- The Justification of Modernist Painting: A Review of Frank Stella: Experiment and Change

- Dale Zine Miami: Mall as Community as Art

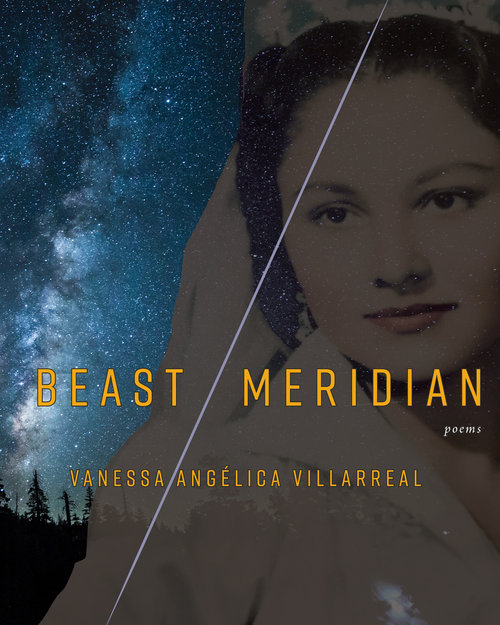

In the wildness of daughterhood: Beast Meridian by Vanessa Angélica Villarreal

Zaina Alsous

Noemi Press, 96 pages

Noemi Press, 96 pages

Born in the borderlands of the Rio Grande Valley to formerly undocumented Mexican immigrants, Vanessa Angélica Villarreal’s syntax blends English and Spanish, memory and dream, distance and intimacy, to cultivate a powerful meditation on the tensions between Outside and Inside. “I hunt the wilderness in myself stalk the tall grasses I am she who betrays blood for a little bit of kingdom” (from “Malinche”). This “wilderness” can be understood in the daily alienations faced by working-class immigrants in the U.S., escalated when additionally navigating queer sexual desire, feminized gender expression, and inherited traumas. But this wilderness is also a space of the yet to be colonized, a site of imagination and resistance. Rather than appealing to whiteness or innocence, Villarreal digs deep into her complex and state-despised subjectivities with stunning sensuality and inventive form.

Using footnotes to subvert notions of citable sources, Villarreal amplifies the role of canonized psychology texts in pathologizing, and often criminalizing, young immigrants and people of

color. In the series “Assimilation Rooms” Villarreal demonstrates how the power wielded to define sanity and mental competence can often mirror colonial projects to “civilize” populations deemed out of control: “INCIDENT: Nothing / an immigrant’s daughter does / is intelligible.” Villarreal’s poems imaginatively connect the corporeal to the land, in speculative gestures that expand the narrative of assimilation beyond its clinical designation, tenderly evoking her own struggles with psychological trauma: “a daughter bound by trouble / is a wilder grief / manifested bodily / oilthick stars pour down their / vines.”

Sprawling across pages or written in concrete blocks with precise gaps, many poems in Beast Meridian read as wounded maps, or fragments of incomplete histories; the collection even includes faded pictures of her family members. Villarreal’s poetry is often fearless and avant garde but makes room for nostalgia, “join hands with / the invisible / the disappeared / the forgotten / river flooding / the land nourished / the blooming mourning / the return of the beasts.” The effect is like looking at an old photograph, mediating the distance between memory and a swell of feeling.

Villarreal, a self-described “first-gen grunge rgv htx xicana / hybrid poeta bruja / USC PhD+mami” has written a collection of testimony and reverence for the women who came before her, particularly her grandmother who died at fifty from cervical cancer, and who shares her middle name, Angélica.

Beast Meridian also functions as a much-needed critical refusal to flatten any of her identities to fit within a contained geography. As visual artist Wangechi Mutu once shared in an interview with Art on Paper magazine, “Females carry the marks, language and nuances of their culture more than the male. Anything that is desired or despised is always placed on the female body.” Villarreal’s poems carefully and boldly draw wider horizons for this body, inventing a new space where daughters, particularly daughters of diaspora, can be spectral cosmology, rather than digestible stereotype or silent victim. Melancholia, grief, the spectacular violence of living within a society that hunts and tames non-white women, destroys but also creates new meanings.

Under the dark haze of Trump’s vitriolic rhetoric, and daily attacks on immigrant communities, Villarreal’s poems manage to sing out from the graveyard, from the detention centers, from the vines. In “A Field of Onions: Brown Study,” dedicated to “the immigrants buried in mass graves in and near Falfurrias, Texas”, she writes, “We the holy, are never really still. Agitation pulls even at hanging planets.” Somehow her poems gesture that for us daughters of immigrants, part beast, part estrella, there still exists an elsewhere, a radiating solar system, yet to be broken and conquered.

Zaina Alsous is a writer, editor at Scalawag Magazine, and grad student at the University of Miami. Her work has recently appeared or is forthcoming in The Boston Review, The Offing, Anomaly, and The New Inquiry.