T. WHEELER CASTILLO AND EMILE MILGRIM with Monica Uszerowicz

Monica Uszerowicz

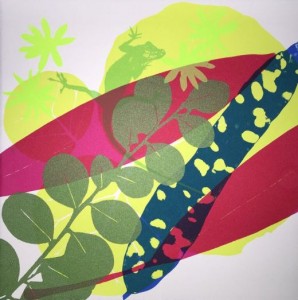

T. Wheeler Castillo, Terrazzo, 2014. Screenprint, 28 x 28 cm. Printed by Emile Milgrim and T. Wheeler Castillo at Turn-Based Press

It is with slightly less sentimental underpinnings that Emile Milgrim, musician and founder of the record label Other Electricities, and artist and Turn-Based Press co-director T. (Thom) Wheeler Castillo, created Archival Feedback, an aural and visual project documenting Florida’s unique landscape: its sounds, its feel, and the kaleidoscopic interpretations thereof. Supported by the Knight Foundation, Archival Feedback has been in development for a long while, even in ways unbe- knownst to its makers. Both grew up in Florida, then lived and studied in Portland, Oregon, where they found themselves unwittingly influenced by the warm feelings of their home, the colors and memories weaving their way into their respective crafts. Archival Feedback might be a sonic map, but it is also an unintentional love letter, a manifestation of the inherently resolved act of coming home.

The record’s A side features field recordings—a Biscayne Bay drainpipe, an ice cream truck in Little Haiti, the clinking of seashells in Sanibel—with its F side (“Feedback”) showcasing the work of Floridian sound artists who addressed the field recordings as they saw fit: remixing, reworking, responding. The five prints included with the record are each a personal project themselves: for example, Terrazzo, made up of several layers of color, is designed to invoke the memory, shared by so many Floridian children, of cooling the body on the cookie-patterned floor; Field Notes, a composite “landscape,” showcases a series of dates, including the record’s release, the first airdate of Captain Planet and the Planeteers, and the year Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda was shipwrecked in the Florida Keys.

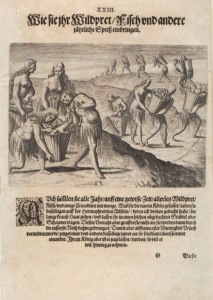

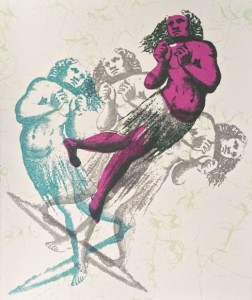

Suspended In…, the most whimsical of the set, references engraver Theodor De Bry’s sixteenth-century Grand Voyages. De Bry’s documentation of the Timucua tribe’s “third sex” is pejorative in nature; in Suspended In…, an androgynous or trans body, having been subject to interpretation by white colonialism, is set free, dancing and floating. It is through this same process that Milgrim and Castillo document Florida, both transforming and archiving it for future generations’ own understanding and retelling.

In a round-table discussion in Little River, during which the sun set and filtered through a melodramatically lush foliage surrounding Castillo’s house, the two discussed the means by which the project’s audio and visual components were created.

T. Wheeler Castillo, Natives Only, 2014. Screenprint, 28 x 28 cm. Printed by Emile Milgrim and T. Wheeler Castillo at Turn-Based Press

EMILE MILGRIM: Some were intentional and some were found by happenstance. We had dozens of ideas and took hun- dreds of recordings, with different mics and angles and at different times of day. Sometimes weather was a determining variable in the end result. We wanted the recordings to be as immersive as possible, to the point where the listener would feel soothed, anxious, disoriented, or curious if they listened with headphones—this is especially true of the binaural approach used on two of the final tracks.

RAIL: In an interview with Liz Tracy, she says that Thom found that the most “‘in-depth way’” to convey Miami was through sound. Why is this true?

MILGRIM: Some people remember through sound and some are triggered by it in a seemingly unconscious way. Others are more selective listeners. Then you have voracious, active listeners, like me and Thom, which is why this approach made sense to us. Some of the sounds we captured were intended to stimulate and interest the aforementioned types of alternate, nonlisteners. For example, the dominoes recording is something I’ve heard in my neighborhood almost every day for the past three years. I know it drives some neighbors crazy, and I know others tune it out or don’t notice it. I was really interested in the intensity, the jagged rhythms and patterns of that aural experience. Listening to that recording out of context—in headphones in a gallery, for example—has revealed the further complexities of those sounds.

RAIL: I want to talk about some of the images with you, especially Suspended In…

T. WHEELER CASTILLO: Theodor De Bry published Grand Voyages in 1556. It was the first book published in Europe documenting the discovery of the Americas. Maps had been discovered, but not images of the people inhabiting the country. De Bry never set foot in the Americas. He based it off of someone’s journals—a guy named Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, who didn’t even talk to De Bry. De Bry went to his widow and bought the journals.

RAIL: It’s like a game of telephone.

CASTILLO: It’s totally telephone. Not only did De Bry not have any firsthand interactions with the natives, he also had to fill in a lot of gaps, because there were so many unanswered questions. You know he improvised, because these images are supposed to be taken from Florida, and look at how hilly it is. A lot of it seems very Protestant. He says, “the Indians come to an agreement among themselves which illustrates the harmony that exists among them”—totally projecting, and also kind of implying how easy it will be to colonize them. The engraving that moved me the most was Employment of the Hermaphrodites, an image of the Timucua tribe. I did find a few queer writers who wrote about them, because they’re clearly queer figures or representative of a way these people dealt with those who did not identify as male or female. We know that various tribes in the Americas had this place in their society. Some were positive, some weren’t so positive.

RAIL: And I know you selected these images because of printmaking history, and for numerous other reasons, as well.

CASTILLO: After living in Portland, I moved back to Miami to a house that was right off the bay. I grew up on the west side of US-1, completely disconnected from the ocean. I couldn’t wait to leave Miami. But while I was in Oregon, so much of the visual work I was doing referenced qualities of Florida. I was in a gray place, and all of my work was about light, or open spaces—at least this is what people were reading from the work. I was speaking a vocabulary unfamiliar to people from the Pacific Northwest.

I moved back and was curious about this unconscious expression of the landscape. Around 2012, when I told Emile we should make a record, it was also the beginning rumblings of this five hundredth anniversary of Florida, of the Spanish Conquest—a myth, because Ponce De Leon barely touched it. It felt like it was more PR than an important date to celebrate. In that reaction, I came across Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda’s memoir. When Fontaneda was traveling from Cuba back to Spain, he was ship-wrecked in the Keys; everyone on the ship died except him and his brother. They were enslaved and he spent seventeen years living among various different tribes. I think the most beautiful part about reading his memoir is the first line of the second memoir (he actually wrote the memoir twice): “Memoir of the things, the shore, and the Indians of Florida, to describe which, none of the many persons who have coasted that country know how to describe it.”

Theodor de Bry, Bringing in Wild Animals, Fish, and Other Stores from Philadelphia

RAIL: There is a unification happening with the terrazzo print, the freed figure, the blue of “Raga.”

MILGRIM: It was a lot of back and forth, talking about these things, which is not something I was used to in creating. I usually work with sound and I work alone, or in a group with a very straightforward context. It’s very methodical—a numbers thing or a puzzles thing. This was a different experience; it was challenging, but very evocative and helpful in being able to break out of a methodical way of working. It was far more conceptual than what I’m used to.

RAIL: It’s probably harder to work in a way that allows for unfolding and movement.

CASTILLO: I might get in trouble for this, but I think that’s tied to a way a lot of printmakers work. Because what we do takes a lot of steps, we have to prepare—there is a clear method. We cut all this paper by hand; we mixed the colors. Sometimes I would mix the colors and not be happy with it, initially.

RAIL: Was making the record like that, too?

MILGRIM: I didn’t think the recording and capturing process was like that, but a lot of the editing was: having to go back and listen to things and make selections and, once those final selections were made, pulling out the pieces that were going to be on the record and further editing those down for fidelity’s sake. I never want to hear those field recordings again. Like the Everglades one—I probably listened to it three hundred times trying to get these little distorted wind pieces out of it. I felt insane.

RAIL: Everyone is going to experience Archival Feedback differently. Forgive me if this is redundant, but what is your own read on the project itself?

MILGRIM: I’ve always experienced things sonically. A lot of the memories I have are tied to sound. There are so many sounds in this place that aren’t day-to-day sounds elsewhere. Like the different types of water: rain sounds, bay sounds, river sounds, ocean sounds, flooded street sounds. There are other, culturally derived sounds—the dominoes are a big example. There aren’t a ton of cities in the United States where you can go multiple places and hear people playing dominoes, speaking different languages. It’s normal to us because we’re around it all the time, but I tell people the story about how my neighbors play dominoes every single night for four hours, and they’re like, “That’s not a thing.”

It becomes a part of your memory and your experience, even if it isn’t your culture, which is also really interesting to me. I didn’t grow up around that in my immediate environment; it’s always been peripheral. But there are those peripheral sounds that resonate with me, and when I was living in Oregon for so long, I noticed their absence. It was weird. Capturing that was a way of me remembering but also further exploring it, and being able to show it to people.

CASTILLO: Also, did you get to hear the single “11th Street Train Whistle”? We’ve been selling it as a tape; it’s not on the record. At the 11th Street Metromover stop, there’s a metal sign drilled into the fencing with just enough space, so when the wind is fast enough, a whistle happens. This was the one I would’ve felt like a failure for not being able to document. One day, the wind was strong enough for us to get it, but once it’s over nineteen miles per hour and it’s rainy, the platform becomes really dangerous. The guy who responded to the recording is my buddy Nick Ortrotasce, who is also from Florida, who lives in Sarasota. He lived in Oregon for a few years and then moved back—it’s another Floridian perspective. Every single artist on that record, on the F side, is from Florida.

MILGRIM: We assigned these things, not entirely arbitrarily, but with David Font-Navarrete [io.ko], I gave him these domino sounds, and it turns out, fifteen years ago, he lived in the same neighborhood and made a very similar recording. We gave David Brieske [Fsik Huvnx] the traffic sounds and he was like, “I’ve been making these same exact traffic recordings for years now.” It was really cosmic, the way these things worked out.

RAIL: It feels Floridians have been, more than ever, addressing our relationship with the land, due to problematic issues. This work has nothing to do with the landscape in that capacity, but I am wondering if such ideas ever came up as conceptual concerns.

CASTILLO: We did say, in another statement about the project, that it was an attempt to document this ever-changing landscape. We were thinking about past, present, and future—this idea that we should go back and, every single year, attempt to record these same recordings and see the difference. That would be true fieldwork. And maybe that will happen.

MILGRIM: There’s a whole other project in the works.

CASTILLO: There’s a Phase III—Phase I was the record, Phase II was the production of all of this, and Phase III is creating an archive of sound that anybody can access, as well. I love anything that promotes a form of productivity. This attempt to docu- ment something that is constantly shifting and changing isn’t an alarmist reaction. This is more like accepting of and maybe being influenced by this impending change. I’ve accepted the sea level rising.

MILGRIM: Isn’t it like most things, at least growing up down here? I’ve always felt like there is a dichotomy—people who notice and care, and people who are like, “What’s happening? I drive my car five billion miles and blast my AC even in the winter and I don’t recycle.” Like, “More BMWs now!” A lot of that stuff isn’t even people who are from here. But some people from here aren’t saying no—they’re not voting, they’re not caring. They want to be as comfortable as possible and it ends there.

CASTILLO: Who were the first anthropologists? They were documenting cultures that were perceived as “dying.” That’s its problematic history—but the fieldwork and going out and collecting, that has an influence on me. There was another recording that didn’t make it onto the record; it will hopefully live in the archives, on the Internet. It was taken at Ten Thousand Islands; I went camping with Felecia Chizuko Carlisle, and another artist, Packard Jennings, and we slept maybe one hundred feet from the dome homes on Cape Romano. I have recordings of that shore. Those submerged homes. . .

MILGRIM: An apocalyptic utopia.

CASTILLO: I can’t wait for it, honestly. Everyone is going to live in boats and the corals are going to take over.

T. Wheeler Castillo, Suspended in…, 2015. Screenprint, 30 x 25 cm. Printed

by Emile Milgrim and T. Wheeler Castillo at Turn-Based Press