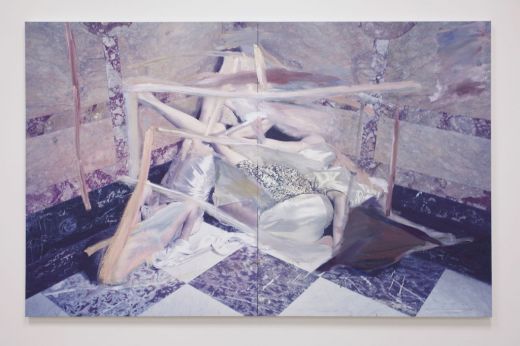

Loriel Beltran, Specola, 2013. Oil on Glicee, 80 x 50.”

Guccivuitton

In his solo exhibition Rococo Chanel, on view at the aptly titled gallery Guccivuitton, Loriel Beltran examines the visual language of taste and luxury. The show features a series of paintings that directly engage with the photographs one finds littered in the pages of fashion magazines. Beltran appropriates images from highly sexual advertisements and fashion shoots and presents them in a jumble of tan body parts. The pictures are then enlarged on giclée from scales ranging from 30” x 40” to 80” x 50”. The photos are smoothed over in creamy, asymmetrical brushstrokes, thereby rescuing the photos from the rigidity of perfect contours.

Rather than questioning the implications brought on by these ads, Beltran exhibits a willingness to accept and visually complement the existing image. Beltran’s sculptures however, obliterate the original subject in a manner that becomes much more charged. His pair of concrete and marble columns, standing 60 inches in height, are a unique blend of modern geometrical form supporting an abstract sphereof swirling lines. Inspired by the mélange of elements gracing the driveways of Miami’s many estates, the columns appear as remnants of a dilapidated empire: entry statues decapitated, faux marble crumbling. In invoking the Rococo—a style characterized by its whimsical, delicate, and feminine form—not to mention a fashion brand long considered the pinnacle of haute couture, Beltran situates his work in discourse with the highly contested style. The Rococo was born in the aristocratic apartments and noble salons of the eighteenth century. During the reign of Louis XV (1715-1774), the Rococo delighted viewers with its ephemeral and coquettish charm—conjured up through swirls of paint that flowed beyond the canvas to the apartment walls, furniture and adorable snuffboxes. The fêtes galantes of Jean- Antoine Watteau imagined worlds where immediate pleasure was seamlessly achievable. But as the taste for playful pastels and sensuous curves yielded to the more serious compositions of Neoclassicism, the Rococo absconded from the limelight of France’s Royal Academy.

Scholars have observed the association of the Rococo resurgence with burgeoning markets; the Rococo revival around the boom years of the late 1980s is just one example of the style’s attachment with market forces. After the fall of France’s monarch, the excessive ornamentation of the Rococo, however beautiful, became a marker for conspicuous consumption, commonly targeted as feminine. It is interesting therefore to see how Beltran has deployed a Rococo-like formula. His “Something Revival,” which depicts a gold-threaded oriental sofa painted with beautiful shades of gold and beige, demonstrates how this is not only a conversation about painting and decoration, but raises issues of consumption given its source and unabashed sensual nature. The hodgepodge ornamentation of his concrete sculptures, though quite pleasing, hints at a stylistic history vanished in an era of mass production. One can observe their concrete counterparts along highways where nursery-like plots sell fountain angels, lions, and children coupled in courtly romance. Beltran’s work shines light on a fragile and frivolous age, yet if we allow ourselves to indulge in the painterly qualities of his work, the creamy brushstrokes dissolve a messy reality just beneath its surface.