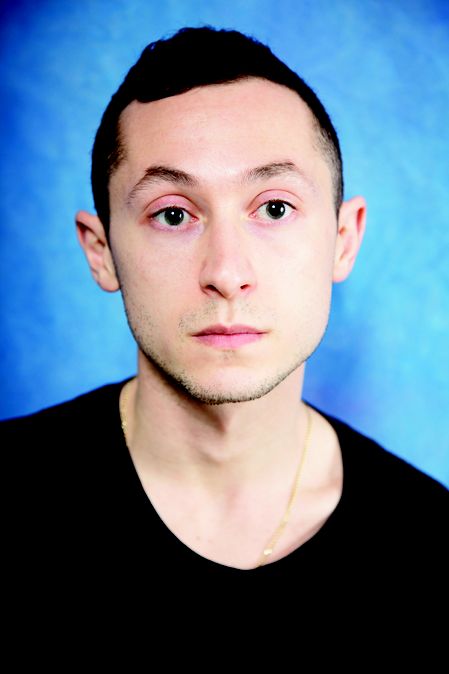

Alex Gartenfeld: In Conversation With Heather Flow

Heather Flow

HEATHER FLOW (RAIL): Let’s start by speaking about the role of the writer and the role of the curator. Do you differentiate between these roles?

ALEX GARTENFELD: Yes and no.The question involves the performance of a public role—acting within the framework of a community as a critic, rather than the performance of the role of a curator. Certainly, they demand a different field of relations. And while the critic can shape the way that information is received, the curator has perhaps the most active role in new relations. But both are public roles that today involve mediation but are also deeply rooted in public service. And beyond this, the field of contemporary art demands consideration of the relations between people, between objects and between people and objects.

This kind of ontological inquiry is important. I am interested in contemporary art because you are forced to ask yourself these kind of fundamental questions about power and about structures every time you enter an exhibition. Encountering this depth of inquiry is how you decide—as a curator or as a critic—that something is effective or productive or progressive.

I am excited to enter into an institution because these questions happen within the public domain. An article can be imminent too but the idea of a zone in which images circulate and people discuss and exchange with one another is a high priority for me.

RAIL: In regards to the circulation of images, and the discussions and exchanges prompted by those images, let’s speak about the two projects spaces you have co-founded since 2009. Both were situated in apartments.

GARTENFELD: The first was called Three’s Company, which I initiated with Piper Marshall, the assistant curator at the Swiss Institute in New York. I was working for Brant Publications, as the online editor at Interview and Art in America, and at the time both Piper and I felt that there was a necessary space to fill in terms of promoting critical artistic practice in an intimate context. We did shows with Tobias Kaspar, Asher Penn, Lisa Tan and Leigh Ledare. We hosted in the tiny space a performance by Rich Aldrich and his band. The shows were early in these artists’ developments. Our final show featured the work of Dan Graham, Nicolas Guagnini and John Miller, grounded in a historic proposition by Graham. Because the space was so tight, the domesticity of the space was quite felt, and an element in the presentations.

When the project reached its natural conclusion, I thought about how best to address my developing interests. I was commissioned to create a number of exhibitions in other spaces, and collaborating with many more artists. In the summer of 2011, Matt Moravec and I initiated West Street Gallery, where the focus was on two- and three-person collaborative exhibitions by emerging artists.

RAIL: While you have collaborated extensively, your curatorial experience leading up to your new position (Curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami) has been as an independent curator. What made you feel comfortable moving to a full-time position at an institution?

GARTENFELD: Well, I was always working with the magazines, which are obviously commercial enterprises but which have extensive institutional histories and connections. And for the upcoming exhibition Empire State at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome, I have been working within a museum’s structure for the last three years. And when we were working on an exhibition for New Jersey MoCA (which is a museum that never really manifested) that was, in a limited way, an institutional premise. In some way the lines between institutional spaces and commercial spaces are fluid, or function, and in others the line must be defended.

I am excited to join an institution full-time because of the museum’s history of innovative programming. That it is a collecting institution is interesting in terms of creating a record of works that interface in service of but also on behalf of a general public. The collection follows from exhibition programming and corresponds to a model of local exchange and education. The idea that you enter a museum that belongs to you and the community changes the identity of the work there during the period of the exhibition. Additionally, much of my work over the last three years has involved the intersection of art and geography or urban studies. I am excited to apply some of the models I have used to address New York to Miami, a city with unique economic, political and social histories.

RAIL: Could you let me know a little more about this work on geography, especially as it pertains to Empire State, a study of contemporary New York art you co-curated with Sir Norman Rosenthal?

GARTENFELD: Norman and I were commissioned to make a survey of New York art for the Palazzo delle Esposizioni. We made an exhibition that responds to the layered assumptions that underlay the commission. We felt responsible to address the problematic idea of presenting or exporting a culture in a building that was constructed as an exposition hall, in the trajectory of affirmative nationalist exhibitions since the 19th century. Artists in New York are highly conscientious of the ways in which their community is networked or functionalized. This interest in unpacking the survey exhibition led us to consider the rehabilitation of the urban format in the last decade as a kind of late-modern reprisal. Empire State entails writing a history of New York over the last 10 years, and the relevant developments in gentrification

and, related, the instrumentalization of art.

RAIL: Let’s talk about the exhibitions that inspire you. What exhibitions have excited you over the past few years? Or, what exhibitions do you anxiously anticipate in the coming years?

GARTENFELD: It seems over the last few years in major exhibitions, curators have been looking for new and renewed access to what was called “expanded visual culture.” Some are looking at animism, others at mid-century curators like Pontus Hulten who were thinking about the ready-made and expansive visual culture. But it’s important to remember that by the late 1980s work considered in this field was proposing major structural changes in the reception of culture.

RAIL: I’m reminded of the 1969 show Art by Telephone, organized by Jan van der Marck at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. The exhibition prompt asked a set of artists to make sound works remotely via phone call. Playing with the telephone and the means of connectivity makes for a rather experimental model of exhibition making.

GARTENFELD: An exhibition like this foregrounds the role of the curator in contextualizing form, but also in generating it, which is certainly a problematic that remains. In some ways it’s impossible for an exhibition like this to feel progressive today. Not merely because the telephone seems somehow dated, but because the curator cannot just task the artist with a premise. The artist must have the opportunity to re-situate herself vis-a-vis the technology.

To specify using a “hot topic,” for a field like net art to be effective, it has to be able to circulate in a way that transcends the technological support—that goes beyond mere description. If work is circulating on a site like Tumblr, you have to complicate the data field. Institution critique, and specifically the form of the leak, arguably originated within the field of contemporary art, with Hans Haacke. Contemporary art cannot sit comfortably on these artificial supports.

This field will inevitably develop rapidly over the next few years. Yet it is easy to incorporate quote/unquote net artists within programming and education programs, and more difficult to think about how you they might reinvent an exhibition platform. That is definitely one priority in my exhibition practice.