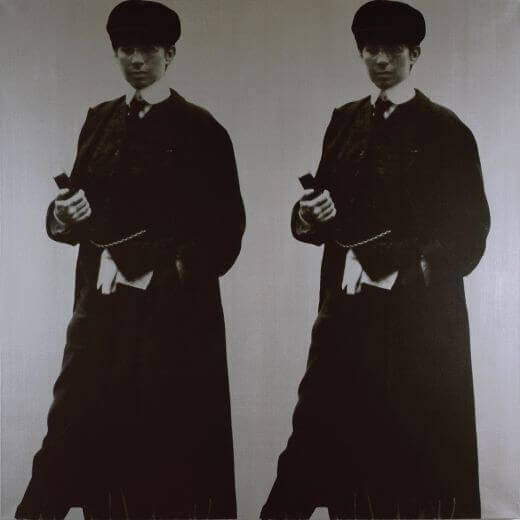

Deborah Kass, Double Yentl (My Elvis) Global Positioning Systems

Shana Beth Mason

Deborah Kass, Double Silver Yentl (My Elvis), 1993. Silkscreen and acrylic on canvas, 72" x 72" TK cm. Courtesy of the artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York

Through August 15,2015

Wander through the galleries on the ground floor of Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM), and you can’t miss the imposing, six-foot-tall double painting of Barbra Streisand dressed as a male rabbinical student. Streisand wrote, directed, and starred in the 1983 film Yentl. Based on Isaac Bashevis Singer’s 1950s short story “Yentl the Yeshiva Boy,” Streisand plays the role of a young woman in late nineteenth-century Poland who disguises herself as a man in order to continue her Talmudic studies. The screenprint Double Yentl (My Elvis) (1993) is part of an extended series by New York–based artist Deobrah Kass. Within the borders of the exhibition Global Positioning Systems (curated by René Morales), both the painting and Kass herself, as a vibrant creative personality, take on a compelling new shape.

“I hope you don’t mind if we listen to the radio,” Kass bellowed to me from across her Gowanus studio during a recent visit, “I have to listen to Jonathan Schwartz at noon, otherwise I turn into a pumpkin.” After admiring her distinctive gold necklace from which hung the word “YO” (which, flipped around, could also read as the Yiddish expression “OY”), we chatted about Pop culture idols and the dangers of creating and presenting creative work as a woman. But rather than rehashing tired concepts of Pop culture and representing the absence of meaning in capitalism, I ventured that Kass’s work, instead, points to the reinvigoration of Andy Warhol’s most successful ideas regarding image appropriation and identity politics while passing them on to a comparatively new audience in Miami.

For a person to locate her own identity (let alone her various identities among respective cultures and creeds) is a near-impossibility without some kind of anchor—something or someone that offers a gentler association than mere fly-by-night judgments. Miami’s own population and culture is highly volatile, largely transient, and still looking to assert itself against the more aged, entrenched collected ethos of places like New York and Los Angeles. Who is Miami? Who isn’t? These are questions that resonate in Kass’s painting. The character of Yentl is in a perpetual state of gender and identity crisis: she suppresses one form of desire (her love for a “proper” male student) in order to achieve what is politically and logistically beyond her control (her education). Realizing these opposing desires can never be reconciled if she remains in Poland, she emigrates to America. The recognition of Streisand as a public figure tends to precede any affinity or sympathetic identification with Yentl in Kass’s painting. For those interacting with the work for the first time in Miami, there may be different associations with the character than with viewers in New York (who can claim Streisand as one of their own, by birth) or Los Angeles (who can claim Streisand as a Hollywood legend and longtime resident).

The emphasis on Streisand as an actress/singer rather than the character she plays, is mirrored by what Kass experiences as an “artist” versus a “painter.” Kass seamlessly moves between and fuses both terms: a well-educated, Jewish, lesbian woman with a biting wit who refuses to be defined by terms altogether. She is dedicated to being a contributor (“painter” and “artist” are not mutually exclusive), a voice for women seeking validation in their achievements, not in their prescribed societal roles. The parallels between Streisand and Kass (“She owns one of the paintings and I’ve never met her. Isn’t that sick?” the artist scoffs), Kass and Yentl, Yentl and Miami, and Streisand and Miami are as complex as the web of relationships in the film (girl becomes boy, girl-as-boy loves man, man loves another girl, girl loves girl-as-boy). These nuances may be lost on a general audience at PAMM, but the painting’s placement among a series of images discussing how we, as a society, determine our own location among our close peers and distant neighbors serves a succinct purpose. That purpose is illuminating how we choose to move through the world to discover which place best suits us and our capabilities (given the chance to explore them). Deborah Kass is a singular sensation (she’s created paintings based on A Chorus Line, too), a formidable presence not only as a painter and teacher among her male and female art world colleagues, but in delivering a message in the guise of Streisand…dressed as a boy…but still a girl…well, you get the idea.