- Tom Scicluna, FREE, at Under the Bridge

- The Justification of Modernist Painting: A Review of Frank Stella: Experiment and Change

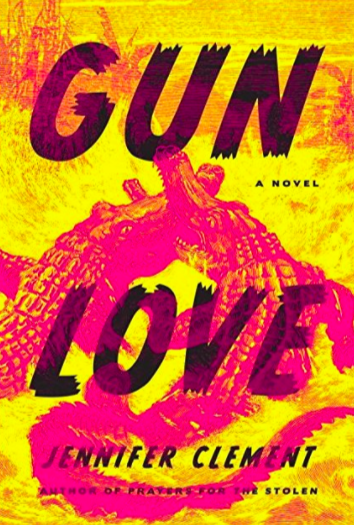

Rust and Blood: A Review of Jennifer Clement’s Gun Love

Christina Drill

Hogarth, 256 pages

Jennifer Clement is a master at creating worlds that feel like tiny dioramas —modern allegories, reflecting and responding to social issues while still feeling contained and mystical, like something you’d see inside of the world’s most ornate snow globe, or a theme park — that is, until politics invade these worlds, and these worlds become recognizable as ones that exist both on and off the page.

In her new novel, Gun Love, Clement’s narrator is nine-year-old Pearl France. She and her mother Margot live in a four-door Mercury sedan parked at the edge of a poor, remote mobile home community in Central Florida — the Indian Waters Trailer Park. Pearl calls the backseat of the Mercury her bedroom. Preteen wall décor hangs against the car’s two rear windows; the car’s trunk is filled with plastic bags of toiletries and snacks, organized like shelves in a pantry. Flowers, since there is no tabletop to set them on, are instead placed in a vase atop the hood of the car, for members of the community to admire.

It is a fragile existence, made even more fragile by the reality of Pearl’s own origins: she does not have an official birth certificate or a known father, and her mother is consistently terrified of the acronymed government organizations liable to take her daughter away from her. Also: it’s rural Florida. Everyone around Pearl for miles carries a gun.

Despite her mother’s well-to-do upbringing — “you were born in a fairytale,” Margot tells Pearl, after we learn that Margot hid Pearl in her father’s home for the first six months of her life, then fled to avoid the physical abuse she endured from him — Indian Waters is the only world Pearl has ever known. When Pastor Rex, the shady leader of the local church, begins asking members of the community to donate their guns to Jesus (so he can, secretly, profit off flipping them), the illegal operation opens the doors to tragedy in Pearl’s backyard.

Clement is able, between lines of sparse, poetic prose, to tell us everything. Pearl describes her mother as “a cup of sugar. You could borrow her anytime,” foreshadowing her fatal relationship with a man named Eli. When Pearl and Margot sit and listen to drunk men rain bullets over the water while hunting for alligators, Margot says, “There they go again. They’re killing the river,” and one understands that more than the alligators are being hunted.

In this way, Clement’s fictional no-mans-land in Florida becomes all of America, the “land cleared over Native ground,” an example of what gun violence does to the communities they infiltrate — ruining, decimating and depopulating them. Pearl, despite her environment, endures, even as she is pushed through Florida’s foster care system where she becomes just another “shooter,” ironic CPS slang for children orphaned by gun violence.

After unspeakable tragedy, Pearl herself disappears, without any announcement or understanding of where she might end up next. As Pearl leaves the state of Florida for the first time, she observes, “Abandoned homes in trailer parks were everywhere — all across the United States of America.” All her life Pearl has watched people join, then suddenly flee, her community. But even as Pearl seeks somewhere to call her permanent home, the horror and reality of man’s obsession with weapons follows her as does the flawed notion that carrying a gun equates to power.

In Gun Love, Clement has written an inspired and haunting story, a tome of anti-gun activism that doubles as a paean to the countless gun-ravaged communities across America suffering the same trials as the women of Indian Waters. The story is both gentle and relentless, creating the experience of a moving fast read. At the beginning of the novel, during an intimate scene between mother and daughter, Margot tells Pearl, “There are over one hundred thousand people missing in this country. If they can’t find those people, how are they going to find us?” In Gun Love, those who are “found” are discovered as mere bodies, too late to be returned to those who love them.

Christina Drill is a fiction writer in the University of Miami’s MFA program and the production editor of The Miami Rail. Her writing has been published in New York Magazine, Chicago Quarterly Review, and Broadly (VICE).