put them in the fridge, and then Lady Jaye dropped her body in 2007 and we moved to the apartment that we’re in now and somehow the bigger bottle with my blood got put in the freezer and not just the fridge and it froze solid, and when things freeze solid they expand and the bottle cracked. So we couldn’t take it back out of the freezer because it would melt and spill. We were asked later by the Armory Show to make a piece for them and we’d been thinking about this bottle and how it had broken and suddenly out of nowhere it assembled itself as an idea—it’s almost like there is a little engine in there now that chops things up and re-assembles them, because of all these processes that we’ve been through, but suddenly we’ve seen this piece that was Lady Jaye’s bottle of blood, and then my broken bottle and just let them warm up and see what happened when they started melting. My intern at the time had started working with this really high-end photographer and he had all these stop-frame cameras and he was interested in filming it for me. We got a steel table and checked that it was totally level. Then we put a Tibetan prayer shawl and put the two bottles on it and filmed it from the front, one side and above. And we left it at room temperature. The final piece is a 90 second video. At first my blood leaks out, as you would expect, and at first it’s just a circular pool around the bottle and then suddenly it shoots across to Jaye’s bottle and surrounds her bottle as well, against the laws of physics. My answer to things like that is always, well of course it did. That’s the “of course factor,” but we didn’t know that was going to happen. It’s a beautiful piece.

MFU: But beyond the video for that piece there are images and the shawl?

GBPO: The shawl was doubled over so afterwards we cut the two pieces with the stains on them and framed those.

When we were in Katmandu, we were there a week before this friend of mine, Hazel arrived. We got ill, so ill that when she finally saw me she took me straight to the hospital. They examined us with sonograms and X-rays and everything, and said, your gallbladder is disintegrating and you’ll be dead in two or three days if you don’t have it taken out. We think you should change your flight and return to New York in the morning and have it removed immediately. And we said, No, we’re not leaving. It took me twenty-four hours to get here, I’m not leaving Katmandu. In those days you could buy liquid ketamine in bottles over the counters and we’d been using ketamine on and off for meditation because it’s really good for getting out of body experiences if you use it correctly. So we got that and then we went back to the hotel and started to use that to meditate on healing inside my body. In another few days, we went back to the doctors and they did all the tests and said, We don’t know why but your gallbladder is completely normal. We would argue that is because of all this other work that we’ve done. We just knew it would work, we couldn’t explain it, but part of me knew that was the right thing to do. Poor old Hazel was freaking out. When we went inside it was like this really ancient ruined city that was all very pale white and grey and crumbling like it was made out of limestone. You could see the remains of temples—it was all very interesting. We didn’t repair the temples or anything but somehow we repaired me. Which is a strange place to end up with art isn’t it, in Katmandu, healing your gallbladder.

The other thing we’ve not mentioned is cut-ups, which is a really important part of it too. Do any of you know about the cut-ups? [William S.] Burroughs and Gysin? Brion Gysin, who discovered the dream machine, also discovered this technique which he called the cut-ups. He was working on collage in his room in the beat hotel one day using an exact-o knife with some newspaper underneath so he didn’t cut the table. When he lifted his pictures, he saw that he cut these squares out of the newspaper and idly started to put them back together and read them across and discovered a totally different piece of writing. He started to type them up by reading them across. When he showed Burroughs he said “You’ve liberated writing into this whole new dimension. They did several books of cut-ups and started to believe you could actually predict the future sometimes, as Burroughs would say, lets see what it really says. There is a bit of his cut-ups on an album we released, Nothing Here Now But The Recordings, where there’s a letter from his lawyer that he’s cutting up from England, and as he reads it’s its blah blah blah money, money, money, ah I see, it’s all about money. And he throws it away. So, by cutting things up, it’s one of the only ways to break the inevitably of ourselves trying to find form and meaning in the linear way that we look at things. And if you chop it up and reassemble it as random as you can get, it’s the only way you can get collisions that you wouldn’t get any other way, and they can be very revealing and inspiring and they can give you insight you won’t get with any other system. They started to experiment with tape recorders, chopping up bits of radio, bits of speaking, and just backing it forward and backward at random and hitting record. That album, Nothing Here Now But The Recordings, has been re-released by Dais records and it’s got a lot of those early experiments. They also did things with film. One tape is actually called The Cut-Ups where they had an old lady just assemble little pieces of the same length into a twenty-three minute film. It was first shown in a porno theatre in London and the owner said that he’d never seen so many things left behind, shoes and underwear and bags—it was so deranged people left things.

And that is a tool that we’ve used in every possible way ever since. Behaviors—a lot of our rituals were cut-ups of behaviors; objects; images; ideas—almost everything we make is a cut-up of some kind.

For instance, we kept all these shoes that belonged to dominatrices, strippers and hookers that we knew, and just stuck them in a big box. About nine years later we’d been to Africa and we’d brought back these little fetish objects—pythons made out of iron and different symbolic shapes—and we took a shoe and started to decorate it with these different symbolic things, hair from Jaye and fur from the dog, and turned them into these beautiful objects, which are called “shoe horns.” We also had a bag of horns that we found in a junk shop somewhere—that is how it began. My niece wanted to know how we came up with ideas and we said, we just stick things together like that shoe and that horn, and I stuck the horn onto the heel of the shoe. Oh, I’ve got a shoe horn. Then I thought, I like that, I think I’ll make some more shoe horns.

MFU: You were talking about cleaning the slate and starting from blank; along the journey did you find that some habits had some residual importance that you might have thought before were just a social construct?

GBPO: No. Nothing we can think of. The only habit we’ve kept is making art when we feel inspired. We went thirty years without showing anything to anyone, just doing things privately. Then one of my interns, Ben, happened to come across my collages and said, you should show people these. And it’s actually made it much more complicated to make things, because now there is an outside world that gives a certain value or importance or meaning to things that were really completely personal and separate from that world, and that can be really confusing. And that is when you have to use these disciplines to not let it affect what you make. We always think, do we really want to make another shoe sculpture or are we just doing them because people will like them? Or we like them? As long as the need to make it trumps the world outside’s opinion than we can make it, but if we felt like it was just for the sake of it, then we wouldn’t do it.

MFU: When you were talking about the life you were leading in the Ho-Ho Funhouse, and a lot of the chaos that was going on with constantly changing routines, you said that at that point you didn’t have a desire to make art, but would you say that you did that in order to clean the slate in order to make art—

GBPO: No, to clean the slate, not to make art.

MFU: But you didn’t continue living like that once you made art?

GBPO: Oh yeah, our lives have been pretty chaotic all the way through. For example, when we met Lady Jaye, she was a dominatrix, and within four or five years we were working as a female dominatrix in the same dungeon. We completely went into another personality, and we could do that partly because of all the other things we’ve done. And we did it for a while and then it was boring so we stopped.

MFU: I never connected that early experimental stuff with Exploding Galaxy to the later Pandrogyne work. Or the stuff around behavior to being a dominatrix.

GBPO: Oh yeah, it was another stereotype to be explored and deconstructed.

MFU: What was that coffin you got in? The sounds kind of scary and I can’t imagine being on psychedelics in that situation.

GBPO: Human beings are much more terrifying. And it’s not also like you say, Oh lets do that! You build up toward something like that, and then this idea comes to mind of being completely unable to distract the self from anything to do with touch so that the mind will just leave the body. The reason why we’d always have someone there, and why we have some of the cuts on our arm, is if you have an out of body experience like that you can travel so far but you don’t know if you’ll find your way back. If someone does something like hits or cuts you, it brings you back into the body again. Because you can truly get lost out there. We did things for years with Jaye with a tape recorder, paint, scissors, glue, things to collage with, and polaroid cameras, and we were trying to learn how to retrieve information that makes sense. You know you can take psychedelics and write down what you think is the meaning of the universe and you read it the next day and it says something like: CUPS OF TEA AND TEACUPS AND EGGS—Oh, I thought that was the meaning of the universe, and its gibberish. It takes a long time to start to bring back comprehensible information.

MFU: The way you started this talk was to ask, what is the purpose of art and why do you make it. I’d love everyone here to share their thoughts on that. Something that surprises me about being in the so-called “art world,” of which there are many, is that it’s the basis of what we’re all doing together and it’s not something that is brought out into discussion together. Perhaps it is so foundational that there is embarrassment about trying to have that conversation about what it is you think you’re doing as an artist.

I think the reason I feel artistic expression is a need in my life is that I’ve always felt a deep discomfort with the geographies I’ve lived in, the languages I’ve spoken, the times I’ve lived in, and art is the process of—

GBPO: Your relationship with all that.

MFU: Of belonging to something that allows me to articulate my relations to things. Because if I don’t, the work or the image doesn’t exist and I will always feel that discomfort.

GBPO: Does it matter if anyone else knows?

MFU: If they do it would be nice, but I don’t care. I was also going to add, that I’ve had a couple psychedelic experiences that were creatively transformative, one in which I saw what music looked like, full on just watching rhythm unfold and how certain melodies have colors. After watching that for thirty minutes I understood, rhythm is everything.

GBPO: Like with me and time, you understood rhythm. There is something else that we didn’t mention but that we meant to: We’ve noticed that the more you explore all these things, the more that irrational but fascinating things seem to occur. For example, when we went to West Africa for the first time, we went because my friend Hazel, who looked after me that time we nearly died in Katmandu, she said, You took me to Katmandu for a month so I’m going to take you to Africa because there is an amazing Voodoo festival and I want to go see it. The first night we got there we were sitting in a town square in Ouida, which is a tiny little coastal town and there are no streetlights or anything like that. Everyone was around a table about like this and we saw a tall figure in the shadows against the wall that seemed to just float along in these blue robes, and then he vanished. Then we blurted out loud, I bet that’s a high priest.—What? There is nothing there. So we all went to sleep and forgot about it and the next day these two guys in their early twenties who were our translators and guides said, would you like to come have dinner with our family?—Of course. So they took us back to the town square and we walked along that same wall and recessed into the wall was a doorway where their family lived—so the figure we saw hadn’t done anything magical he’d just gone through the doorway, we just couldn’t see it. So we went in and there is his father, who is about six foot eight in blue robes sitting on this big chair, and turns out he is the high priest of the Voodoo in that area. He looked at me and said to his son, you had a twin but she died and you’re wearing her earrings—and my hair was down so he couldn’t see them. We said, Yes, because we were wearing Jaye’s earrings and we consider her a twin. He said, you need a Jumu, so by the third day we were doing rituals and chants and sacrifices to create this version of Lady Jaye, to remain in contact with her spirit. And then Hazel said to me afterward, I knew something like that would happen if you were there, something like this always happens when you’re there. I said, oh thanks for telling me. It seems like those kinds of things happen more and more often if you open more and more and the whole process starts to feed itself in ways that you could never have planned in advance. We never imagined we’d be involved in Voodoo in West Africa, which became a documentary called Bight of the Twin (2016). One of the upsides of it all is that amazing things seem to come more and more often.

MFU: The question I actually had after watching Marie Losier’s film The Ballad of Genesis and Lady Jaye (2011) was you said you consider yourself as someone defined only by change, is there a foreseeable project or changes that you want to explore on the horizon?

GBPO: The last thing that we wrote down to talk about today was: CHANGE THEE WAY TO PERCEIVE AND CHANGE ALL MEMORY. Change is a constant need but we don’t do anything to force it. We look at everything from a deathbed—you know the Sufi saying, live every day as if it’s the last day of your life and that is the day your life will be judged. And so, everything we’ve done has been with that sense of unfinishedness, looking back from our deathbed. That is why we have such a longterm view of everything. We think, are we going to be satisfied by the way we reacted to these things up until where we are now? That is the most important part. Feeling that you haven’t corrupted or taken easy paths just because it was easy or you were tempted by something else. The need to be aware of and ready for change is constant.

MFU: I was interested in when you said that the first step in being an artist is rejecting what has been given to you, what you’ve inherited. The idea of CHANGE THEE WAY TO PERCEIVE AND CHANGE ALL MEMORY has me wondering how you perceive history and what history is.

GBPO: What you do is what you do and you live with it. We actually call it A-story. Burroughs said something to me which was actually really helpful which is try to avoid the world “the.” So, for instance, if someone is talking about “the future” you have to say, there’s no such thing as “the future” there is a future and each person’s future is different so there are billions of futures. It’s a helpful thing to think at the back of your mind. And likewise, how you remember things changes based on what you’ve learned and perceived and how to analyze the current situation. It’s not for everybody, the idea of being in a constant state of flux and possibility. Or as my friend Tim Boston said, not just possibilities but impossibilities.

MFU: A-story is really great.

GBPO: Well, it’s not his or her, is it? It’s a story, and each story is different. So when someone says herstory, it’s just as limiting and with just as much baggage. So it’s always useful to try and look at language and find ways for it to be either more accurate or more flexible. Language has been a big part of everything we’ve done.

MFU: When do you first think of art as something that had a function in the world?

GBPO: My grandmother probably. The first cut-ups we saw were Max Ernst collages. My grandmother was a medium. She once confessed various things to me and she ended up so terrified that she stopped doing it and ended up a really radical Baptist Christian. At the age of ten my father gave me that book Seven Years in Tibet, and that was such another culture and had such another belief system that included the oracle and very different ways of structuring and perceiving the world. It was a process of more and more information, calling into question what we’d been fed. Then we discovered traditional magick around the age of fifteen, Crowley and other people.

MFU: You’ve said you don’t do cut up with words but mostly use pictures; how do you see pictures and words working differently in creating our reality?

GBPO: Pictures are less dogmatic; there are more interpretations. It’s almost like you can build worlds that didn’t exist. You can assemble them into a window on a world with different geometrical rules, different mathematics—you might see a whole other civilization or universe in each picture, and it can remind you that there are infinite options all the time. There is not a fixed point, no actual answers, it’s just a flux of possibilities to explore and sometimes share, and it might be of some use to somebody.

MFU: Do dreams play a role in your ideas and methods?

GBPO: A lot of pieces we make are from dreams. We see them finished and then we just copy them. Like my piece Touching of Hands (2016) which is just coming now out of Saint John’s Cathedral in New York. That is a good example of patience as well.

MFU: I like the idea of patience a lot. It’s something I’ve been thinking about.

GBPO: Back in the early ’80s we were visiting Brion Gysin in Paris one day. At some point he said to me, Wisdom can only be passed on by the touching of hands. Toward the end of last year we were asked by the Rubin museum to make a sculpture as part of our retrospective there, and we remembered that phrase and we were thinking how would we do it, and wouldn’t it be nice to have a cast of my hand in bronze for people to touch, so that it can get shiny where people keep touching it. When we were visiting a friend in LA I wanted to make a cast of my arm and my friend said, Oh I know a girl who does that, Sara. So she rang her up and she made a mould of my arm like I was shaking hands, and we told my gallery, Invisible Exports, and they found the money to have it cast in bronze. So then it was in the museum, and it said “please touch the sculpture” and underneath it on a plaque it says “Wisdom can only be passed on by the touching of hands—Brion Gysin” which was what, thirty years later?

MFU: I’m really interested in the role of intention in your art making.

GBPO: Well we don’t make it to entertain, and we don’t make it to sell it. We just refused to sell something actually—the Blood Bunny…

MFU: Well that is an object you can look at without knowing anything and see that it radiates a hologram of memory.

GBPO: Blood Bunny is a wooden rabbit, very crudely carved—it almost looks a bit demonic. Myself and Lady Jaye were in New Mexico and there was one of these stalls by the side of the road with all these carvings and this little bunny had been put underneath because it wasn’t good enough to bother to paint, and of course that is the one we wanted. So we took it back home. And when we were doing ketamine sometimes you can’t help it you just bleed. SO whenever we bled we’d just rub it into the bunny, and it’s what, 40% brown now? So it’s full of blood and ketamine. We used to call it Ketamina Cat, even though it was a bunny. Once we were doing a purification ritual with Jaye, we cut her ponytail off and put it on the bunny, so it’s got a long ponytail that is right down to the ground and that’s the Blood Bunny. It’s really very intimate and that’s why it isn’t for sale.

MFU: But you’ve exhibited it as an artwork.

GBPO: Yes. Well, in an art museum. I don’t know if it’s really an artwork, it’s more a fetish. That is most of the things we make, fetishes.

MFU: When you started showing them in art spaces was that weird?

GBPO: That’s where people want them isn’t it? Yes it still is, especially when you don’t know the people, because they’re all very intimate. Sometimes it feels kind of transgressive that people you might not want to have dinner with are looking at something that is that private. But at the same time, maybe it will change them a little bit without them even realizing it.

MFU: Is that the hope, when you talk about art sharing or transmitting knowledge by you putting these things in spaces? Whatever nugget of wisdom is able to make it out to others?

GBPO: That’s the hope. It’s getting difficult because certain things have been sold, and that makes it hard to do another one because you don’t want to make another one just because it might get sold.

MFU: You mention time is energy, can you speak a little more about that? And how it interacts with patience, and do you see that energy is like a force?

GBPO: It’s more like an electricity; it’s like gravity—one of those energies, and time is actually among them. If its an energy, then by using things that we’ve had for along time it feels like they’ve actually absorbed that energy of time and everything that happened during that time is in there. Like hair—we use hair a lot—because its a measurement of the whole time you’ve been alive, like that ponytail on the bunny, it’s got that whole measurement of Jaye’s life in it, somehow. We use hair a lot for that reason. When we first decided that we were really going to just commit ourselves to each other 100% we shaved all the hair off of our bodies and put on diapers and pretended we were newborn babies. We had no time on us and whatever grew back would just be our time together. Jays used to keep all of it, sweeping up hair out of the beauty shop and finger nails, all of it. I always give people hair if they want it. I say, Magick defends itself, you’re not going to get at me with that bit of hair. It’s all about intention and belief. With Jay it was more that it was parts of us that contained our DNA that might come in useful, and it has as it turned out. There is one piece we made Alchemical Wedding—we met this artist who blows glass and made us these three spheres and we put Lady Jaye’s hair, fingernails, public hair, etc., in one, and mine in the other and mix them in the middle.

MFU: Without having a formal education in art or music, how did you teach yourself how to write songs and make music? Did you imitate greats to learn how they did it?

GBPO: No. I don’t know how to play anything. I don’t even know how to tune a violin, but I play it nearly every night on tour.

MFU: So how did you learn to play?

GBPO: I didn’t learn, I just did it. I just thought, this sounds alright and this doesn’t, that’s a bit boring let’s put it through an echo deck. Where’s a fuzz box? It doesn’t really sound like a violin in the end, it just sounds like a strange cacophony. I now play it with two bows, on a stand and just saw at it. I’ve never learned to do anything, and it’s never held me back. With Throbbing Gristle it was the same as everything else: Ok, we don’t want to do Rock music—what do rock bands do? They have a drummer that plays these traditional 4-4 riffs etc, so—No drummer! Get rid of the drummer. Ok, what about the guitarist? What do they do? They always play these riffs so we need someone who can’t play guitar at all. Cosi, you hate guitars right? Yeah! Ok you’re the guitarist! Then we went to Woolworth’s to get the cheapest guitar we could find for fifteen quid, and she said, it’s too heavy. So we got a wood saw and just sawed off the extra wood so it was lighter, and that was her guitar in TG. Chris made his own synths at home and Sleazy used tape recorders. Somebody had left an old base guitar, and we had no strings or pick-ups or anything, and Chris by accident put lead guitar Humbucker pick-ups in it—the wrong ones—and we bought jazz strings by mistake, so it had this really interesting sound, and again I put it through echo decks and played it with leather gloves on, so I couldn’t make it sound right. We thought, now we cannot play any music that normal people could play, lets see what we can play, and we started to jam every weekend. Just like we used to dress up every Friday, Saturday and Sunday and play. We built our own speakers and PA. And then we’d copy it until we had about an hour more or less where we could get that kind of sound and that was the first gig, we did that. Then they decided they wanted me to try and do vocals and we’d just been reading a book about Ian Brady and Myra Hindley so the first song was about them. Ian Brady and Myra Hindley—Very friendly! That was the chorus. They were serial child killers in England. We wrote that on the spot.

That is what became Industrial Music, the result of all those jams. We thought we had to give it a name, and I eventually came up with “Industrial Music” on September 3rd 1975 in London Fields Park, Hackney, talking to Monte Cazazza. I said, it’s got to have a name, this music. He said, you keep saying that word “Industrial,” why don’t you call it “Industrial Music” and it doesn’t sound anything like what we were doing, but that’s alright. It mutates. We’re an unusual case. Like we did with the characters, strip it all away and see whats left: that must be it. And also we didn’t’ want to sing with an American accent like the Stones, so I sang with a Manchester accent which is what I had, which also hadn’t been done much at the time.

MFU: I think a lot of problems that people have in making art is there is a filter of judgement that comes into it, like oh this is not very good, or this is what it means that I’ve done this. It feels like you totally removed that kind of judgment.

GBPO: Yeah, we played for a year before we played in public. And the first thing we played, we played from behind a wall. We closed the doors and played inside another room so people had to listen through the wall, which sounded great because it was vibrating concrete. We did all kinds of things like that. We did another one at the architectural association where we built a big cube out of scaffolding and covered it with tarpaulins and planks, with speakers on the ground outside pointing up but it was in a courtyard and the only want hear up with to go up to the roof and listen, but then you couldn’t’ see us. We had cameras inside that went to TV screens with no sound, so you could either watch us play or listen to us, but not both. There was a riot—they smashed the doors to get into the courtyard and threw things from the roof, including a toilet. They went crazy, because they didn’t like the idea that they couldn’t see us perform while they listened. We did another one where we performed behind huge mirrors so they only saw themselves. We did one at the filmmaker’s coop where we played behind the screen. People threw chairs. It’s amazing what you find out about people’s need for a formula.

MFU: I’m thinking about Lady Jaye; can you talk about any of her beliefs or wisdoms that really inspired you to fall in love?

GBPO: Well you know the story if you saw the film. She is the biggest influence on everything. She was already a priestess of Oshun in Santeria when we met. So she introduced me to Santeria. When we met we just really wanted to just be absorbed into each other. We’d never met anyone else who just got it—the total commitment—without any sort of hesitation. Her favorite saying was, see a cliff, jump off. She was the one that came up with the idea of the “of course” factor. Like, the voodoo priest says to me that I have a dead twin and I’m wearing her earrings. Jaye would say, of course. How to explain it, she’s a great catalyst really. There was nothing we could do or say that would cause her to hesitate, she’d just say, ok let’s do it. It was a constant recommendation to push further. She’s just present in everything isn’t she?