End Game Aesthetics: Aramis Gutierrez

Shana Beth Mason

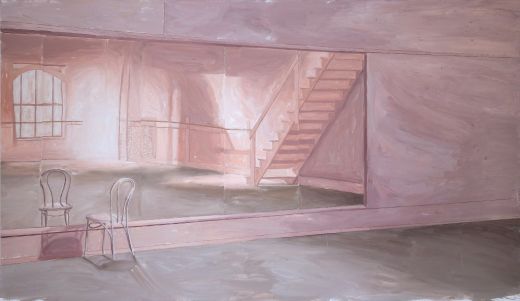

Aramis Gutierrez, End Game Aesthetics, 2012. Oil on canvas 72 x 125”. Courtesy of the artist and Spinello Projects, Miami.

Spinello Projects

It is potential energy, buzzing with doubt and hope, that describes the imagery of End Game Aesthetics, the new solo exhibition from Aramis Gutierrez. But while he maintains a comfortable distance from many of the historical events which inspired his works, he allows for painting itself to steer its viewer towards a reincarnation of the energies prior to, during, and directly following a ballet dance. These paintings convey a desire to move politically difficult and historically messy events to the forefront; the artist’s hand is still moved by the romance of dance, but it is not without the gravity of how the world of dance operates: commanded by borders, contracts, rivalries, and state secrets.

The exhibition is anchored by three large canvases, all charged captures of an empty ballet studio. The question of how the space is occupied is not as pressing as the politics of the space, itself. Gutierrez presents the dance studio as a type of mirrored theater: once inside, it does not immediately suggest the presence of invented characters, but invites the viewer to occupy two concurring dimensions. A large canvas in the first room, “Amedeo Amodio” (2013) is a dashing portrait of the celebrated dancer and choreographer, with an observant Russian officer seated in the background. Geopolitical implications tug at the dominance of Amodio’s own dynamics: he does not dance for the viewer, but is a candidate for selection. The painting’s physical surface commands greater prominence after the initial awkwardness of a passionate dancer and a stoic soldier paired together fades away. Gutierrez executes this effect perfectly: he retains the cultural, sociopolitical, even physical tensions between Amodio and his audience (it can be assumed the soldier is not there by himself) and does so with deliberate, elegant technique.

Making Love to Baryshnikov, 2013. Oil on canvas, 16″ x 20″

Smaller canvases are situated throughout the ground floor of the gallery. “Making Love to Baryshnikov” (2013) offers a cropped glimpse of hands raised upright in a hauntingly blue library room; the sweetness of lovemaking is intensified through the shades of blue and the woman’s anonymity. It treads the thin line between romance and erotica. “The Reward of Faith Is To See What You Believe” (2013) and “After No Exit” (2013) appear as tiny dioramas of dimly lit stages where a sole dancer seemingly performs for himself. “Do You Wish To Rise? Begin by Descending” (2013) catches a male dancer, curled up elbows touching knees portraits of the famed defector Rudolf Nureyev show him in close-up. The first, “A Puny Body Weakens the Soul” (2013), shows a man whose exploits on and offstage are strangely blurred away as he leans casually against a wall, clad in a muscular leather jacket. Nureyev is at rest, burdened with age and silently cognizant of impending illness. A delicate, rococo crown moulding on the wall behind him is an enhancement of the softness with which Gutierrez applies the paint. It is not so much sexy as it is weary. In the second, “God Is Justice, He Cannot Sleep Forever” (2013), he wears a jeweled tiara in full stage makeup and traditional ballet costume. Here, Gutierrez elects to use a poignant, biographical route, as if to invite the viewer into his dressing room while no one is watching. An earlier painter of baller dancers, Edouard Degas, left an indelible mark on visual history in his interpretation of classical dance; exercised not by nobility or dancers already famous, but poor chorus girls and great talents about to reach their peak. From that point on, all sincerity in revealing the environs of the ballet dancer stemmed from a faithfulness to a populist history. Aramis Gutierrez has zero qualms about the sharpness, faithfulness, or lack of both at the core of his practice. The secret lives of pinks, purples, blues, and grays are unveiled; they possess erotic charge and trigger fantasies of beloved performances.