Rashid Johnson: Message to Our Folks

Falyn Freyman

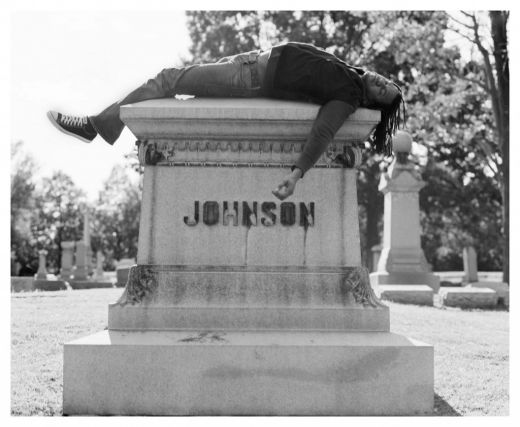

Rashid Johnson, “Self Portrait Laying on Jack Johnson’s Grave,” 2006. Lambda print, 40 1/2 x 49 1/2 in. (102.9 x 125.7 cm). Image courtesy of the artist.

The cosmic web in particular was analyzed from the perspective of topology, which is an area of mathematics dealing with the study of shapes. This is important because the web cannot be observed in 3D directly.

Rather, its existence is inferred from redshift analysis of the distant Universe. Galaxies, clusters and superclusters are removed from the images, and all that’s left is a map of their interactions…

One of the functions this structure serves is to separate one immense void—one of the eyes in the net that is the cosmic web—from the next one.

The explanation happened to call to mind an ongoing series of artworks at the Rashid Johnson: Message to Our Folks exhibition at Miami Art Museum, entitled “Love in Outer Space” (2008– ). To create the monochromatic works in the series, Johnson arranged lentils and black-eyed peas on canvas or linen, spray-painted black over everything, then removed the dried food clusters, revealing striking, abstract images closely resembling the spiraling Cosmos. Similar to the way researchers attempt to understand some of our universe’s heftiest mysteries—the Sloan Great Wall, for instance—through a process of far-removed crosschecking against complicated topological models, Johnson’s approach to his works is based very much upon creating a “map of interactions,” telling a story by exploring connections, crossing dimensions, and undergoing transformations. In a way, his works are an attempt at giving definition to these immense voids of understanding—between identity, culture, history, and memory—places where current language and models tend to fail.

One way he achieves this is through his extensive use of mirrors throughout the exhibition, which covers his nearly 15-year career. A central feature of many of his recent works, Johnson’s use of mirrors functions on multiple levels: reflecting the viewer, reflecting other works across the gallery, and offering windows of space inside which viewers can participate in alternate, duplicate, and distorted realities.

For instance, in “Body Blow” (2012), a large wall-mounted sculpture of fractured glass mirror with a Barnett Newman-esque zip of black soap and wax down the center, the viewer is invited to gaze into the work and reconsider her “now-character” ( Johnson’s name for the person she imagines herself to be for others) between holes of shattered glass and violent splatters of the eerily ubiquitous, oozing dark substance the artist refers to as cosmic slop. Made from several of the artist’s signature materials (commonplace, household, and easily accessible) there is a sense of intimacy and familiarity to the piece. After all, the West African black soap is meant to wash your body with; although the threat of its violent gestures, bullet holes and shards of glass is impossible to look past.

Belonging to another series of mirror-based works, “Run” (2008), “Promised Land” (2008), and other similarly loaded titles depict the titular phrases spraypainted in capitalized metallic lettering across a framed rectangular mirror, allowing meanings and connotations to shift as viewers contemplate themselves and the words amidst varying contexts.

Visual doubling, tripling, and multiple exposures are used again throughout the show as a means of exploring the multiplicity of identity, or what civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois referred to in his 1903 treatise The Souls of Black Folk as “double-consciousness,” “this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others.” This can be seen in “Self Portrait as the Professor of Astronomy, Miscegenation and Critical Theory at the New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club Center for Graduate Studies” (2008), which depicts a mirrored photograph of Johnson, bespectacled and clad in argyle against an Afrokitsch batik backdrop; as well as in “Triple Consciousness” (2009), one of Johnson’s sculptural shelf pieces, which displays three copies of Al Green’s Greatest Hits album, the shirtless singer gazing out at viewers with an insisting braggadocio.

Double exposed portraits like “Katie and Valerie” (2009) offer another dimension of multiplicity, in which two creamy-skinned nudes fade into a hazy, lush tropical backdrop, suggesting an inherent inaccessibility as the white women, adorned in gold chains and a braided headdress, stare unabashedly straight at the viewer. Born in Chicago and currently based in Brooklyn, Johnson has long used multimedia art to explore the rich history of African American intellectualism and popular culture, appropriating and re-contextualizing a number of images, objects, and texts to describe his own definition of Blackness. The son of third-wave Afrocentric parents (his mother was a poet and history professor at Northwestern University and his father owned a CB radio electronics store) Johnson does little to veil the largely autobiographical nature of the works, instead incorporating everything from Public Enemy and Miles Davis to Frederick Douglass and Don King as the phrasing to an intricate albeit at times problematic experience. Allowing the altar-like shelves in his sculptural pieces to perform the physical and psychological heavy lifting, Johnson seeks to “hijack the domestic space” in order to find a middle ground between two extremes of representation: the impoverished, crime-ridden lower-class and the upper one percent, the pro athletes and rap stars that dominate African American media representations.

In the tiled glass shelf piece titled “Glass Jaw” (2011), for instance, Johnson positions oyster half-shells filled with African Shea butter alongside stacked multiples of anonymous hardcovers, the title NEGROSIS emblazoned in gold down their spines, Charles Mingus’s 1957 jazz record The Clown, and a CB radio, the abandoned handset dangling off the edge of its shelf. Like the familiar yet mystifying objects which occupy the living rooms of our memories—the carpeted, smoke-filled spaces in our heads—these items are transformed into symbols meant to trigger poignant emotional cues while forcing us to question their significance within the context of the present. For Johnson, it’s an opportunity to introduce an object and have us ask what it is before we can discuss how it functions and why it functions. Just as I wondered how such an intangibly distant, mysteriously linked mesh of galaxies in space could be called a wall, the work of Rashid Johnson, unsurprisingly preoccupied with the cosmic, gives definition to Blackness by creating a vast web of connections and associations, worlds linked to other worlds by intricate and elegant forces: a hulking, loosely-defined entity, untouchable and imperceptible, yet eerily relatable to so many other patterns and structures within reach.