TWO AMERICAS AND THE OTHERS IN BETWEEN: A REVIEW OF TALES OF TWO AMERICAS

Chauncey Mabe

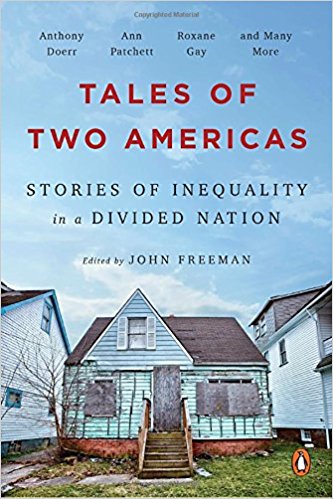

Line for line, page for page, piece for piece, the essays, stories and poems in editor John Freeman’s new anthology are uniformly excellent. A sequel of sorts to his 2015 anthology on inequality in New York City, Tales of Two Cities: The Best and Worst of Times in Today’s New York, the new collection features a mix of fiction, nonfiction and poetry. Some pieces are sharper than others. Joyce Carol Oates’ short story, “Leander,” considers the stain of white guilt, and addresses the question, is it indelible? Alas, Oates’s story—an elderly white woman attends a Black Lives Matter meeting at a black church, only to be driven away by her own discomfort—is tired and obvious. Oates wants to cross the divide, but like her protagonist, her effort is feeble, and irresolute. At least she makes the attempt. Too much literature by white writers exists in a colorless vacuum, as though race does not exist.

While Oates stumbles across the color barrier, Roxane Gay navigates it with ease. In the short story “How,” a young woman living in a Finnish community in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula works two jobs to support a drunken father, a deadbeat husband, a twin sister, the sister’s husband, and the sister’s baby. A Haitian-American writer best known for nonfiction, Gay effortlessly imagines the inner life of a working-class white woman. The story is a marvel of understated desperation. “Peter would prefer to have sex everyday. Hanna would prefer to never have sex with Peter again, not because she is frigid, but because she finds it difficult to become aroused by a perpetually unemployed man.”

The power of Gay’s story provides a clue to part of what’s missing from Tales of Two Americas. Most of the pieces focus on the white-nonwhite divide, the gulf between Americans who enjoy “white privilege,” whether they know it or not, and those who are keenly aware of their exclusion, among them African-Americans, Latinos, Asian-Americans, and immigrants. To be sure, this remains underexplored territory, and the voices of people of color are to be encouraged and heeded. But the 2016 presidential election left more than half the country in a state of utter shock, unable to comprehend how the other half chose Donald Trump as president. Contrary to the title of this book, there are more than “two Americas” in today’s fractured national landscape. Gay understands that America is divided not only by race or color, but also by class. Would

Hanna vote for Trump? Maybe, maybe not. But the men in her family almost certainly would.

That’s not to say Freeman neglects the discontents of the white working class, but apart from a piercing short story by RS Dereen, “Enough to Lose,” the pieces addressing the matter are shallow gestures of liberal condescension. Richard Russo, Larry Watson, and Timothy Egan contribute brief essays on the loss of working class dignity, and each is fine in its small-bore way. But they are the work of affluent liberal intellectuals, sitting in their studies, remembering how things used to be, postulating on how things got to be the way they are. Not one seems to have talked to a contemporary working class person.

It’s not as if we know nothing about Trump’s America. George Saunders, writing for The New Yorker, attended Trump rallies during the 2016 campaign, talking with Trump supporters and returning with reports that confound general wisdom about them (Hint: Many voted for Obama. Twice). Nancy Isenberg’s White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America, is just one of many recent books that explore the question of who all these white people are and why they are so angry. Arlie Russell Hocshild’s Strangers in their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right was a finalist for the National Book Award. Raised in Appalachia, I have many issues with the right-wing slant of Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis, but its author, J.D. Vance might have lent a valuable voice to the discussion. Could none of these writers, or others like them, be recruited for Tales of Two Americas?

The stories, poems, and nonfiction centered on the traditionally downtrodden—immigrants and people of color—are much stronger, even the ones by white writers. “Death by Gentrification: The Killing of Alex Nieto and the Savaging of San Francisco,” by Rebecca Solnit, is a powerhouse of investigative feature journalism. Beginning with the senseless police killing of a 28-year-old security guard, the piece pulls back to show how the influx of affluent tech workers has fragmented the city’s sense of community: “When, for example, someone who worked with gang kids got driven out, those kids were abandoned. How many threads could you pull before the social fabric disintegrated?”

Kiese Laymon contributes an anecdotal essay, “Outside,” that exposes the human cost of America’s mass incarceration system: “Dave, the first person I met in Poughkeepsie, was a felon because he was black, scared, desperate, and guilty. My student Cole, a heroin user and dealer of everything from weed to cocaine is a college student because he’s white, wealthy, scared, desperate, and guilty.” In the essay “White Debt,” Eula Biss challenges the entire concept of whiteness, while also examining its moral cost: “Collusion is written into our way of life, and nearly every interaction between white people is an invitation to collusion.” Edwidge Danticat’s short story, “Dosas,” evokes the complexities of immigrant life in its account of a Haitian nurse who is swindled by her ex-boyfriend and her ex-best friend. And in Danez Smith’s poem, “i’m sick of pretending to give a shit about what whypeepo think,” breathtaking beauty rises from a spirit pushed beyond anger: “i’m done with race,” the poem declares, then adds, “hahahaha could you imagine if it was that easy? to just say I’m done and all the scars turn into ravens…”

By exposing readers to these pieces, and others, like Nami Mun’s story about Korean immigrants recruited into the exploitation of other immigrants, or Ann Patchett’s meditation on Christian compassion through the life of a Catholic priest devoted to the homeless in Nashville, Freeman does readers a great service. “America is broken,” he writes in his introductory essay. “You don’t need a fistful of statistics to know this.” In this volume, Freeman the essayist sees more clearly than Freeman the editor. Tales of Two Americas may be a great title, but it ill serves its subject. America is fractured right now into many more than two pieces, and some important ones are either missing or misrepresented, making this collection less than the sum of its parts. Lest that sound harsh, let me add that the parts provide much value—insight, humanity, empathy, outrage, but most of all, profound reading pleasure.

Chauncey Mabe is a freelance writer based in Miami. For more than 20 years, he served as book reviewer for the Sun Sentinel newspaper in Fort Lauderdale. His work has appeared in the Miami Herald, the Toronto Globe & Mail, SUCCESS Magazine, the Palm Beach Arts Paper, and the Chicago Tribune.