The Nature of Desire: Dash Snow at the Brant Foundation

Ed Winstead

Dash Snow, Fuck the Police, 2005–07. 45 framed press clippings, semen. Courtesy The Brant Foundation, Greenwich, CT. Photo: Christopher Burke

Dash Snow, Fuck the Police, 2005–07. 45 framed press clippings, semen. Courtesy The Brant Foundation, Greenwich, CT. Photo: Christopher Burke

I thought recently of both these things while standing next to a polo field outside Greenwich, Connecticut. This was at the Brant Foundation Art Study Center, an elegant former stone barn backed up against a huge expanse of unblemished green. At first blush it might seem a strange place for Dash Snow: Freeze Means Run, an exhibition of the artist’s work, full as it is of come, blood, and downtown grime, and evoking, as it did, those two strange memories. But the more I thought about it the more it made sense. He overdosed at the Lafayette House, a boutique hotel on East Fourth Street where a room, maybe even the room, if you’re one of those sorts of people, goes for about $400 a night. Snow was famously of the de Menil family, who are both extremely rich and prolific collectors of art, and was equally famously estranged from them, having run away as a teenager in pursuit of those all-time great fuck-yous: drugs, booze, and graffiti. So I guess it’s not the craziest thing in the world, this parabolic exportation of Snow’s work up to Greenwich, as rich and boring a place as you’re likely to find.

The upper floor of the exhibition space is dedicated largely to sculpture and collage, the lower to an excerpt of Snow’s voluminous Polaroid output and three video installations. Everything was organized by Snow’s friends Dan Colen, Hanna Liden, and Nate Lowman, along with Peter Brant himself and Dash Snow Archive director Blair Hansen. The result is somewhere between myth-making and tribute; it is a love song to the late artist on the one hand and a market-minded spectacle on the other, which, as with the geography of it, isn’t so much a jarring mistake as a reflection of Snow’s career.

Against one wall upstairs is the 2006 assemblage Bin Laden Youth, which seems a good enough place to start. It’s a chair, the kind you might find in the home of a friend prone to dragging shit out of their grandparents’ attic, facing a stack of cinderblocks, painted black, on which are propped a rusty curved knife and a mirror covered with the eponymous phrase. Over the back of the chair is the same T-shirt I’d seen on the kid in the hospital, NEW YORK FUCKIN CITY, some studded leather straps, chain mail, and a shining medieval helmet. It’s not terribly ambiguous, this comparative barbarism, but it is interesting how central a place in Snow’s work the trauma of 9/11 occupies. He was twenty at the time, and the abandon that he and his compatriots embraced, that became their defining trait, is often couched explicitly as a reaction to it. Interesting because it manifested less as a turn outward, toward a world and a species that could conjure disaster on such a scale, than as a borderline-solipsistic retreat inward and away.

There’s a bald anti-authoritarian streak across the board, embodied most exuberantly by Fuck the Police (2005), a series of forty-five framed newspaper cut-outs, all stories on police corruption, abuse of power, and brutality, which Snow had jerked off onto. Much less surprising than their continued relevance is the idea that anybody thought they wouldn’t be. What stands out instead is the tendency they illustrate toward semen-as-weapon (which doesn’t take a whole lot of unpacking to seem pretty retrograde), an even more aggressive example of which appears downstairs, in the 2007 video installation Untitled (Penis Envy). The piece takes as its jumping-off point a line from Ariel Levy’s profile of Snow and company that ran that January in New York magazine: “How much talent does it really take to come on the New York Post, anyway?” Snow printed it out, poster-size, and came on it. Then he put another enormous copy in a light box, projecting up onto the ceiling of Peres Projects, and paid a series of men who’d responded to an ad to all jerk off on that, too. This seems a very good distillation of the show as a whole: funny, possessed of a certain kind of cleverness (if often second-hand—see Dada, mid-century counterculture, Warhol’s oxidations, the ‘80s in general, etc.), and very dynamic, but so dynamic as to be almost thoughtless. However much talent is required, plenty of people evidently have it. Wrecking hotel rooms and turning them into hamster nests, an exercise that culminated in the famous installation at Deitch Projects, is a great way to show off your disdain for the establishment if and only if you ignore the people making minimum wage who clean it all up. Fuck the man, sure. But when you’re paying the homeless $10 to let you tag them (pretty debasing), as Snow did, then fuck you, too.

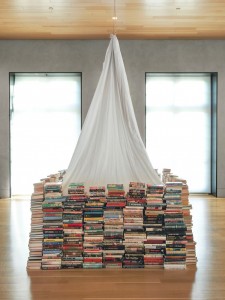

Dash Snow, Book Fort, 2006–07. 1,122 books and mixed media. Ettore and Lorenzo Nesi Collection. Photo: Christopher Burke

Dash Snow, Bin Laden Youth, 2006. Cinderblock, spray paint, mirror, chair, T-shirt, knife, helmet, harness, chainmail, and American pin. Collezione Il Giardino Del Lauri, Italy. Photo: Christopher Burke

Ed Winstead is a writer and editor based in New York.