- “I’M HARRY SMITH AND I HATE YOU!”

- NO MORE SAND: Thoughts Composed Discursively aboard the SuperFast Gambling Boat Somewhere between Miami and Bimini

MOVING IMAGE: Screendance in Miami

CATHERINE ANNIE HOLLINGSWORTH

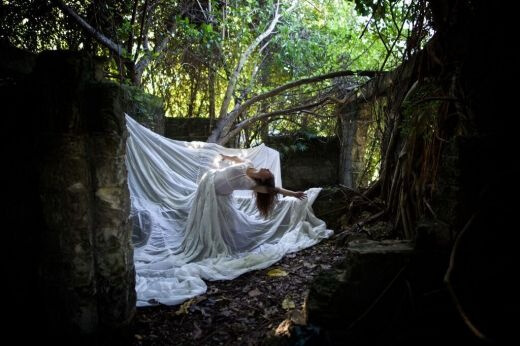

Production still from Ella, a film conceived and choreographed by Heather Maloney, directed by Carla Forte and Alexey Taran, produced by Inkub8 and Bistoury with original music by Omar Roque

And dance has some fixed variables. It is considered primarily a visceral form. Whether performers are professional dancers or untrained, the body is the primary focus and movements are determined largely by the performer’s capacity for movement. Physicality also places economic demands on producers. Between rehearsal and theater space, marketing, permits, and the cost of paying performers, the undertaking of a live performance can be costly.

In response to both the practical challenges of dance and the availability of new technologies, a novel genre has gained momentum over the last three or four decades. Depending on the time period, region, or exact definition of the form, it is variously called dance on camera, video dance, cinedance, kinodance, or screendance. In general, this is film or video featuring dance (or, more generally, movement) as opposed to dialogue or music. The dancers and audience are no longer in the physical space of the theater. Movement can be edited and composed so that the choreographers and filmmakers control exactly what is seen, and from which angle. Viewers might see performers’ eyes, skin, and emotions up close, with performers now unbound by real time or space. Actually, movement may not even be body-based. Some projects use animation or choreography set on objects.

The marriage of film and dance is as old as the moving image itself and has been a subject of continual investigation, especially at its more experimental edges. The Lumière brothers and Edison Studios made films in the 1890s of the serpentine dance, aspectacle of movement and light created through manipulationof a dancer’s costume. Fifty years later, most of filmmaker Maya Deren’s work had movement as a primary element; both A St udy for Choreography for Camera (1945) and The Very Eye of Night (1958) are explicitly dance/film mash-ups. Later decades saw film works by choreographer Yvonne Rainer, including Hand Movie (1966), as well as Trio A (staged for film in 1978). Rainer and others, including choreographer Merce Cunningham, collaborated with TV producers in the ’70s to stage performances explicitly for broadcast. And more recently, Lloyd Newson’s DV8 Physical Theater reset live performance pieces as long compositions designed for the camera’s eye. His The Cost of Living (for stage2003 and film 2004) and Enter Achilles(1995) are both considered exemplary dance on camera works.

In the last few decades, video cameras and editing tools have become ever more accessible, leading to an explosion in the production and distribution of dance on camera. This is true around the world, and in the microcosm of Miami’s dance community, where video components often appear in live performances or, vice-versa, performances might be produced exclusively for the camera. In 2009, local choreographer Rosie Herrera presented an untitled video piece produced with photographer and filmmaker Adam Reign as part of Various Stages of Drow ning: A Cabaret. This piece stands as one of the earliest and most visible local danceon camera productions. Since then, almost all of Miami’s notable choreographers, including some who have since left town, have produced at least one dance on camera work. For a creative community that embraces collaboration not only between dancers and choreographers, but also crossing into visual art and film practitioners, the genre is a natural fit.

Dance on camera has become something of a bandwagon, with its low entry investment of time, skill, and money. But this is also its virtue, making it a fertile ground for new work that invites play and experimentation. Multiple Miami choreographers have described the ease of producing dance on camerain contrast to the blood, sweat, and tears of a live show. When pieces are set in outdoor locations, as is often the case, they are typically done “guerilla-style,” with just the dancers and the filmmakers, and without permits. They may even be improvisational, with participants composing on the fly and editing later. Works can be set in locations that would be difficult or impossible to use for live performances: by the ocean (as is commonin Miami productions), out in the street, in overgrown natural spaces, or abandoned buildings.

Noting the increase in moving image work coming out of the local dance community, Tigertail Production’s Mary Luft came up with the idea for a festival devoted explicitly to the hybrid form, and ScreenDance Miami was born. Marissa Alma Nick, a local choreographer, was chosen to direct the festival. In 2013, Tigertail posted an open call for the first annual ScreenDance Miami, and the festival’s third annual program will be screened in January.

ScreenDance Miami was conceived with multiple intentions. First, it recognizes and provides a venue for the type of work already being made in Miami. Second, it gives local producers an opportunity to have their work seen by an expanded audience. Screenings will be held at Pérez Art Museum Miami, Miami Beach Cinematheque, and Mana Wynwood, opening up the program to visual art, film, and more general audiences. And third, it creates an opportunity for dialogue with other creators around the country and internationally as a means of stimulating intellectual and artistic growth locally. To this end, the festival accepts submissions from Miami-based artists and those producing elsewhere. Tigertail has also partnered with Cinedans, a more established festival in Amsterdam, and ScreenDance Miami 2016 will include some Cinedans programming for the second year in a row.

Luft is specific about the term “screendance.” As she explains it, the larger category of “dance on camera” might include work that is more documentary, or more about dance and less about the camera. Luft describes screendance as a subset of dance on camera, work that can only exist in its on-screen form. Sincethe genre straddles traditional categories, ScreenDance Miamiis open to choreographers as well as performance artists, visual artists, filmmakers, animators, and anyone else producing movement-based film or video.

Luft observed that the accessibility of digital tools has rapidly changed the type of work being created, and that younger artists are naturally inclined to adopt new technology and run with it: You can get a GoPro and put it on your wrist and choreograph or dance with it, or put it on your head. Or put it on your boat, your bicycle, et cetera. It’s an inexpensive small camera, and you can edit really easily. Young people are moving into new technology incredibly fast. They’re picking it up and using it, and playing with it. In the past something like that was not available. It was very expensive, it was too difficult and too time-consuming.

Yet a tension remains between the pace of invention produced by technological change and the long-term investment required to master either film or dance. On the subject of screendance, Miami-based choreographer Pioneer Winter, along with choreographer Alexey Taran and his creative partner and filmmaker Carla Forte, foreground the importance of high-level collaboration. They each describe the better examples of screen-dance as those with sophisticated camera work that hasbeenintegrated with the dance component. Usually this equates to the invested input of a cinematographer, not just a dancer who picked up a camera. Winter argues that experience is indispensable. “I could give a $3000 camera to an amateur and what they come up with might be a hell of a lot worse than a real filmmaker who’s just doing something with their phone. I think it’s one part technology and two parts skill.”

Forte agrees. “I think that right now, a lot of people think that they can make films. Or dance on camera films. I’m not disappointed by that, because you can do whatever you want. But you have to be more informed about it.” Her recent screendance project with Taran and Miami choreographer Heather Maloney, Ella (2015), was made over the course of Maloney’s pregnancy, and we see Maloney’s physical and emotional transformation up close in the space of about fifteen minutes. Ella displays a collaboration between multiple individuals each accomplished in his or her own arena.

The potentials and pitfalls of screendance illustrate larger dynamics in multidisciplinary work generally. Some would argue that it no longer makes sense to consider oneself a sculptor, ora dancer, or even more generally a visual artist, claiming these medium-and genre-based definitions as obsolete. Taran describes why his company, Bistoury Physical Theater, uses both live performance and film:

If you walk in the street and you close your eyes oryou open your eyes and you aren’t thinking about your problems, and you start to focus on what’s happening around you, you can have here in this side of the wall, a shop with a lot of televisions. And they have Telemundo here, or they have MTV here, they have something here. You have the homeless on the street sitting, you have a woman dancing there. You have some music that is coming from here. You have a bus passing you.

Film and dance in combination, then, are a more complete reflection of daily life, where multimedia information is inseparable from our physical lived experience.

Certainly, opportunities grow from the dissolution of stagnant ideas and hardened boundaries. With the possibilities for danceon camera seemingly infinite and largely unexplored, the genre holds promise as a relevant contemporary form. This is particularly true in Miami, where cultures, languages, and multiple art histories and practices are in constant negotiation; artists and residents live sometimes here and elsewhere; and the output of the creative community depends on interchange beyond our local geography. A danger on the flip side is a loss of quality. Whena lifetime of dedication to one medium, whether film, painting, dance, music, or even graphic design is replaced with dabbling by beginners who have easy access to tools but no training or sophistication, the field gets diluted.

Catherine Annie Hollingsworth is a Miami-based dance and performance writer.