“I’M HARRY SMITH AND I HATE YOU!”

KEVIN ARROW

Harry Smith with this “brain drawings” (ca. 1950). Photo: Hy Hirsh, courtesy of Harry Smith Archives

He was known to spend years working on a single labor-intensive film only to unspool it down Second Avenue in New York’s Lower East Side in an alcohol-fueled temper tantrum. Artworks and collections have been given away or lost as he was evicted from the various hotel apartments he inhabited during the decades he lived in New York. He survived by selling, trading, and bartering his artwork for food and rent.

Toward the end of his life, Smith was the “Shaman-in-Residence” at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at the Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado, founded by Tibetan meditation master and teacher Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. At the Naropa Institute, Smith taught classes on alchemy, Native American cosmologies, and the rationality of namelessness, and was supported by a grant provided to him by the Grateful Dead organization.

I first encountered the name Harry Smith in the late 1980s in obscure music and enthused culture zines like Chemical Imbalance and Forced Exposure. These were two important outlets for learning about music, literature, visual art, and film inthe pre-Internet era and Smith was always written about with a sense of awe and reverence.

Early Life

Harry Smith claimed to be either the lost son of the Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna, daughter of the last Russian tsar who escaped assassination during the Russian Revolution, or the orphan of British occultist Aleister Crowley, depending on who he was talking to. Public records indicate that was actually born in Portland, Oregon. He was brought up in the Pacific Northwest by parents who were practicing Theosophists. Smith became interested in anthropology, music, and art at an early age. The Kwakiutl, Lummi, and Samish American Indian cultures permeated this region of the United States and by the age of fifteen he had already begun recording their songs and rituals and gained fluency in their spoken languages. During this time, Smith developed a taste for adventure, drinking, and mind expansion and spent a short amount of time in jail. He befriended Native Americans who, in 1964, invited him to record their songs and rituals, released by Folkways Records as a three-LP box set, The Kiowa Peyote Meeting (1973).

Around the same time that I first read about Smith, I found my first Bell & Howell 16 mm Film-O-Sound projector and discovered that the Miami-Dade Public Library’s main branch in downtown Miami housed an extensive collection of avant-garde films curated by Don Chauncey, then head film librarian.

Among the impressive holdings was a print of Smith’s Early Abstractions, which includes the shorts films 1–5, 7, and 10 (1946–57). I screened it privately and publically countless times.

Early Abstractions is compilation of short and medium-length hand-painted abstract exercises created using methods still not fully understood. They were made at the height of the San Francisco renaissance of the late 1940s and ’50s, when Smith began his lifetime obsession with fusing painting with enthused filmmaking. Surrounded by the masters of abstract cinema at the time, Smith was watching the films of Jordan Belson, James and John Whitney, Hy Hirsh, and Oskar Fischinger and he participated in the legendary Artin Cinema programs at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art organized by Frank Stauffacher. Art in Cinema’s programs were crucial to the emergence of the Bay area as one of the centers of independent filmmaking between 1946 and 1954.

New York Transition

It was around this time that his work caught the attention of Hilla Rebay, curator of the Museum of Non-Objective Painting in New York, which later became the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Smith was awarded one of the first Guggenheim Fellowships, which he used to relocate to New York’s Chelsea Hotel in 1951, finding the city to be a perfect environment to support his creative and intellectual life. He continued amassing his legendary collection of arcane and esoteric literature, pop-up books, Tarot cards, Ukrainian painted eggs, Seminole Indian patchwork, string figures, and found paper airplanes. At the time of his death, the collections were distributed among various museumsand private collections, while his papers are housed at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles thanks to Rani Singh, one of his last assistants. A collection of approximately two hundred fifty paper airplanes Smith found in the streets of New York over a roughly twenty-year period was donated by Smith to the Smithsonian Center for Folklife Programs and Cultural Studies. The collections of paper airplanes and string figures are the subjects of two recent catalogues raisonné edited by John Klacsmann and Andrew Lampert and published by J&L Books and the Anthology Film Archives (2015).

Smith became a scholar of numerous subjects and was skilled at conversing at length while intertwining compound topics. Many visitors reported that Smith’s room at the Chelsea Hotel was a Wünderkammer, neatly stacked floor-to-ceiling with his books, art supplies, and collections. Early in his career, he began collecting thousands of American folk, popular songs, and race records when early shellac recordings were being recycled for the United States war effort. Smith understood the importance of these recordings and hid them away. It was in 1953 that Moe Asch of Folkways Records released the important three-volume set Anthology of American Folk Music coordinated and curiously annotated by Smith. In the late 1950s and early ’60s, the Anthology fell into the hands of many musicians, which helped spark the folk music revival during that time. Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and Jerry Garcia all claimed to have learned songs from the Folkway’s Anthology of American Folk Music. These musicians went on to help change American culture and Smith said, in his acceptance speech for a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award the year he died, “I’m glad to say that my dreams came true–I saw America changed through music.”

Harry Smith’s Magnum Opus

Smith’s most ambitious and enigmatic project, Film no. 18, Mahagonny (“A mathematical analysis of Marcel Duchamp’s The Large Glass, expressed in terms of Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht’s opera Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny”) took ten years to complete and runs for two hours and twenty-one minutes. Mahagonny can best be described as abstract cinematic poetry that was made to be displayed with four separate 16 mm projectors onto a single screen or onto two billiard tables suspended over a boxing ring. Smith took years to dissect and study The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, a dark, political, and satirical opera composed by Weill to a German libretto by Brecht. It was one of Smith’s most rarely screened films due to the complexity of its timing and sequencing. It took two very patient and skilled projectionists to carry out the complicated presentation. It was only screened six times in 1980 at the Anthology Film Archives. The time-consuming and heroic effort to restore the film was spearheaded by the Harry Smith Archives. It had to be painstakingly pieced together and synchronized following complex notes and ephemeral materials left behind by Smith.

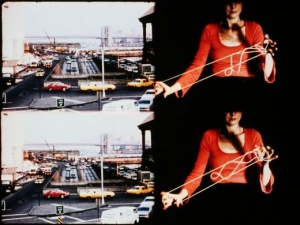

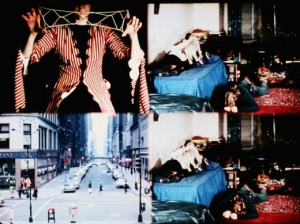

Harry Smith, Film #18 Mahagonny: A mathematical analysis of Marcel Duchamp’s The Large Glass expressed in terms of Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht’s opera Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, 1970–80. 16mm film, 2 hours, 21 minutes. Courtesy of Anthology Film Archives, New York

Some of the most beautiful passages of Mahagonny occur when Smith’s hands appear in the frame, manipulating various objects. Most often his hands are painted in a curious manner, with what appears to be red and green paint, and they are further enhanced by the effect of colored light. Other mesmerizing passages include when Kathy Elbaum, a colleague of Smith’s who had recently returned from a research expedition to Canada, appears on camera skillfully demonstrating various Inuit string figures and tricks, one after another in fluid succession.

All the actors in the film were friends of Harry’s that happened to be in the Chelsea Hotel. It is easy to identify Allen Ginsberg sitting in a chair, reading, while bathed in New York early-1970s sunlight, Mekas as a younger man, and a youthful and innocent-looking Patti Smith. These are epic cameos. The film also shows reoccurring faces who can perhaps be stand-ins for the characters in the Mahogonny opera: Fatty the Bookkeeper, Trinity Moses, Leocadia Begbick, Bank AccountBilly, and Alaska Wolf Joe, or they represent numeric equations referencing The Large Glass.

Mahagonny can be watched while considering that Smith was perhaps constructing a precise mathematical and poetic analysis of The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny that he believed to be the most important piece of music and cultural criticism of the twentieth century.

Jonas Mekas

While in New York, I met with Jonas Mekas, the ninety-three-year-old filmmaker and founder of the Anthology Film Archives at his studio in Brooklyn to discuss Smith, Mahagonny, and the scene surrounding Smith at the time. Mekas has been watching films, writing about films, making films, and living films for longer that you can imagine. He was living and breathing and filming in the midst of the Velvet Underground’s first appearance, Judith Malina and Julian Beck’s Living Theater,the birth of Fluxus, Andy Warhol’s Factory, John and Yoko’s bed-in for peace, Cunningham, Cage, and Kerouac. It was as the founder of the Filmmaker’s Co-Op and Anthology Film Archives that Mekas first encountered Smith. He was once asked about their first meeting and, as I recall from the account in the book American Mag us Harry Smith: A Modern Alchemist, Mekas described it as something like this:

Harry Smith walked in—I had never met him before, this was in 1962—I thought that he was sixty or seventy years old. ’I am Harry Smith and I hate you!’ he said. I said,’Harry, you don’t know me—do you know what it means? You are saying that you hate somebody?’ And I looked straight at him and said again, ’You know what you are saying?’ He looked at me, turned around, and walked out.

Smith proved himself to be irresistible to Mekas for the remainder of his life. Harry Smith practiced magic. I sat down with Mekas to discuss all this further.

KEVIN ARROW (MIAMI RAIL): The whole idea of Marcel Duchamp, mathematics, and The Large Glass sideswipes everything—I was trying to wrap my head around Brecht and Weill and was then trying to decipher the Duchamp reference and I don’t even know where to begin.

JONAS MEKAS: That’s Harry! That film is pure Harry. Don’t ask me about meanings!

RAIL: Did Harry ever say much about his films after they were made?

MEKAS: Whatever he had to say is in the Filmmaker’s Cooperative Handbook, he wrote the film capsules and didn’t talk much about his films.

RAIL: Is it true that people may have been intimidated to organize events with him to show his films?

MEKAS: He refused to go. I don’t know a single case when he would have accepted to appear after a film, but his room was always full of friends at the Chelsea Hotel.

RAIL: So he was good in informal sessions—would impart his knowledge to people?

MEKAS: No, he wouldn’t talk much, he would usually just insult them — he was not lecturing. He was a man of few words and would easily snap. They are a few recorded interviews with P. Adams Sitney. He also wrote a lot and he left behind a lot of scribbles.

RAIL: Regarding the film restoration project, who instigated the process?

MEKAS: The Anthology Film Archive has all his films, we are the only ones doing it, and not everything is preserved, because of money limitations.

RAIL: Apparently the right date and time and combination of factors arose and investors appeared?

MEKAS: Yes, but unfortunately they did not want to spend money preserving the individual films [of Mahagonny]. They wanted to put it onto one film, which was the wrong idea, but it’s OK.

RAIL: Are there additional films out there awaiting this same kind of a treatment?

MEKAS: They are all preserved except for the original materials for Mahagonny, we would need close to one hundred thousand dollars to do that.

RAIL: It does seem as if someone ought to do a frame-by-frame analysis of Mahagonny, if that is even possible.

MEKAS: Yes, that is the future.

RAIL: There is a 16 mm print of Early Abstractions in the Miami Dade Public Library, which I have watched countless times, and I have the Mystic Fire VHS tape as well. I am fascinated by themethods Smith employed to screen these films publically, in which he used slide projectors and was manipulating the images with crystals…

MEKAS: And colored gels.

RAIL: I understand that he used large lanternslides, some of which are reproduced in the book Experimental Animation Origins of New Art,by Robert Russett and Cecile Starr.

MEKAS: Yes, that projection instrument machine Harry destroyed. He made it himself. It was a contraption that you could take apart and put together and place a projector inside of and there was another place for different sized and shaped gels, and as you project you could do all those tricks. This was made especially for the film Heaven and Earth Magic (1962). Not for Early Abstractions, which was always shown straight, with no manipulation.

RAIL: I have Heaven and Earth Magic as released by Mystic Fire on VHS and it’s only in black and white. So when Smith presented this live, there were colored passages?

MEKAS: Yes. And you know, his paintings have yet to been seen and exhibited. We are currently trying to build a library, performance space, and a Heaven and Earth Cafe on the roof of the Anthology Film Archives. It will be for books, periodicals, and documentation and a lot of Harry’s art and paintings.

RAIL: So this is material that didn’t go to the Getty?

MEKAS: Most of his materials that have to do with music are at the Getty, and someof the paintings that came from individuals, but most of his paintings he left with me, which I deposited at the Anthology, but since we are not a museum and cannot care for them, we are selling them to build the library. We have forty Smith paintings, which we are selling for ten million dollars, which I consider to be the cost of one second-rate Warhol! With forty paintings from Harry Smith, we will build the library and the café, because we are really suffering right now and half of our paper materials are in boxes and we have more coming in, and since we are operating on a deficit, the café will help us break even, at least. So, I am forced to sell the paintings to build the library. The paintings have to be purchased and kept together–some foundation should buy them and deposit them in a well-established museum.

RAIL: I often tell people that Harry is the most important twentieth-century artist that you have never heard of.

MEKAS: Some people who know Harry’s work, like Henry Geldzahler, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, he thought he was a much more important artist than Warhol, as a painter.

RAIL: I am sure Harry would have something to say about time cycles and that there needed to be this much time to pass before people would wake up and pay attention.

MEKAS: That is exactly what Henry told me, that he has to die and then people will eventually understand his work and he will be evaluated in the right way.

Kevin Arrow is an artist and museum professional living in Miami Beach.