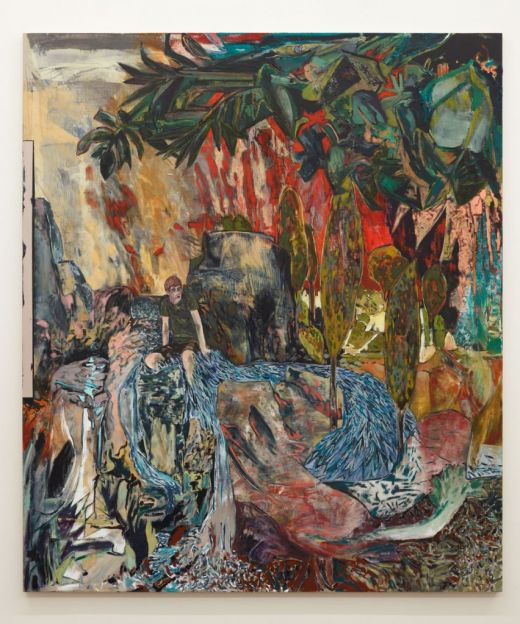

Hernan Bas, Against the Stream, 2013. Oil on canvas, 7’ x 6’. Photo courtesy of Fredric Snitzer Gallery.

APRIL 12-MAY 27, 2013

FREDRIC SNITZER GALLERY

Hernan Bas has characters—boys. How he places these young men in their landscape is his conceptual project. A method of reusing and repurposing historical systems is devised to create a blueprint for the work, with identity politics, medium specificity, studio labor poetics, and market dependency all functioning as proof of its own language.

In “A Boy in Peril” (2012), a series of tiny red and yellow paint blotches symbolizes a deadly coral snake. A boy stands behind, in peril, against dark rocks and cacti with an elegant sky simply represented by stripes of black, coral, and cadet blue. The five current oils on canvas in the exhibition are formulated by camouflaging boys against a wooded background—rapid brushstrokes along with murky sparkly color, strong long outlines, and concrete deposits of the palette knife craft an impasto environment.

The landscape, a play between fantasy and matter—illusion vs. material— spark notions of Greenbergian medium specificity (which basically means in its conventional category to be specific to the raw character of the actual material and surface: paint and canvas) while simultaneously producing a representational impression. The role of paint here is to stay material, but at the same time be allowed to describe. Under the “post-medium-condition” in which we are now obliged to look at Bas’s work, this tandem of medium and its form run alongside each other as parallels, liberating each from the other. This results in an open slate for the use of any subject and/or narrative. Here, that means lost, dandyish lads, playing with a flashlight, reading, sitting with their feet in a stream and simply waiting for something to happen. But nothing ever happens. The fact that there is a deep melancholy expressed in the subject almost presages how the work was assembled.

All functions of the work act as interchangeable variables. This open rubric generates a position for the use of ingredients like iridescent paints, and also tolerates fantastic painting tricks like using overtly textured white paint to represent water gushing from a fountain. More importantly, it allows for the romantic idea of the artist in his studio to be transposable with basic labor. Mirroring formal work with the idealized conception of art in the studio reflects romanticism as a contemporary instrument for value. Furthermore, it privileges all aspects of his language as forms of commodification.

In this way, Bas’s work is reduced to open systems of mix-matched value components that get their worth from outside structures. Concept next to medium (unlike concept through medium or concept over medium) in effect will always require exterior forces to provide its verification. Thus, the work will forever remain imprisoned by its sociopolitical identity.