- Our Beloved Shithole: A Eulogy for Churchill’s Pub

- Italian Futurism, 1909-1944: Reconstructing the Universe

Jenelle Porter

Hunter Braithwaite

Charline von Heyl, installation view, Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia (2011).

HUNTER BRAITHWAITE (RAIL): Can we begin with the hierarchy between arts and crafts? What’s the current state of this debate? How do approaches to exhibition making like yours negotiate, complicate, or topple those ideas?

PORTER: It’s a complicated subject, and one that a lot of remarkable thinkers are trying to tackle. One is Glenn Adamson, the new director of The Museum of Arts and Design in New York. He wrote a great book called Thinking Though Craft. Elissa Auther, a scholar and professor, wrote String, Felt, Thread: The Hierarchy of Art and Craft in American Art. Jenni Sorkin, Jessica Hemmings, and Julia Bryan-Wilson are also working in the field.

I’m a visitor to the dialogue, which is exactly where I want to be. I’m interested in it, but the way that I make exhibitions is to put such dichotomies to the side. Whether something is art or craft, or some combination of the two, is a conversation for artists to have with their own work. For me, whether someone is an artist or a craftsperson has to a lot to do with their intention for the work. With art, one could say that ideas, the concepts, outweigh the manufacture of the object. Now this is really polemical of course, but with craft you could say that the primary impulse is the way it’s made—the craft of it.

A lot of these scholars I mentioned are trying to complicate the idea of craft. For instance, why don’t we talk about craft when we talk about Jeff Koons? Or with any number of artists who make work in which the finishing, the craftsmanship, is super-fine, and really, the focus? I’m thinking here about Takashi Murakami, for example, but in all honesty you could name dozens of artists for whom the craft of the work is at the very highest level. But then we need to consider artists who use craft as a subject in their work, for example the late, great Mike Kelley.

In terms of making exhibitions, I think defining categories remains serviceable. I do think there are distinctions in a world where everything is supposedly democratic and judgment free. For me, in terms of considering the dialogue, I like to work in the space between categories. This is how I push at hierarchies. I try to make exhibitions about ideas and objects, not about categories.

RAIL: I’m interested in the anxiety of artists connected to this debate. You mentioned in your lecture that a few artists refused to be in the ceramic exhibition Dirt on Delight: Impulses That Form Clay because they didn’t want to be typecast. But then you have someone like Sterling Ruby, who is simultaneously doing these super-heroic paintings and displaying ashtrays.

PORTER: Sterling Ruby makes really good clay sculpture, and his interest in the material comes from art therapies. What do you do in art therapy classes? You do handwork, busy work—you work with clay, you work with knitting, or papier mâché.

RAIL: That makes sense, especially with the correctional-facility element of his work.

PORTER: Sterling didn’t start out using clay; he was making a lot of things. It seems that the artists who have “bridged the gap,” so to speak, studied at art schools. They didn’t go into ceramics and textiles departments. But they found these craft-oriented materials and discovered they could be put to the service of ideas and forms. In relation to Fiber: Sculpture 1960-present specifically, Sheila Hicks and Ruth Laskey studied painting, for example. But there are also a lot of artists who went straight to fiber because they just wanted to make art with it.

“Pictures” at an Exhibition, Artists Space (2001). Left to right, works by Seth Kelly, Heidi Giannotti, Sherrie Levine, and Robert Longo.

PORTER: It’s kind of a great question that I’ve never been asked, what kind of a curator am I? Who knows, or maybe, I should say I don’t want to be a kind of curator. I’ll get back to you in 20 years. The second part of your question I can easily answer. I like to do both. I’ve been working on Fiber for about four years. But at the same time, I’ve made about ten other exhibitions. I do like the longer runway of a big, thematic group show. But I also like to make one-person shows, because I love working closely with an artist. When I’m doing a group show that’s somewhat thematic, I have a couple visits with an artist, maybe. I don’t get the in-depth time. When I worked with Charline Von Heyl to make her first survey exhibition I got to talk with her about her work for three years. I love that. Making such projects requires a certain amount of trust, and I like building that with artists. And I would say the greatest privilege of my job is to give artists opportunities, whether it’s the resources to make a new project, or merely in-depth conversations about their work.

I’ve been a curator for quite some time, and I’ve worked in institutions of different sizes. As a curator, I would say that I’m institutionalized. I love the museum. But the field has changed so much in the last 10 years. The joke is that everyone is a curator: editors, shopkeepers, D.J.’s. There’s a sign up right now in New York for curated condominiums. An ad on the New York Times website read “Curated Gifts.” You can even curate your bookshelf. It makes me nuts.

RAIL: You should see my curated spice cabinet.

PORTER: Or my scrapbook. I think we need a new title for curators.

RAIL: You’ve joked about method curating. But perhaps it’s a joke that could lead to a serious discussion? Method curating being one way people could go about things, a strategy perhaps, I was wondering how your curating has changed over your career?

PORTER: Yeah, method. Full immersion. The way that I work hasn’t changed all that much, except that I’m always responding to my institution. I was at Artists Space for three years, and we mounted four shows every eight weeks. My job was to show new art, all the time, and the rule was that we had to give artists their first ever exhibition. That was 1998 to 2001, and the situation in New York was pretty different from now. Even then, it was a much smaller art world, a lot easier to navigate. So for instance, at Artists Space there were certain types of shows I wanted to do. One of them was to re-create an exhibition.

RAIL: Which installation was it?

PORTER: Pictures, from 1977. When I was at Artists Space, it was considered the exhibition because of the artists it launched. I wanted to re-create Pictures because it was such a lodestone, so mythical, but seen by only a handful of people. You know, the most important exhibition that no one saw. Everyone remembered that Cindy Sherman was included, but she wasn’t. It wasn’t the exhibition people remembered but rather the ideas launched by it. As a young curator, this was all very interesting to me. So I recreated Pictures with as many works as I could locate and borrow. I installed the work as closely to the original installation as I could, using installation photos, even though Artists Space was in a different location. There were like 30 or 40 Sherrie Levine drawings, but I could only find four. I installed them in their original locations, which left most of the wall blank.

RAIL: I love rehanging Sherrie Levine. How perfect.

PORTER: Remaking that exhibition was so exciting. First I asked for Douglas Crimp’s blessing. Many of the original artists did not love the idea of restaging, at first. This made sense; artists hate looking back. But they ended up being really supportive, and helped me track down lost work and lost artists. And then it got kind of nutty, because the show was well reviewed, and a work by Jack Goldstein landed on the cover of Artforum. The texts about the exhibition, though, didn’t mention that the exhibition was a restaging, or that it had actually been restaged by a different curator, or why. I found that kind of reception really disappointing. Sometimes you do a project, and other people sort of run with it. The exhibition is no longer yours, and you learn from that as well. I’d also add that the exhibition I presented was named “Pictures” at an Exhibition, and included the work of four emerging artists I considered to be working within the legacy of appropriation.

Sherri Smith, Front Rang, 1976. Included in Fiber: Sculpture 196-present.

PORTER: Heidi Giannotti, Seth Kelly, a band from L.A. called Dick Slessig, and Santiago Cucullu. Now, all of those artists took different paths. Not all of them are showing their work in public. I think I have a pretty good track record with artists who drop out on purpose. [Laughter]. This is a small group of artists who make work that, 15 years later, I still can’t stop thinking about.

RAIL: There’s a weird sadness to these dropout stories. There’s this idea that you have to be in the game forever.

PORTER: And what a game! That’s a hard game to be in forever. Art is a long game, but most people are playing a short game. But back to exhibitions, lately, there have been a lot of restaged exhibitions—for example, last summer’s version of When Attitudes Become Form.

RAIL: …People run out of ideas.

PORTER: …People run out of ideas. [Laughter] But seriously, I think the impulse is the same as the one I had. You want to see the exhibition in person, understand it in three dimensions perhaps, to know firsthand what was so important about it. You learn things, like maybe it wasn’t that interesting, or it was just that interesting. Curators might be re-staging exhibitions because the field has expanded exponentially, and there is closer study of historical exhibitions.

RAIL: Speaking of exhibition making, and Hans Ulrich Obrist’s idea that the exhibition can be a laboratory, do you ever find yourself speaking of the exhibition space as some other thing? A crime scene, perhaps, or a short story, or a song cycle?

PORTER: I don’t, and that’s probably my training. I started as an assistant, and I trained-up in the old fashioned way: I learned to be a curator while working for curators. The job is that you make exhibitions with artists. The job is not about your ego. It’s not about giving artists assignments that suit the theme of your exhibition. The exhibition must be a highly-organized, carefully-considered, fully-researched, precisely-installed organism. I don’t think most curators know how to do this, and it makes me feel like a geek and a dinosaur, all at the same time.

RAIL: Are there artists who you work with time and time again?

PORTER: I’ve showed Jessica Jackson Hutchins a few times. And Arlene Shechet, who I’m currently working with on her survey. And then there are artists who I’d like to work with again, but we museum curators have to show some restraint. I mean, I’d love to work with Charline Von Heyl all the time. I’d love to work with Trisha Donnelly all the time. But you can’t just do the same show over and over.

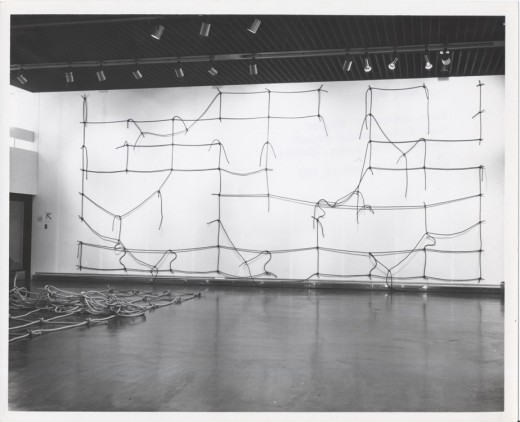

Robert Rohm, installation views, Self-titled: Robert Rohm, Anna Leonowens Gallery, Nova Scotia College of Art, Halifax 1969.

PORTER: [Laughter] Well, I think there are some good programs and some bad programs. I used to trash them, so with my typical weird, personal logic, I decided to enroll in one. Very method. I got into the Critical and Curatorial Studies program at UCLA, and because I could afford it, and because the program was run by the art department , and was this amorphous structure in which you could take pretty much any course, I decided to get my graduate degree. For two years I read art history and architecture. It was really great, but I can tell you that I had exactly one “curatorial” class. I didn’t learn anything about the work of making exhibitions. I read for two years, I had time to think, and I made a book about Stephen Prina. It was a gift.

RAIL: Two years in the library is certainly a gift, and it leads me to my next question. You currently work in Boston, a community that I imagine has many more libraries than Miami, a community which has many more art fairs. Could you compare the two cities, from your experience?

PORTER: Boston is in a situation that is probably a lot like Miami: it’s growing and changing quickly. But in probably every other way the scenes are different. Miami has this big art fair that draws seemingly the entire art world, plus every other hanger-on. You have a number of well-known private collections which function as museums. We have private, in the true sense of the word, collections. Miami has pretty strong market forces at play. Miami has many more galleries than Boston. You have a thriving artist community, with so many vital artist-run spaces. Boston needs more of these, in my humble opinion. Boston has very good art schools, like Massachusetts College of Art and Design, and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. And then you’ve got the entire educational complex of Harvard, MIT, Boston University, Brandeis, Wellesley, Tufts. The list goes on and on, and most of the universities have museums on campus. Many artists who live here, teach here. I’ve found the level of teaching and dedication to students exceedingly high. They’re also focused on their own work, and are making good exhibitions. But they’re not necessarily showing in Boston.

The ICA is sort of an outlier, not only physically but conceptually. We are not affiliated with a university, and we’re the only cultural player pioneering the seaport area of Boston. And since we consider ourselves to be a cutting-edge museum, I’d say that being on the new edge of the city is just about perfect.