How Raw Data Double-Crossed Miami’s Artists

Ahmed Mori

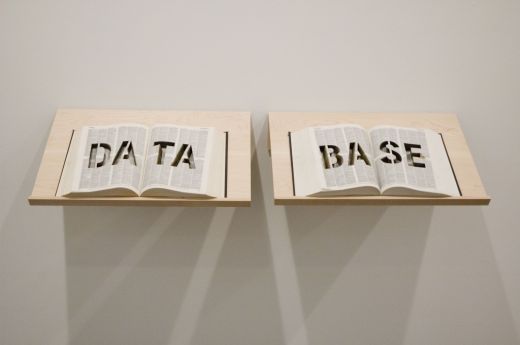

Michael Mandiberg, Data Base, 2011. Lasercut Oxford English Dictionary.

While much of the dialogue surrounding Miami—namely the existence of life after South Beach, beyond the ketotic geriatric clinics of old Florida lore—isn’t particularly bothersome, depictions of the city as a field for foreign locusts to descend upon every December make locals want to air their grievances in the form of open letters posted on Facebook. While Art Basel is a much-welcomed event that awards the local economy a $500 million yearly head start, it has done little to assuage concerns, both within the city and from afield, that the arts are not sustainable.

This poses a pressing question: Would Miami’s art scene thrive in a post-Basel world, once columnists are through captioning snapshots of Shepard Fairey and P. Diddy in the heat of a hip-hop half-hug? Indeed, Miami’s art cred was put into question with the release of the National Endowment for the Arts’s (NEA) new online data research tool in June. The organization made public a group of datasets culled from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) Tables listing the percentages of working artists across American cities, states and metropolitan statistical areas with populations upwards of 50,000. It wasn’t long before The Miami Herald decried the findings, shocked that Ames, Iowa could log a higher number of working artists per capita (1.6%) than the South Florida metropolitan area (1.5%), which came in 52nd place out of 368 regions.

The search for loose screws in the NEA’s methodology was not lost on Michael Spring, Director of the Miami-Dade County Department of Cultural Affairs. “We don’t often pay attention to these data studies because we don’t find them to be an accurate representation of reality,” said Spring. “They’re not usually good, equitable definitions of Miami’s art scenes. We’re also an immigrant community, which has been an issue with the census since I’ve lived here.” Indeed, Spring’s insights pose several questions about the NEA’s approach beyond that of data-dodging immigrants: the scope of the 11 artistic occupations tallied, artists’ distinctions between occupations and careers when self-identifying professions on census surveys, the long-running debate regarding differences between professional and amateur artists, and the occasional entrepreneurial artist who would rather side with her business over her creative output. “These studies tend to be a waste of time in regards to actually getting work done to help the art community,” he concluded.

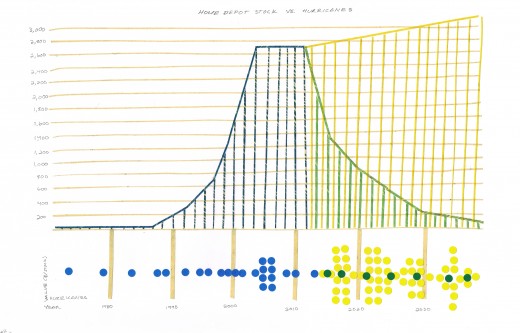

Olivia Ramos, “Home Depot Stocks vs. Major Hurricanes,” Tape on paper, 17 x 11″.

Beyond the methodology, however, there’s still something innately bothersome about these numbers, given the fever-pitched talk of a cultural renaissance among journalists and arts players. At the very minimum, one would expect faster growth for Miami’s working artist population after Art Basel, if not downright hockey-stick growth. Yet merely looking back at corresponding NEA numbers at the turn of the century doesn’t do much for a before-and-after diptych. While the South Florida Metropolitan area saw a 17.4% increase in civilian labor force, its working artist population rose at a slower 13.5% to 42,565 in a decade dominated by festival talk. Yet dozens of galleries have opened since the first Basel, a large cluster of which dot the fast-gentrifying Wynwood neighborhood—a textbook indication that more of the city’s bona fides are responding to the area’s growing artist population. It’s no surprise that five museums, three collections, seven art complexes and five art fairs make use of the neighborhood’s more charming, refurbished warehouses.

Art Basel became brain food for influencers to envision a more robust infrastructure for the arts, a move towards long-term planning that began with heightened activity in the business of art that has rather quickly grown into a $1.5-billion-dollar chunk of South Florida’s gross regional product. “I think with all the international publicity we’ve received for the arts—the “Art Basel effect” that placed a spotlight on the city; the building boom, including the Arsht Center, the New World Symphony Building, the Pérez Art Museum and the new science museum set to open a year later—there is a bit of buzz around Miami building a 21st-century infrastructure for the arts,” said Spring.

From a different vantage point, The Miami Herald’s article about the NEA’s EEO tables is suddenly not so much a veiled criticism of research methodology, but an accidental commentary on the growth of an infrastructure for a world-class art scene. If viewed as a launch pad for a concentrated growth effort, the city’s seemingly low percentage of working artists sparks several questions.

First, how can local artists with day jobs convert their side projects into a sustainable lifestyle? Brazilian-born, Miami-based artist and photographer Yuri Tuma believes a potential solution lies in increasing communication between the region’s segmented art circles. “Miami is changing, but ultimately [we artists] need to think of Miami as a whole,” says Tuma, who is currently represented by Butter Gallery. “Conversations between neighborhoods are the biggest part of growing [the amount of working artists]. I think that once the conversation spreads, we’ll see a lot more happening, including more financial opportunities for emerging artists.”

At 30 years old, Tuma considers himself lucky to have reached financial stability after only nine years of producing art. During this time, however, he experienced his fair share of hurdles and distractions. He spent a financially taxing year in New York City after graduating from Emerson College, at which point he returned to Miami and rose from bus boy to manager at Joey’s in Wynwood.

A different EEO dataset backs up Tuma’s idea, albeit only intuitively. When ranking the country’s top artist populations per cities proper, Miami’s working artists make up 1.92% of the city’s workforce – a ranking of 18 out of 40, with all but three cities (Santa Fe, Cincinnati, and New Orleans) boasting larger labor forces. This suggests that Miami as a city is more cohesive among artists than the metro area at large, a trend that Spring would partly attribute to greater city-wide cultural awareness spawned by an upswing in arts-related collaboration between the private and public sectors. “Beyond money, [Cultural Affairs] believes it’s important to provide artists with the skills to manage their business as individuals, to provide tools for artists to survive through their work.”

So how is the public sector helping artists make a living, and how is the art scene reacting? While local government is too small to help every individual artist in the Miami metro area, sometimes just offering the right opportunities and sparking educational dialogues within the community is enough. For starters, Cultural Affairs’s South Florida Cultural Consortium fellowship program offers awards of $7,500 to $15,000 to emerging visual and media artists across five counties—the largest public grant to individual artists in the nation. Also, the department works with the New York-based non-profit Creative Capital Foundation to organize the yearly Professional Development Retreat, a program designed to provide individual artists with the skills to organize, plan and sustain a creative lifestyle.

In turn, a combination of public sector support, a growing infrastructure and support from an international arts community means the art scene could be starting to feed itself. Miami art duo Monica Lopez de Victoria and sister Tasha Lopez de Victoria, collectively known as the TM Sisters, are stewards of the local art scene. After nearly a decade of professional successes—major write-ups, numerous solo shows, a Murakami connection and most recently a Beck’s beer label—the sisters have developed a finely balanced system of back-up plans to combat the peaks and valleys that come with being an artist. “Over the years, there were moments when it seemed the world revolved around Miami,” said Monica. “Early on, Basel was super hyped, but then it’d turn around and we’d experience total slumps. So we’ve developed a system. We land jobs and have other ways to support ourselves outside the fine arts world. We do other creative work.” Among other things, the sisters focus on design jobs, quirky fashion products and corporate commissions when they’re not working in painting, video art, performance, costuming, electrical engineering or videogame design.

Known for their dedication to Miami, the TM Sisters, in collaboration with Loriel Beltran and a distinguished group of participating artists, impart their experience on high school artists via The LAB: Locust Arts Builders, a summer program for South Florida high school students hosted by Locust Projects. Now in its fourth year, The LAB provides budding young artists with an avenue for constructive critique and peer-to-peer collaboration during a three-week summer intensive culminating in a group exhibit open to the public. When asked if these students could potentially develop into the art scene’s next generation of influencers, Monica agreed, declaring Miami “needs wisdom—time, and, in turn, wisdom.”

The wisdom Monica refers to could point to the level of maturity cities need to become prominent cultural players on a global stage. Numerous folk theories hold wisdom as the reward for advancing age to combat biological theories that view aging in terms of intellectual regression, and they’re usually quick to unfairly rule out youthfulness on the basis of inexperience. There may be a middle ground between both views, however, because if wisdom entails applying knowledge and perceptions to make sound judgments, you need at least some time to accrue knowledge and test these judgments. So while Miami may not have to wait another century or two to build museums, craft scalable public cultural-funding programs and promote cross-generational arts education throughout the community, most would agree that we still have some growing up to do.

But how much time will it take for Miami to become a truly sustainable nerve center for artists? Just trying to quantify this feels immature. In fact, while Spring embraces Miami’s boisterousness, he recognizes it’s “still a very young community in every respect. We don’t have traditions and heritage that weigh us down, but we struggle as a result of our youth and need more time to deepen the roots we’ve already laid down for the arts community.”

Wynwood gallerist Gregg Shienbaum takes Spring’s statements one step further. The Philadelphia-born transplant, who funded his undergraduate education at the University of Miami by selling art and antiques in the early 1990s, believes that while the scene’s infrastructure is in place, Miami needs at least another quarter-century to merit global status.

“Miami still has about 25-50 years to catch up to Northeastern cities [such as New York City or Boston], but it’s getting there,” said Shienbaum. “I think you need to look at the past, and also have a past to look at. PAMM doesn’t have it yet. MOCA is great, but they’re focused on the new and edgy. Soon, however, you’re going to see museums doing Renaissance-era shows, all the way through New York Pop.” As a result, Shienbaum, like other players in the city’s scene, doesn’t fault talented local artists like Friends With You, Hernan Bas and Bert Rodriguez for furthering their careers elsewhere. But as long as Miami maintains its reputation as a vibrant, unique place to make art, their accomplishments reflect well on the area. “Some of our artists are leaving to places like L.A., but L.A. has been cool for 50 years. Miami is just starting to get cool,” he quipped.

So while data is the new raw material of business, numbers are anchored by time-based constraints and therefore shed skin like snakes. However, forward-thinking artists and their work are the currency of any art scene—timeless efforts that eventually become the canon of a burgeoning patronage. So maybe waiting around to become New York City or L.A. isn’t the key to maturity. When asked about what Miami would look like in 25 years, Spring reimagines Shienbaum’s Miami-as-latecomer vantage point, conceiving of the city’s cultural greenness as a bargaining chip in an increasingly global art arena.

More social mosaic than melting pot, Spring suggests the city’s bold, multi-ethnic solidarities collide to form a fresh urban experience, one that would allow “Miami to be known as a place where new work flourishes. If a city is going to be recognized as a great international center for the arts, it has to be a place where new work with the voice of that place is made. So if that’s what Miami is known for in 25 years, then we’ll have accomplished the work we’ve embarked upon here.”