Robert Winthrop Chanler: Discovering the Fantastic

Annik Adey-Babinski

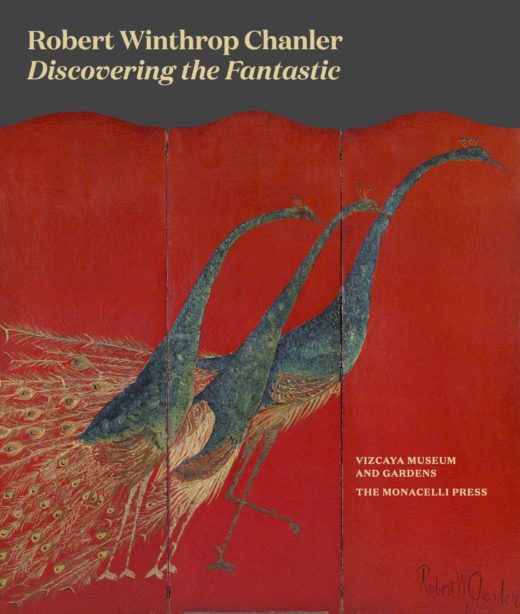

Robert Winthrop Chanler: Discovering the Fantastic Gina Wouters and Andrea Gollin, eds. The Monacelli Press and Vizcaya Museum and Gardens, 256 pp.

Allow me a brief, indulgent review of Chanler’s life. He was one of the ten Astor orphans, members of an elite New York dynasty raised by various caretakers at Rokeby, the family estate in the Hudson Valley. Chanler made headlines in his youth for marrying Lina Cavalieri, a Parisian opera singer, and divorcing her less than two weeks later. When James Deering—who built the Vizcaya estate in Miami and was a patron of Chanler’s—asked him about the marriage, he reportedly said, “It cost me a million but it was worth it.”

A prolific and fevered painter, sculptor, set-designer, and decorative artist, Chanler played a pivotal role in starting not one, but two modernist art collectives. Later in life, he had not one, but two live-in lovers who received stipends from his family accountant. They took turns hosting parties in his New York City home, “The House of Fantasy.” A policeman once called to quell one of the fêtes reportedly ended up behind the bar, mixing drinks beside Chanler, who wore his hat.

As a result of a post-war preference for realism over decorative art, Chanler was mostly forgotten after his death in 1930. In his heyday, he was known for his work with screens and murals in private homes in New York. However, he also dabbled in stained glass, portraiture, and sculpture, usually working on large interior spaces. Chanler’s work is often referred to as fantastic. Imagined ecosystems in which Florida alligators swim in the Hudson River and new constellations appear in the skies were a hallmark of his work.

Increasingly, Chanler is recognized as a contributor to the Gilded Age of modernism, in part because the divisions between so-called decorative and fine art have collapsed. As Frank Mateo writes in “Preserving the Fantastical,”

Would one label Klimt, Klee, or Vuillard as “decorative artists,” given their deployment of ornament, color, and pattern, or Whistler as a decorator given his obsession with carefully orchestrated interiors? [ . . . ] It is within this renewed attitude that Chanler’s work should be revisited.

This revisitation developed when a few dedicated scholars came together in 2014 for a national conference on his work. The event was hosted by Vizcaya Museum and Gardens, which houses two Chanler commissions: Vizcayan Bay—a free-standing screen—and the mansion’s undersea ceiling mural over the swimming pool grotto. Discovering the Fantastic emerged from this conference. A collection of criticism edited by Vizcaya curator Gina Wouters and freelance writer Andrea Gollin, it is the first in-depth survey of his life and work in more than 80 years. The book includes 6 major essays about Chanler, his life, his work, and his home; 200 illustrations; and preservation notes from Lauren Hall, Vizcaya’s conservator.

While the book covers in delightful tabloid detail the personal side of Chanler’s life, the authors also do the categorical work necessary to recover his impact on modernism. Laurette E. McCarthy, author of “Setting the Stage: Chanler and the Armory Show,” does painstaking research into the twenty-six pieces Chanler included in the Armory Show, proving that his contribution was more than any American. Aside from his talent, the author links this achievement to Chanler’s connection to the elite women of New York who formed the Association of American Painters and Sculptors (AAPS) that put on the exhibition in 1913. After all, as Wouters writes in “Chanler and the Gilded Age,” “A year before the commission for Vizcaya’s swimming pool grotto ceiling, the Richmond Times Dispatch declared ‘Mr. Chanler’s weird screens the newest fashionable fad’ and asserted that the ownership of his work was a ‘virtually accepted proof of wealth.’”

Chanler’s works are notoriously difficult to conserve. Hall explains that misguided overpaints, a lack of color photography, and structural and environmental factors at Vizcaya pose significant challenges for restorers. If you take a walk through the museum gift shop and study the mosaic ceiling, you can imagine how storm surge waters during a hurricane would threaten the gessoed plaster casts of shells, Hudson River sturgeon, and fantastical creatures Chanler pieced together for Deering.

Since Chanler’s work was mostly for private homes, his own home functioned as a portfolio. In Lauren Drapala’s “Building the House of Fantasy,” readers learn Chanler’s home, with its meticulously designed rooms, became an icon of modern life. In the 1920s, Chanler had the Edison Company create a heating mechanism for his aquariums, and he kept pools for the flamingos and peacocks he represented in his work. This Animal Annex occupied the back of the home and the basement, and it was Chanler’s source for his loose representations of nature that, according to the authors, had “less to do with natural habitat” and more to do with “color and line.”

As this collection set out to prove, Chanler influenced modernism with his fluidity between high and low, representation and imagination, and screens and sculptures. Robert Winthrop Chanler: Discovering the Fantastic is a welcome contribution to conversations we have about making art today—and what it means to call yourself avant-garde in 2016 given the modernism that came before us.

Annik Adey-Babinski is a writer living in Miami. She was one of Jai Alai Books’ Eight Miami Poets.