Life on the Porch of the Cardozo Hotel

Jack McClintock

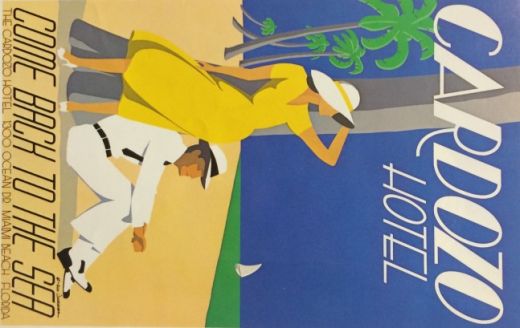

The original illustration for this piece, a poster designed by Woody Vondracek.

For all its regular crowd of artists and writers and creative hangers-on, the porch still isn’t Soho, or Greenwich Village, or even Coconut Grove. But it isn’t Hialeah, either.

“IF I DON’T FIND AN INTERESTING JOB OR A WONDERFUL WOMAN SOON I KNOW I’M GOING TO BUY A CONVERTIBLE.” —OVERHEARD ON THE PORCH OF THE CARDOZO HOTEL

The first thing you see at Thirteenth and Ocean Drive is not the porch itself, but the hotel, the Cardozo. It is an art deco building—one of 800 inside Miami Beach’s art deco district—with lidded windows, rounded corners and a streamlined look. Someone once described it as looking like a big, pink toaster. With the other 799 deco buildings, the not-quite fifty-year-old Cardozo has been placed on the National Registry of historic Places, largely through the efforts of Barbara Capitman’s five-year-old Miami Design Preservation League.

Capitman’s son, Andrew, and a consortium of investors operate the Cardozo along with six other art deco hotels. The Capitmans’ achievements have delighted many people, most of whom are content to love the hotel and its porch for their playful charms. A few of them have become full-fledged deco buffs, who can be found on the porch at any hour discussing art deco, which through verbal wear and tear has become the second dullest topic hereabouts. (The dullest, also through overuse, is a religious leader referred to by his proselytizing followers as The Perfect Master and by one less admiring porch visitor as “a fat little moon-faced kid with a wispy mustache.”)

Both the Capitmans seem to like and admire artists, despite the notorious ingratitude of some of them, and from the beginning have encouraged their presence on the porch. At first, the porch was nothing more than a lineup of aluminum chairs, occupied about equally by elderly people who lived in the hotel and young people who came by to see what was happening with Barbara Capitman’s MDPL, located for awhile on the first floor of the Cardozo. About a year ago, the hotel café opened up off the porch. Artists and writers and other creative types in need of modest rents began to move into the rooms upstairs. For reasons that are never fully clear in these matters, new people started to show up.

Woody Vondracek was one of the first. He came to Miami a few years ago to escape assembly-line life in Detroit, decided to teach himself to be an artist, miraculously did so, and fell in love with art deco—which is his own style now. Woody spends a lot of his social time on the porch. He likes to say, “What is there to life if you can’t have a porch where you can drink a beer, smoke a cigarette and hang out with the guys?” He grins at this, since he’s said a lot less than he means. From a corner table, Woody surveys the passing scene: artists and gallery people, writers, poets, dancers, photographers, cinematographers, architects, professors, editors, art directors, film producers, an occasional political gifted with artistic or humanitarian sensibilities. “They’re coming back to the sea, I guess,” says Woody, grinning again. Inside the hotel, in the lobby, is the poster Woody designed for the early days of the Cardozo’s rebirth. Across his customary stylized deco images are five words: “Come back to the sea.”

On the porch these days, there is an eager, innocent, provincial, youthfully earnest near-sophistication that is touching, and very rare in South Florida. It is a little like Key West, where something always seems about to happen, but without the world-weariness and weird hard edge of antic desperation. For a clientele whose interests lie in the arts, the porch is maybe all Miami has left in the way of a place to sit and have a drink and watch the people and see who shows up.

Someone always does. In addition to the locals, there is an interesting mix of out-of-towners. One night, a poet from Oxford University. Another time, the director of famous pasta westerns. The star of a television sci-fi series. An award-winning documentary film producer. The theater critic from The New Yorker, Mikhail Baryshnikov. Well, it turned out not to have been him after all, merely a noble-headed fellow with skinny legs and pale, narrow feet in cheap rubber thongs. But for a moment there, everyone on the porch thought he was Baryshnikov. Which gives you an idea. The porch isn’t Soho, or Greenwich Village in the old days, or even Coconut Grove in the old, old days before that village gave up all artistic pretension to become a shopping center. But it isn’t Hialeah, either.

“ALL THE MEN IN MIAMI WEAR GOLD CHAINS. YOU CAN TELL A GAY ONE IF HE’S WEARING PEARLS.”

—OVERHEARD ON THE PORCH OF THE CARDOZO HOTEL

The porch looks across Ocean Drive traffic—passing cars and bodies sometimes give a strobelike effect to the view—to a broad, newly filled beach, with a breeze, and palms, and a blue ocean, and sailboats. In the evening, there are the stars and a moon snaking its silver track across the waves. You may even get ocean liners, streaming past on the horizon for your romantic bewitchment while you nurse the insipid American coffee and dreadful acidic wine that are the twin hallmarks of artistic hangout everywhere. (Thus proving that artists are not so effete or tender-tummied after all. Never met a painter or writer who couldn’t outdrink a truck driver, coffee or booze, name your poison.)

The porch stretches across the front and down one side of the Cardozo. It has a terrazzo floor; about 100 wooden chairs, made in Yugoslavia and upholstered in red leatherette; and some 25 linen-covered tables with legs of uneven length, most being propped level by folded matchbooks. There is not only linen on the tables, but fresh-cut flowers. The mustard is Grey Poupon. Someone is trying.

At the south end of the porch is a clattery array of aluminum chairs, occupied exclusively by the old people who live in the hotel. Despite the fact that they spend as much time on the porch as the “porch rats,” the regulars, the old people do not generally mix into the activity surrounding the tables around the corner. Nor do porch rats make any effort to draw out the old people. The old people know that some unacknowledged law has identified them as the wrong sort for the new Cardozo. One of the once said, “They’re trying to push the old people into the ocean.” But they’re not. The truth is, they’re only trying not to see them.

Among the regulars, gregariousness is the way of the porch. People are always meeting there, arriving for a rendezvous, being introduced there, or making contacts that will later be used for one purpose or another, or forgotten altogether. If you feel like talking, there is almost always somebody to talk to who is associated with, or at least peripherally interested in, the arts. Most of the time, there is an empty table to sit at and read a novel or The New York Times. On Sunday mornings, there may be a communal Times if you arrive early enough (do not swipe sections). And if it’s really early enough, and she feels like it, there will be fresh scones homemade by an artist named Lisa. On lazy afternoons, with a cool breeze blowing off the ocean, there may be a fellow off in the corner on the porch, coaxing a lovely Carulli rondo from his guitar, each note a perfect expression of something fresh and clean.

When people get bored on the porch, there is always something else to do. Unlimber your camera and shoot 36 exposures of the person across the table. Introduce Rolf, the handsome, virile, German male model, to any woman and watch her eyes. Eavesdrop. (From an attractive woman in her 30s to a tableful of men a few years older, after she had caught them all staring off the porch: “Tell me, I really want to know, what do 40-year-old men see in these beautiful 14-year-old girls?” “It’s just pure, abstract, aesthetic admiration,” answered one of her companions. “Will you buy that?” Interrupted another of the group, writer Phil Stanford, “Because these young girls are achieving maturity at just the same time we are.”)

Go upstairs to someone’s room and have a smoke. Stroll across Ocean Drive and sit on the coral rock wall and stare back at the people on the porch. Have a swim, taking care to protect any impulsively divested clothing from the outgoing tide. Lie back on the sand and watch the moon rise over the water or the sun set over the art deco hotels. (Deco is not dull to love at, only to hear about all the time.) Toss some deserving fellow into the ocean, or fantasize about doing so. Sit in a sports car around the corner, necking and drinking champagne. Bay at the moon, or otherwise behave…oddly. There is always something else to do, and the regulars on the porch tend to be the sort of people who will do it, whatever it is.

One day, a tall and striking brunette in white pants pushed back her chair and left the porch. She strode across Ocean Drive into the park, where a workman had just finished painting all the benches a fresh and glossy green. Deadpan, she sat down on one. An old woman passing shouted, “No, dollink, no,” but the brunette kept going deliberately to the next bench, a little smile on her lips now, and sat down again. Then she stood and bent and looked behind at her pants and went to a third bench and sat there too, the horrified old woman still shouting,“Dollink, no, NO.” Then, the brunette stood up and grinned widely, having apparently achieved just the pattern of horizontal green paint stripes she wanted on her clean, white pants. She waved cheerily at the stunned old woman and strode smiling back to the porch, where she finished her wine.

One night about eleven, State Senator Jack Gordon was sitting on the porch talking with his campaign coordinator, Susan Vodicka, and Diane Camber of the Bass Museum, and Lynn Bernstein of the Miami Beach Development Corporation, and Todd Bernstein of Hank Meyer’s PR firm, and some others. Gordon was discoursing in his cerebral and quietly charming way about how to get more artistic people active in his re-election campaign. It was fairly typical porch talk. What Gordon didn’t know, hadn’t noticed, was that something else typical of the porch was going on over his shoulder. From the semi-dark, half hidden behind a column, one could see the black, smouldering eyes of the Haunted Hindu. Beyond him, the recumbent lumpish form of a bag lady could be recognized on a bench across Ocean Drive.

As often as it may seem otherwise, the real characters of the Cardozo milieu are not on the porch but off of it, just across the railing—on the other side of the bars, as it were. The porch is simply a place to sit and watch the Haunted Hindu (who himself watches; he is a silent, swarthy man who just stares),The Woman Who Knows Who Shot JFK, The Woman Who Has Not Discovered the Wheel (so named because she tows belonging along the sidewalk in a cardboard box), Electric Bob, The Reader, The Maracas Man and the Guardian Angels. The Guardian Angels like to line up and count off before going inside for soft drinks, as if the porch were the canteen in a basic training camp.

It is not known whether the off-porch regulars have names for their counterparts on the terrazzo. But, democratically, the porch rats could be named as well. They include the Intense Comedian, the Virile Skinhead, the Abstracted Politician (not Jack Gordon), the Pain in the Ass, the Body Parts Man, Droll Pedro, el Borracho, Tintoretta, the Hawk, Mr. Perfect, C.C. Wilder, the Folk Hero, Marathon Man, the Bag Lady, Ms. Mango, Photomagic, Twister, the Blown-Out Broad, the Outrageous Faggot, the Ailing Artist, the Neon Lady and the Rampaging Opinionator. Continuing character types are a shifting cast of Waitrons, Metermaids, Knock-off Artists, Premmies, Irrelevant Suburbanites, Yalies, Deco Buffs, CPAs, Dope Dealers and Blocked Writers.

A journalist from up north has mentioned that every time she’s arrived on the porch she has found writers there, not writing. Which does not mean that they were blocked, of course, merely resting their insights. Or working up to a final statement on the distinction between movie reviews and film criticism. Or waiting for Godot. Despite the number of writers who turn up on the porch, however, there’s rather little literary talk. Even on the day when three writers discovered they were all re-reading James M. Cain that week, a fairly astounding coincidence, the lit-chat when not much farther than shared interest in Cain’s use of the word “uptight” in 1934. Writers never talk about writing anyway; they talk about agents, contracts, and how to get rich in the movies.

What gets talked about on the porch among writers are matters of authentic importance, such as who is wearing the tackiest Hawaiian print shirt. This got to be quite a contest for awhile. I thought I’d won hands down with a shirt that visiting Sports Illustrated writer Rick Telander acknowledged as “the most tasteless” shirt he’d ever seen. But then Phil Stanford—who was a barefoot surfer in Hawaii for a couple of years before he began writing for the New York Times Magazine, and being a political activist, and a private detective, and country songwriter, and all the other things he was—Stanford started showing up wearing an entire series of sleazy Hawaiian print shirts, for which he claimed to have paid exactly $1.79 apiece.

Stanford thought he’d won hands down, and would have, if it hadn’t been for John Rothchild. John’s non-fiction about Florida is as wise, and wry, as John D. MacDonald’s fiction about the same subject. He’s under contract to provided a book about the state to Viking, so he’s not around the porch so much anymore, but it was Rothchild who laid the shirt competition to rest when he turned up in a baggy, tacky shirt of one color and print, and a baggy, tacky pair of shorts in another color and print, and then pretended he wasn’t even trying to compete.

Clearly, this is not Algonquin-quality wit. These are not intellectual pastimes on the level of those among the Bloomsbury crowd. It was at the end of the shirt contest that Phil Stanford leaned back in his chair, shirtless, his hands behind his head and his elbows splayed, brow earnestly furrowed, and said, “The function of the porch is to make you so sick of it that you have to go to work.”

“I USED TO BE A NEWS JUNKY, BUT I GOT TIRED OF THE FOCUS OF MY LIFE CHANGING WITH EVERY DING OF A WIRE MACHINE. I’M A FEATURE KINDA GUY NOW.” —OVERHEARD ON THE PORCH OF THE CARDOZO HOTEL

The real artistic types on the porch are those who look as if they sleep on the beach under a palm. Sometimes these days, they are elbowed out of the way by people who seem to have come only to show off their new clothes from Mayfair, but even most of these are easily outdressed by the waiters. The Cardozo standard of snazz and flash is set by one waiter in particular, Flamboyant Freddy, who dresses in terrific high-waisted trousers, suspenders, Panama hats, and shirts that could stand up well against Joseph’s coat. Freddy has taken to art recently. He paints on seashells.

Despite his artistic interests, Freddy is a quick and courteous waiter, making him unusual on the porch. Ordinarily, service there is elusive. There is something ephemeral about the average waiter’s mood. One minute, he may manifest an inexplicable bright-eyed cheeriness; the next, he seems to be brooding explosively over some painful affront. More than one Café Cordozo patron has come away with the impression that this waiter was only fetching wine until called away to that dance company or premmie festival or saloon or gay disco which is truly his special destiny.

So, it is not the service which draws the crowd. Nor is it the food, since the kitchen is too small to allow much beyond microwaved simple fare or salads. The imported beer is good, and so is the espresso and cappuccino, when the machine is working. As this is written, the machine is not working.

Some days, nothing works, including the arrangement of people, and you wonder what draws anybody to the place. Frauds and pikers turn up on the porch, and mean-spirited authoritarians in hair pieces and three-piece polyester suits come to swelter and kvetch, who needs it? Some days, the porch seems an incestuous place where too few regulars have spent too much time. Some days, it’s just dull. One needs to get away, or bring others in. Sit at different tables. Get up and stretch. Make things happen.

Things happen, and in another week the porch has changed. Management turns over and waiters get sacked. The dance troupe checks out, so the slumped and sedentary writers lose the inspiration of their perfect posture. Phil Stanford moves to New York to become editor of a magazine. Another porch rat is evicted for not paying his bills, and yet another is banned from the porch for assaulting the paying customers with his religious convictions. One flies to the Virgin Islands with her dog. One goes sailing into a storm off the East Coast and is gone for weeks. A gossip goes too far, a confidence is betrayed, one couple splits up and another forms. Even the look of things is subtly altered day by day. Someone’s hair color changes. In an economy drive, Tabasco on the tables gives way to Frank’s Hot Sauce. The menu turns experimental. The espresso machine breaks down again.

It changes, the porch does change. The whole neighborhood changes. The Capitmans recently raised $6 million to restore all seven of their deco hotels over the next year or so, with new cafes, bars and restaurants. Evidently the new life on the Cardozo porch is only the first kickings of a South Beach deco rebirth—a coming back to the sea of lemming proportions. So far, only the wine has remained the same.

South Florida writer Jack McClintock lives in the Cardozo Hotel