- Austerlitz in South Texas

- A New Day Has Come: A Review of Radical Hope: Letters of Love and Dissent in Dangerous Times

This World We Think We Know so Well

Lucas Zwirner

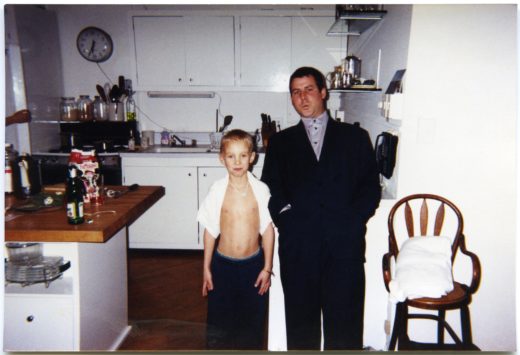

Lucas Zwirner and Jason Rhoades, c. 2000

Lucas Zwirner and Jason Rhoades, c. 2000

After the show came down, Jason let me use the little bike all summer. I discovered a hidden path off Otis Lane near my family’s house in Bellport, and I rallied around there for months, creating obstacle courses, crashing, and driving again. Then, one day in late August, while I was riding in circles on the lawn, a friend of mine aimed Jason’s air rifle at me and fired. I swerved, fell down and became hysterical, screaming incoherently the way children often do when they aren’t sure how much pain they’re really in. I had a bruise the size of a cherry on my back for weeks.

I never got to tell Jason this story—he died the following summer—but he would have loved it. And in a way, for me, it holds clues to one of the most significant aspects of his work.

Jason loved the seemingly insignificant—chance connections and encounters that present themselves over the course of everyday life. He hunted for them, was always alert to them, and when he found one, he would pour his energy and thought into it until the moment became a system of connections, the system a work of art.

The early piece Swedish Erotica and Fiero Parts (2004), recently on view at Hauser & Wirth in Los Angeles, is a case in point. The large, room-sized installation is filled with a mass of different light-yellow objects—some naturally yellow, some painted—all playing on the Swedish company Ikea’s yellow logo. The yellow is the artist’s version of brand identity: something that arbitrarily confers unity on a diverse group of things. But the entire project relies on a bizarre coincidence—that Jason arrived at his then gallery (Rosamund Felsen) and found it painted yellow. He was subsequently told that famous images of Marilyn Monroe had been shown there, which in turn reminded him of photographs of his mother with bright blonde hair posing as Marilyn Monroe. The network of thoughts led him to ideas about America’s libido-driven consumer culture, all of which tied back to Ikea and the yellow gallery as a marketplace.

On the one hand, there’s the chain of associations; on the other, there’s the moment—strange and potent—that sparks the chain: some resemblance among things, some intuitive leap between objects, unseen by others, often humorous, usually dark and a little perverse. Jason loved these private links because they helped create the inner order of his work.

In The Costner Complex (Perfect Process) (2001), a project at Portikus in Frankfurt, Jason developed the idea of radiating canned vegetables with the oeuvre of Kevin Costner while flying back and forth between America and Europe, watching Kevin Costner movies, himself canned on the plane. In Rhoades Construction (1993), one of Jason’s final pieces at the University of California Los Angeles, his last name provided the pun that became an installation with a pneumatic drill he used to carve students’ names into the hallways of the UCLA art school (for a small fee). In My Brother/Brancusi (1995), it was Jason’s sudden vision of a resemblance between Brancusi’s studio and the compulsive ordering of his brother’s room—a pairing that begs the question: if both men order things obsessively, why is only one of them a great artist? (While I was in the piece, I overheard one visitor ask: “Do you think all extreme hoarders think they’re artists but never make anything like this?”)

Another important part of Jason’s gift for association grew out of his dyslexia and dysgraphia. If you look at the drawings in My Brother/Brancusi you’ll see numerous instances of creative spelling: “The Donut machene must be un pluged” or “the Red of the Red parts must glisson” or, in the piece he gave my father for his fortieth birthday, the quite powerful “Fuck Fortey.” Jason had no qualms about any of this, and the looseness with which he approached language, already unstable, afforded him the ability to make new meaning quickly, when one word sounded like another or was spelled like something else.

In moments of instability, where most people would see only noise, Jason saw for an instant the understructure of things—a set of relationships otherwise obscured by rules and regulations, language and decency. This he tried to systematize, make present again in the intensely specific, yet often chaotic-seeming order of his own work.

Black Pussy (2005–2006), Jason’s cabaret-cum-nightclub, is perhaps the greatest example of the search for what unpredictability reveals. The original Los Angeles iteration was a kind of nightclub where Jason hosted a total of thirteen soirees. The nights were structured around specific activities: the Johnny Cash room where you could buy art for cash, a macramé station, a “pussy harvest” in which audience members were asked to shout out new words for vagina that were then added to a long list (in the end, Jason had over 6,000). The activities were attempts to shake people out of their comfort zones: no safety nets, as Jason often said. And the unpredictability of the soirees became the machine that made the work. The space itself was designed to facilitate the unexpected—the strange collections of objects, the lighting, the darkness, the cables, the celebrity impersonators, the small stage, the lounge area. People were invited to mingle in a space they didn’t know how to navigate, and Jason was there to capture all the unforeseeable moments when, late at night, the energy of the underside of things became palpable.

There is some magic in shared birthdays, unexpected meetings, moments in which unrelated people and disparate objects come together to make a world. In the case of artists like Jason, perhaps these moments are exciting because they mirror the mysteries of creativity itself—the ability to spin worlds out of unplanned puns or stray drops of paint (if we think of Turner). It’s as if these moments allow an artist to say: “Only my mind, right now, could have felt and created the connections you sense here.” Or: “Everything worthwhile happens far away from what we think we know.”

My own story about the gun and the dirt bike and the shooting might have carried some of that same coincidental magic for Jason. The young son of his gallerist, the ramp that the same gallerist hadn’t sold, the house in Bellport where both bike and gun were used, and that fateful late-summer day when the pellet struck my back. He might have seen some cosmic order, not a predictable sequence of events, but something felt in the fabric of life and use that confers meaning upon objects, whether we acknowledge it or not.

Jason had a deep affinity for all that objects mask: their labor, their previous appearances, their parts, and the myriad manipulations that go into their construction. He found worlds beneath the surfaces of things and thoughts and people; his installations are these surfaces turned inside out, refracted through his particular prism.

Lucas Zwirner is editorial director at David Zwirner Books, where he recently began the ekphrasis series, dedicated to publishing short texts on visual culture by artists and writers, rarely available in English. He has also written on numerous contemporary artists and translated books from German and French.