Pageslayers lays down literary roots in the Opa-Locka community

Andrew Boryga

Not long after this initial spark, De Greff became a Knight Arts Foundation Grant winner and PageSlayers, a series of three, two-week-long creative writing summer camps in Opa-Locka, was born.

De Greff said her mission, like that of other programs in the city such as The Sun Room in Liberty City, is to help close persistent gaps in accessibility to the arts. The global success of Art Basel, rise of art galleries and colorful murals in Wynwood, and enduring success of independent bookstores, like Books and Books, speak to a vibrant artistic community in Miami. But like other large cities, the opportunities for children and young adults to engage with the arts are often limited to those with families that can afford to live in pricey neighborhoods, attend events, and plunk down hundreds, if not thousands, on lessons and workshops.

De Greff decided on the city of Opa-Locka for its need—close to a third of residents live below the poverty line—but also because the Moorish arches and domes adorning many of the administrative and government buildings there take design cues from the 18th century collection of Middle Eastern folk tales One Thousand and One Arabian Nights. “A city in Miami based on a book? It’s so strange and cool,” De Greff said. She subsequently partnered with the OLCDC, a non-pro t community development organization in Opa-Locka and creators of the Thrive Innovation District, a hub of free arts and crafts activities and career services for the Opa-Locka community.

On the very first day PageSlayers launched in June, I was one of two workshop instructors standing in front of a smiling group of fourth and fifth graders who were eager to get their hands on clean notebooks and sharpened pencils. Our classroom was located in the central office building of the district, surrounded by a motley of creative pursuits. In the room to the left was a dance studio. On the right, a room full of audio and production equipment kids used to create beats that sometimes caused our class, instructors included, to stop cold and nod. Down the hall kids built their very own apps and websites.

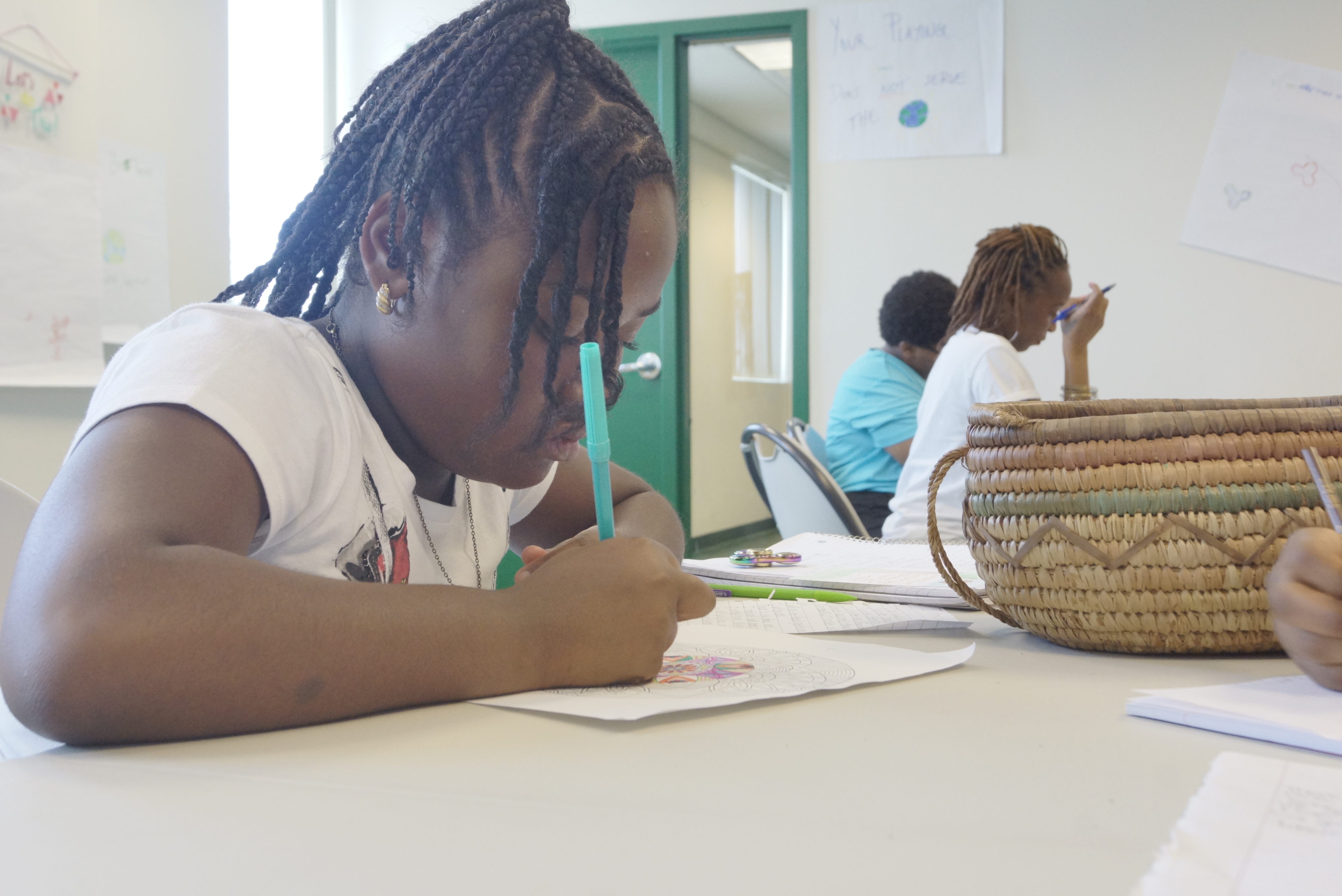

In our own creative writing workshop, we talked about what it means to create images with words and read the poetry of Elizabeth Alexander. It didn’t take much prodding to get them to start creating their own images.

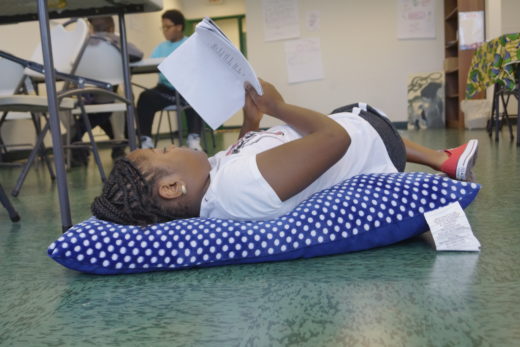

This enthusiasm was constant in the classes I taught, and others I visited periodically over the summer. Each workshop session started at 9am, but kids knocked at the door by 8:30, anxious to sit on the carpet in the front of the room with pillows and books. Many came to us as already burgeoning artists: One camper had multiple screenplay ideas in the works and another was halfway finished with a novel. As I stood at the front of the room one afternoon early into our session and tried to explain how a metaphor worked, a small, spunky girl with frizzy hair named Jamiya raised her hand and said, “Mister, we know this already.”

Mostly, our job as instructors was to expose our students to different forms of writing from authors who wrote about people who looked like them. We read poetry by Ross Gay and U.S. Poet Laureate, Juan Felipe Herrera; fiction by Sandra Cisneros and James Baldwin, and a graphic novel about the baseball player Roberto Clemente. The different genres and forms we sampled spoke to different students. Some became infatuated by the punch of poetry, like Paola Delva who wrote about the importance of respecting what others have to say, no matter how young they may be:

We have voices that

Need to be heard.

So you can all see what

We have done to inspire you.

Other students preferred longer prose, and still others found it easier to keep the words spare and tell stories with drawings and short dialogue bubbles, such as Corinthia Small who created a graphic novel about a young girl named Cori who is afraid to act but ultimately overcomes her fear by stepping onto a stage and wowing an audience at a competition. “Did I just do it?” she asks herself in one of the frames, her eyes bulging wide.

Over the course of the summer, our students began poems with forward-thinking lines like “In 2081, everybody was equal.” They turned Walmart into an adventure setting; they wrote exultant odes to their fidget spinners and iPads, and they created a superhero named Lloyd who wore a ninja suit, lived in a secret lair and—when he wasn’t watching TV—wielded the “ ve elements” of the earth to defeat his enemies: water, re, ice, earth, and lightning.

Many campers were children of immigrants from Haiti and the Dominican Republic and wrote about what it feels like knowing someone they love could be stripped away by immigration officers. They did not shy away from politics. One student used a poetry assignment to list the 10 things he imagined President Trump doing every day. Number two on the list was “Plot ways to remove Obamacare.” Number ten was “Smile at my wig.”

In addition to daily lessons and activities, each session was visited by notable guests from the Miami artistic community who led mini-lessons. These included April Dobbins, a photographer, writer, and filmmaker whose work has screened at festivals across the country. After her presentation on the foundations of screenwriting and what life is like as a filmmaker, students lined up for her autograph and talked about writing and directing their own films one day. Then there was the poet Dru Phoenix, member of a collective of military veteran performing artists known as the Combat Hippies. Dru arranged students into a circle and used his expertise as a performer to teach students about making an emotional connection with an audience when performing their work. His lessons came in handy during the last half an hour each day, which was often set aside as a poetry slam/dance contest/talent show. Students ran the event themselves, arranging chairs in the room into a makeshift theater and performed under self-appointed monikers like Zen Master, the Cheese Dad, and Water Boy MLG.

The very first special guest to visit was acclaimed novelist and Miami resident, Edwidge Danticat, who joined my class one morning, kicking off her shoes just like our students did whenever they entered the room. Danticat led exercises about structuring stories and creating compelling characters. Afterwards, she answered important questions the students had for her: How long does it take to write a book? How much do you get paid? Who gets to design the book cover?

When I spoke to Danticat about the experience, she championed the mission of PageSlayers. “It’s unfair that so many kids in our community are lacking so much that other kids take for granted,” she said. “All kids should have wonderful programs like this on a routine basis.”

I and other instructors in the program found ourselves repeating the same thing in conversations with one another. As a child growing up in the Bronx, I attended public schools until high school and was blessed to have many teachers who took an interest in me, and steered my hunger and drive to become a better writer. But it wasn’t until much later on in my life, after I was fortunate to receive access to exclusive educational programs, attend an Ivy League university, and become introduced to writers of color outside the much begrudged Anglo-dominated literary canon, that I realized it was even possible to turn my creative pursuits into a career that could be fulfilling, challenging, and even pay my bills.

Too many students in our country never have the chance at this sort of awakening—particularly students of color. African-American and Latino students are half as likely as their predecessors in 1982 to receive arts instruction in school despite evidence that such exposure improves academic performance and attendance. Meanwhile, the Trump administration has put the National Endowment for the Arts on the chopping block and the latest budget calls for nine billion in cuts to school fundiing. In such an environment, programs like PageSlayers will become increasingly vital to lower-income communities.

At the end of the summer, all of the students in the building, ranging in age from 4th grade to 12th grade came together to participate in a showcase in front of family and friends. Students from our three PageSlayers sessions performed the work they’d produced in their workshops and presented the individual zines they’d created with the help of local artist and print shop owner, Ingrid Schindall. One camper, who liked to be called Jazzy, said it was the happiest day of her life because she got to share and perform her work, but it was also the saddest day because the program was over.

Most PageSlayers students seemed to echo this sentiment. At the start of the summmer, De Greff and even instructors including myself, worried that two straight weeks of sitting and writing, and talking about writing would get tiring for an eight year-old. It even gets tiring for me sometimes, as an MFA student. But in class surveys and in teary hugs on the last days of camp, almost every student wished they could stay with us longer.

On one of the last days of my camp session, I pulled a wiry boy named Avery aside and asked how he felt camp went. He was dubbed our “class novelist” because he was famous for writing entries in his book that were two or three times longer than what everyone else wrote. “I like this camp because we get to write and read what we wrote. Also we get food,” he said, referring to the free breakfast and lunch each camper was provided every day. When I asked him what he’d be doing over the summer if he wasn’t with us, he twisted his foot and thought about it for a while, then shrugged. “Probably be home for like seven hours watching television or playing video games.”

I asked where he’d rather be. He smiled and said, “Here.”

Andrew Boryga is a writer based in South Florida. His work has been featured in The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Atlantic and other outlets. He is a Michener Fellow in the University of Miami’s MFA program.