Meredyth Sparks: So I Will Let It Alone And Talk About The House

Cara Despain

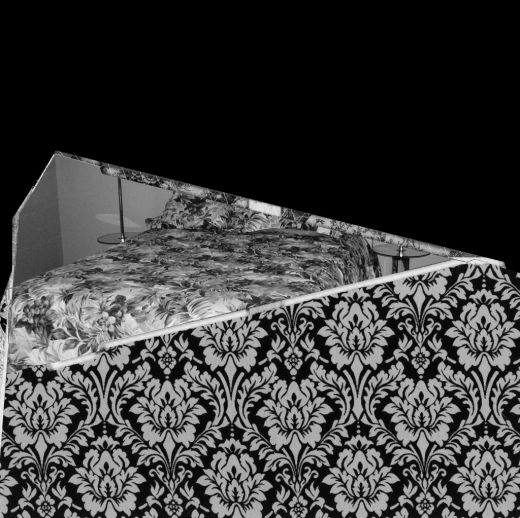

Meredyth Sparks, “Untitled,” 2012. Digital print. Courtesy of the artist and Locust Projects.

Vacant and unspecific, the mixture of fabric, texture and structure constructed a loose narrative uncommitted to any one location. The patterns, furniture and shrouded decorative quality of the works served as psychological indicators to her idea of extraction—which aims to pick out an intimate space at any moment and exploit the undertones. The wallpaper and linen designs enforced a mass-produced aesthetic, and the clean and subtle sensibility, especially in the collage pieces, made the slivers of photographic images of interior space poignantly effective. A perfectly made bed or a nondescript interior somehow triggers a nostalgia that is transient and transitive but cannot be placed as altogether familiar—similar to Diane Keaton’s photographic series Reservations, that depicts mostly empty hotel lobbies where she traveled.

Meredyth Sparks, “So I will leave it alone and talk about the house,” 2012. Installation View. Photo courtesy of the artist and Locust Projects. Photo: Chi Lam.

A symbol of privacy within a private space, the multi-paneled dressing screen in the center featured obscure images of Bette Midler’s early performances layered onto a lattice structure itself wrapped in a photo of a wooden screen. The intentional confusion of physical objects and their two-dimensional representations made it an apt sculptural complement to the collage work in the show, but the abstracted images of Midler seemed to conflate two separate interests. The implications of this depiction of the singer’s stage persona perhaps better fits Sparks’s overall oeuvre, but here it felt tangential. The imposition of gender and reference in both these pieces didn’t hurt the work, but felt slightly unresolved or unreconciled due to being tied to specific figures. It dissolved the ambiguous psychological environments the others

achieved.

Because these works were larger and functioned like centerpieces, their relationship to the concept begged consideration—but the strength and tone of the two-dimensional works was notable. It is the sophistication of these that shouldered the weight of the show; they guided viewers to extract associations for themselves, rather than providing them one option to decipher.