- Betty Tompkins: Sex World/WOMEN Words, Phrases, and Stories

- MIRROR STAGES: Brookhart Jonquil in Conversation

New Ideas for the Administration

Laura Randall

Copyright 2017, Paul Morris Morphoto.com

For many years, Lombard has played a prominent role in shaping Miami. She has called for an evaluation of how we view our urban centers, looking at the impact our environment has on our wellbeing—how people living near parks have lower heath risks and how social connectedness promotes happiness. Lombard advocates open-space master plans and affordable housing options. She also argues that we should look at landscape, like mangroves, as active agents in dealing with climate change. Concrete and asphalt cannot be solutions to sea level rise in perpetuity.

As Lombard presented her ideas about Miami’s need for welcoming public space, I began to think of German philosopher Walter Benjamin’s visit to Moscow, ten years after the Bolshevik Revolution. Benjamin wrote of his first experience on a tram there as “a tenacious shoving and barging during the boarding of a vehicle usually overloaded to the point of bursting [that] takes places without sound and great cordiality. (I have never heard an angry word on these occasions).” The philosopher dissected cities like Moscow, Naples, Marseille and most famously, Paris, through his experiences on foot. He ruminated on the impact a city’s plan and architecture has on the way people live, how they think and what shapes their aesthetic sensibilities.

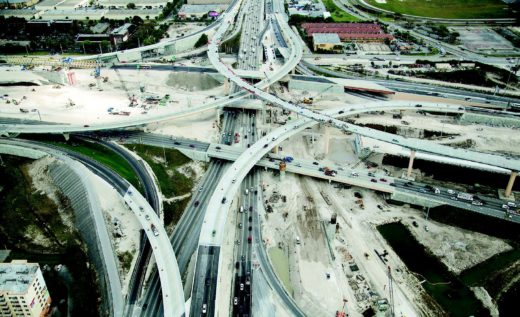

Miami is not a city that can be experienced on foot. To experience Miami-Dade as a resident, far removed from the posh art deco hotels on Collins Avenue, is to feel the transponder affixed to your windshield sucked dry by every ensuing toll booth. Despite the favorable weather, we are a city of drivers. The division of space in Miami-Dade began in the early days of single state roads when much of the land was still wet and uninhabitable. This graphic conquest of the environment is visible along SR836, which cuts through waterways with perfectly straight lines, forming a pattern of grids that collect in reservoirs as drivers encircle them to head northbound and southbound to the Ronald Reagan Turnpike. Ibis walk along the medians and flank nearly every road in the county, struggling alongside indigenous and invasive flora and fauna for access to green space. Cars flood Miami-Dade’s downtown areas at dawn, and retreat at dusk in a mass exodus to suburbia. The cordiality of Benjamin’s Moscow metro is nowhere to be found.

Lombard has made it clear that there exists a fight to develop Miami-Dade County with a flâneur’s mentality, cultivating accessibility, charming public spaces and street culture. But who is engaging in the fight? In the most recent elections, no new officials were elected to Miami-Dade County commission seats. The chair of transportation won uncontested, as did two other commissioners. Opa-locka reelected their commissioner. Doral elected their former mayor instead of the incumbent, and the City of Miami had no elections for seats in the commission in Fall 2016. Only the City of Miami Lakes elected a new mayor.

So when new ideas are being presented to the “New Administration,” to whom are we really speaking?

Laura Randall is an independent curator and a part of a collective of artists/scholars for the project space IRL Institute in Little Haiti. Laura works as the Archivist and Registrar for the Rubell Family Collection. She holds an MA in Art History from the University of Florida.