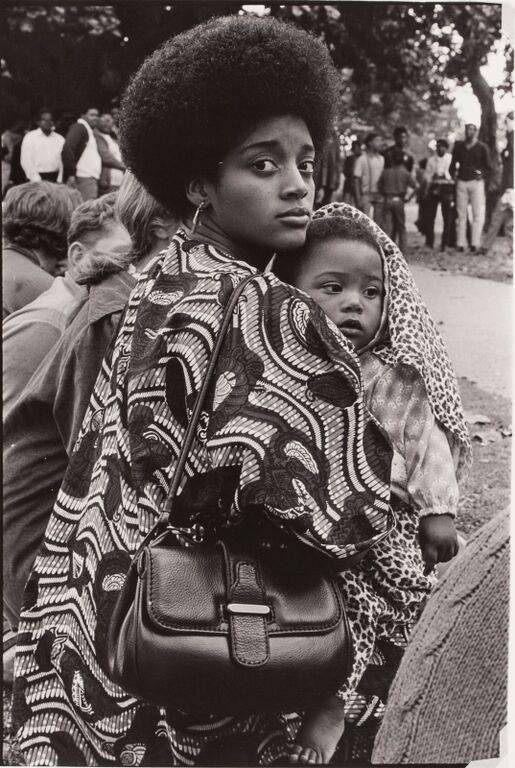

Ruth-Marion Baruch, Mother and child, De Fremery Park, Oakland, CA, 1968. Gelatin silver print (selenium toned). Norton Museum of Art, Gift of the Pirkle Jones Foundation, 2013.73

July 30–November 29, 2015

Earlier this year, the death of a black man resulting from police-inflicted injuries provoked uprisings in Baltimore. The mass media gave us few images of black people protesting peacefully, focusing our attention, instead, on rioting, looting, and the possibility of gang violence. More than forty-five years ago, husband-and-wife art photographers Ruth-Marion Baruch and Pirkle Jones resisted similar demonizations of black protest. Their sympathetic portrayals of Black Panther Party members clashed with damaging images that filled the news. Twenty-two black-and-white photographs from their original photographic essay comprise The Summer of ’68: Photographing the Black Panthers.

In 1966, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale founded the revolutionary socialist Black Panther Party for Self-Defense to challenge police brutality against the black community. Panther patrols carried loaded guns and asserted their right to revolution, distinguishing the group from pacifist Black Power movements and earning them a reputation for organized thuggery—a reputation propagated by the media and the FBI. The popular press failed to mention the Panthers’ demand for education and decent housing or their community-based initiatives such as Free Breakfast for Children.

Baruch, a member of the left-wing Peace and Freedom Party, shared the Panthers’ commitment to social justice and sought to correct their distorted image. A German-born Jew, she had expe- rienced prejudice first-hand, while her husband never forgot his father’s horrific descriptions of lynchings in the South. The couple’s social consciousness coincided with heightened political awareness throughout America in the late 1960s.The two had met at the California School of Fine Arts (today the San Francisco Art Institute) as the first students in the first fine art photography program in the United States, founded by Ansel Adams in 1945. Their community of California art photographers included Adams, Edward Weston, Dorothea Lange, and Minor White. However, the classicist Adams did not support the couple’s socially conscious work. The long-time teacher and friend tried to dissuade them from working on the Black Panther project.

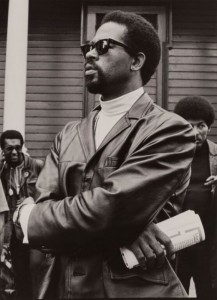

Pirkle Jones, Black Panther demonstration, Alameda Co. Court House, Oakland, CA, during Huey Newton’s trial, 1968. Gelatin silver print (selenium toned). Norton Museum of Art, Gift of the Pirkle Jones Foundation, 2013.41

Panther communications secretary Kathleen Cleaver also recognized the potent visual imagery in Baruch and Jones’s work. Their photographs appear in numerous issues of the Black Panther newspaper, which are displayed in the exhibition. Many photographs portray Panther leaders close up, including cofounder Newton, who the couple photographed in jail the day before his sentencing and whose gentle features belie his reputation as a violent criminal. Other photographs depict young couples and families, such as Baruch’s Mother and Child, De Fremery Park, Oakland, CA (1968), signifying the Panthers’ dedication to the community and its future. In fact, what is striking about all the images is the obvious youth of the Panther members and their supporters, a reminder that their struggles were rooted in a generational awakening that was taking place across America.

Ruth-Marion Baruch, Eldridge Cleaver, Minister of Information for the Black Panther Party, Editor of The Black Panther, Author of Soul on Ice, at Free Huey Rally, Bobby Hutton Memorial Park, Oakland, CA, 1968. Gelatin silver print (selenium toned). Norton Museum of Art, Gift of the Pirkle Jones Foundation, 2013.81

The Summer of ’68 shows us the importance of untold counternarratives. Today, the ease of snapping a photograph and disseminating it instantly makes these alternative narratives more accessible. The more of them we see, the less they’ll be considered alternative.