Decidedly More Than Delirium: The 55th Venice Biennale

Emily Mello

Camille Henrot, Grosse Fatigue, 2013. Video installation (color, 13 min). Project conducted as part of the Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship Program, Washington, D.C. Special thanks to: the Archives of American Art, the National Museum of Natural History, and the National Air and Space Museum.

he turns the leaves over rapidly…

“…it is sublime—that science! for the world, as a philosopher once explained it to me, forms a whole of which all parts mutually influence one another, like the organs of one body. it is this science which enables us to know the natural loves and natural repulsions

of all things, and to play upon them…. therefore, it is really possible to modify what appears to be the immutable order of the universe.”

…

Anthony turns toward his cabin; and the stool supporting the great book whose pages are covered with black letters seems to him changed into a bush all covered with nightingales.

Gustave Flaubert called The Temptation of Saint Anthony (1874), “the work of [his] entire life.” As though a codex from which all other books flowed, he rewrote it multiple times over three decades, starting up again with particular verve before embarking on each of his more celebrated novels. With a later abandoned idea that the narrative would be a theatrical production, a large book under torchlight, the Bible, remains a performative element and a stage itself, as indicated in a series of jeux de théâtre. Ascetic Anthony, tired from fasting and monotonously weaving mats, recites scripture and grasps for a divine shield from disorder. The hallucinating monk holds fast to a righteous life by withdrawing in solitude to read a single book that in fact unleashes a procession of monstrous temptations—a pantheon of blasphemous beasts and gods; Satan disguised and casting doubt as the embodiment of science; the Queen of Sheba who offers riches and lust. In his introduction to the Temptation, “La Bibliotheque Fantastique” (1967/77), Michel Foucault noted that Flaubert too invoked madness to describe his active and absorbing labor, one that included a vast accumulation of material to form his single “book of books”:

I spend my afternoons with the shutters closed, the curtains drawn, and without a shirt, dressed as a carpenter. I bawl out! I sweat! It’s superb! There are moments when this is decidedly more than delirium.

For The Temptation, Flaubert read at least 134 books on ancient history, world religions, astronomy, and geography and corresponded with an archaeologist. That’s nothing compared to the 1,500 he consulted to write Bouvard et Pécuchet (1881), his story of two copy clerks turned walking bourgeois encyclopedias in their absurdly endless search for knowledge. Foucault argued that Flaubert opened a new space for the imagination, with visions wrought not from a dark night of the soul, but from vigilant research and from his reproductions of images from books rendered with precise and supple language. Visions flowed from the interstices of books within his ad hoc library. For Flaubert and all those that came after in intertextual pursuits, Foucault proclaimed, “The library is on fire.”

Removed in a fever of studied or apophenic connection, the inner life of an artist making sense of the overwhelming and infinite, forgoing health and excused from social manner, submissive to an obsession powered by an internal drive, or chimerical force: this romantic stereotype seems to hold timelessly, even if its appearance in the discourse falls in and out of fashion. Even in the coolest times, there is a modicum of eccentricity that can be branded before it becomes untenable to the business of contemporary art. The web may be a place that demystifies, but it is also a platform where many artists, as with everyone else, continually consider what to leave shuttered and what to parse out. More regularly, we encounter the stream of endless information and shifting post-human identities existing as websites and profiles, than the mythic figures that spring from palpable theatres of knowledge—the book, the library, the archive, the museum, the cabin in the landscape, or the unearthed basement collection of the shut-in.

The language of possession, alienation, pseudo-schizophrenia, mystical collectivity, and the infinite world of too-muchness are not unique to this age, even if exacerbated by the speed of hyper-connectivity and the serendipitous search engine. Perhaps there is a difference, that “we no longer partake of the drama of alienation, but the ecstasy of communication,” where the scene has largely been replaced with the screen, as Baudrillard concluded in 1987, before the Internet as we know it existed.

For many, the world has always been too much, but the impulse to pluck form, meaning, and understanding from the abyss has persisted with varying levels of belief in possibility and impossibility—both of perfection and imperfection and of subjectivity and objectivity—that makes knowledge at turns an instrument of power, a means to transformative change, and a fleeting game of dizzying fascination. How do we factor the inner life of the imagination engendered by the process of looking out, researching, recording, gathering, and reading; or by looking within, tapping the subjective unconscious or the spirit moved? In these politically tumultuous and technologically cool times, is examining inner drives not reserved for the biopics, rumored anecdotes, and nostalgic romance, rather than a framework for a global exhibition of contemporary art?

The 55th International Venice Biennale diverges from past Biennales in how it acknowledges the futility of gathering the most globally relevant work of the moment in one city, even with the massive main exhibition spaces of the Central Pavilion and the Arsenale, along with the scattered national pavilions. The “how” of The Encyclopedic Palace, the international exhibition, does not merely apologize for exclusions, but offers a researched point of view that veers from the implied directive. Biennials may be exhausting, but never exhaustive in their presentation of contemporary art. No matter how sprawling, they will always seem a frustratingly slim volume drawn from a much larger shelf, if evaluated by their comprehensiveness. Instead curator Massimiliano Gioni’s meta-approach includes more than contemporary art, assembling art and artifacts from the past and blurring the distinctions between artist and outsider, while stressing the inner worlds of those who create external forms.

Marino Auriti, Il Encyclopedico Palazzo del Mondo or Encyclopedic Palace of the World, ca. 1950s. 55. Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte, Il Palazzo Enciclope- dico, la Biennale di Venezia. 55th International Art Exhibi- tion, Il Palazzo Enciclopedico, la Biennale di Venezia. Photo By Francesco Galli. Courtesy la Biennale di Venezia.

Instead, an enchantment with the otherness and inner lives of those in rapt pursuit of universality rises to prominence. Conservation concerning the fragility of an open book covered in handwriting and marvelously dense color illustrations does not pragmatize the glow casting drama on Carl Jung’s magnum opus. The exhibition in the Central Pavilion begins with The Red Book, the renowned psychotherapist’s personal cosmology taken up to deal with his own psychotic hallucinations. Shared almost exclusively with his family, friends, and heirs until its public debut at the Rubin Museum of Art in 2009,the book appears as a sacrosanct relic in the middle of a dim circular gallery. The two fabled objects, the palace and the book, that set the stage for each hall cause one to speculate if the desire for the myth and the scene emerges from a fatigue with the slippery images of the screen.

Roger Caillois, an ex-Surrealist too empirical for André Breton, saw microcosms in his rock collection, which occupies a vitrine that feels as though it could be in a natural history museum, were it not neighboring photographer Hugo A. Bernatzik’s collection of drawings from tribal societies in Melanesia. Besides joining the collections of those who were themselves image-makers, the affinity stretches from what Caillois called the “universal syntax” that he saw in the patterns of stones to the less mystical understanding of Bernatzik’s drawings, many by those whom he first introduced to pencil and paper, adding to the intrigue of their (near) universal pictorial strategies. Bernatzik, an ethnographic photographer who once made a colonial handbook for Africa, was also influenced to collect his “primitivist” drawings by a pseudo-scientific idea of microcosm—specifically, 19th-century German biologist Ernst Haeckel’s theory that tribal societies represent an embryonic stage in development.

Many moments like this raise the question of whether or not the exhibition underscores the less magical and more menacing aspects of knowledge production and circulation by combining far-flung materials, or dilutes the reading of individual works in its imaginarium. Further blurring the distinction of intent and drives, the same gallery contains images not collected, but divinely received, such as Shaker gift drawings from 1854. A former rubber-plant technician turned visionary medium in China, Guo Fengyi’s profusion of fine color-ink lines form mythological creatures on rice paper scrolls, also present in this gallery. Fengyi, who died in 2010, denied authorship of her drawings, saying she was compelled to draw “to know.”

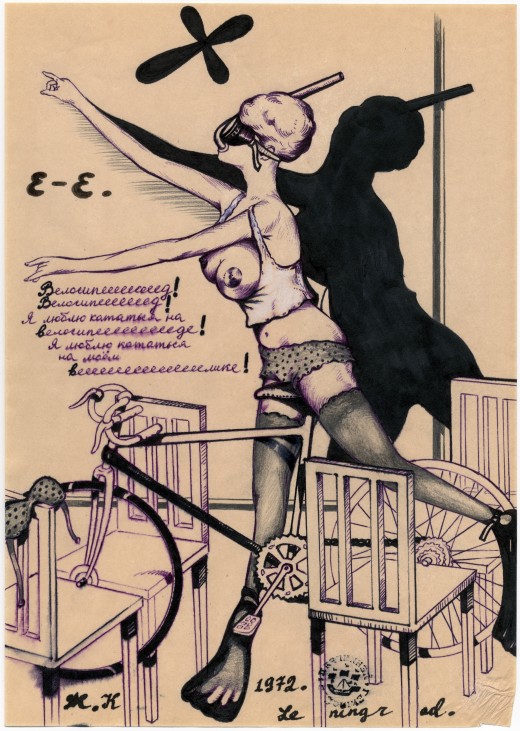

There are numerous additional examples of the unearthed work of figures who, if outsider is an inadequate term, in any event produced images with motivations that were wholly other than a desire to be brought inside the contexts of art. A preciousness pervades these hand-drawn or crafted miniature worlds made with accessible materials: Emma Kunz’s intricate diagrammatic healing drawings, begun in 1939; the “Leningrad Album” of then-teenager Evgenij Kozlov’s erotic drawings from the ‘70s discovered two decades later; and artist Oliver Croy and architecture critic Oliver Elser’s presentation of their junk shop find: “The 387 Houses of Peter Fritz (1916-1992), Insurance Clerk from Vienna” (1993-2008), an inventory of architectural housing styles in model-form meticulously crafted with everyday materials.

The Encyclopedic Palace shares some curatorial reference points with 2012’s dOCUMENTA (13), including the archive, the index, and the cabinet of curiosities. Within a post-colonial imagination, the advent of the 17th-century encyclopedic cabinet has a mixed history of promiscuous combinations that at once wondrously liberate materials from their later developed, now familiar classifications, while assigning all to other-worldly exploration and capture; A taxidermied crocodile might stare down a mermaid’s hand neighboring a landscape painting, a ceremonial object or in the most overtly objectifying examples, real or depicted human “oddities.” Whereas dOCUMENTA (which I did not see) is said to have emphasized specificity and political realities of past and present, here, this tension of individuality and universality comes to the fore when the interest in the mystic and the psychic brushes up against the “insider” contemporary artist who assumes less the role of the dreamer and more that of the discoverer.

Evgenij Kozlov (E-E), Untitled (The Leningrad Album, No 204), 1971. Ink, ballpoint pen, pencil, crayon on paper, 29.7 x 21.2 cm. Collection Kozlov & Fobo, Berlin.

More often than externalizing personal cosmologies, psychologies, or their own world of dreams, as is the revealed backstory of the outsider artists, and artists from the past, the contemporary artists express a fascination with the construction of knowledge itself and with the visions of others. This is perhaps the differentiation and conflation of Flaubert’s feverish work and the hauntings of his St. Anthony. A researched political critique of subjective histories strongly emerges from the work of artist Rossella Biscotti in other contexts. But here, grouped with wagons handcrafted from found materials by Brazilian visionary artist Arthur Bispo do Rosário who lived in an asylum; the drawings of Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, a mystic and founder of a religion in the Ivory Coast; and the colorful, illustrative tapestries of celebrated Senegalese artist Papa Ibra Tall, who created his own style influenced by exploration of western traditions; something is lost in the unifying mist. In the case of Biscotti, the political implications of her sound sculpture, the recorded voices of female prisoners on a Venetian island telling her their dreams, weaken. In many ways the exhibition asks the question that the Internet relentlessly asks itself every two seconds: Are we really more connected than ever? And answers every two seconds, tempting to think so, but I’m not always so sure.

Harun Farocki, Transmission, 2007 (video still) video, color, sound. 43 minutes. Courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York.

Continuing to contrast with the abundance of handmade precious materials, hands themselves enter the frame in several other videos, both in The Encyclopedic Palace and the pavilions. Camille Henrot’s absorbing “Grosse Fatigue” (2012) layers endlessly-opening desktop windows with videos, photos, and scrolling Wikipedia pages into a single channel video. Workers at the Smithsonian museums (the closest realization to Auriti’s dream, where Henrot was in residence) hold up documents, pull open drawers and fondle taxidermied birds. The pursuit of knowledge moves back and forth from images of what feels at times a dated, creepy mausoleum, to an ecstatic fetishization of what can be held onto in an ever-expanding universe. Feminine hands manicured to coordinate with the saturated hues of commercial photo backdrops sensually turn the pages of books filled with yet more images, roll an orange back and forth, peel an egg, and plunge into her underwear. A percussive soundtrack with a man’s voice reciting creation myths with a repetition of “in the beginning” and “and then… and then… and then…” compounded with the piling images, makes the flooding screen of information both fatiguing and sexy.

Farocki and Henrot’s work are more typical of the contemporary artists in the exhibition, who among them use

the lenses of ethnographers, documentarians, diagrammers, and researchers whose visions are created through their forefront awareness of the mutability of semiotics and subjectivities. For some, the approach is more directly political: In the genre of hands holding things, “Letter to a Refusing Pilot” (2013), not in Gioni’s exhibition, but in the Lebanese Pavilion, examines the circulation of images in knowledge production born from conflict, while telling an affecting, fragmented history of a school bombed in 1982. Hands manipulating archival clippings and his family portraits enter the frame of Akram Zaatari’s film projection, recovering a profound past as legend and network of complex truths. Bouchra Khalili, whose work seems conceptually and physically separate in its out-of-the-way location, prefers to film the liminal conditions of immigrants in Genoa who ultimately assert, “I am here,” rather than the liminality of dream states seen elsewhere.

How do we reconcile these political realities with the presence of the enlightenment model of the cabinet of wonder, the outsider visionary, and an exhibition with a predilection for the withdrawn and inward look? Are the latter the elements of the scene perceived as safe landings and proxies for the unbound “insider” imagination to play upon, when it is otherwise negotiating the screen of the contemporary image world? Baudrillard asserted that communication replaces theatres of knowledge, where there is no longer a sense of uncovering the hidden, but only the “seduction of appearances.” The desire to know and examine past formulations of order may be a nostalgic longing for the now- mythic origins of such possibility; an ambivalent longing for decidedly troubling words like authenticity, discovery, and universality, even when participants in contemporary-art discourse are well-enough versed in the paradigms of power to keep the imagination in check. If we are to consider drives, might these desires arise in response to the screen of alterable images and infinite information? If Flaubert is one indication, similar conditions have long existed, even in the library, but are now carried in the pockets of those privileged enough to globetrot the world in search of art, knowledge, meaning, or connection. The Encyclopedic Palace offers an image of the world explored and assembled as a false retreat from the fatiguing screen and fleeting solace from the fear of getting lost in its surfaces.