- Some Irreverent and True Early Conceptions of Florida As Under-explained Reasons For Why This Part of the World is Consistently and Continually Absurd

- My First Bikini

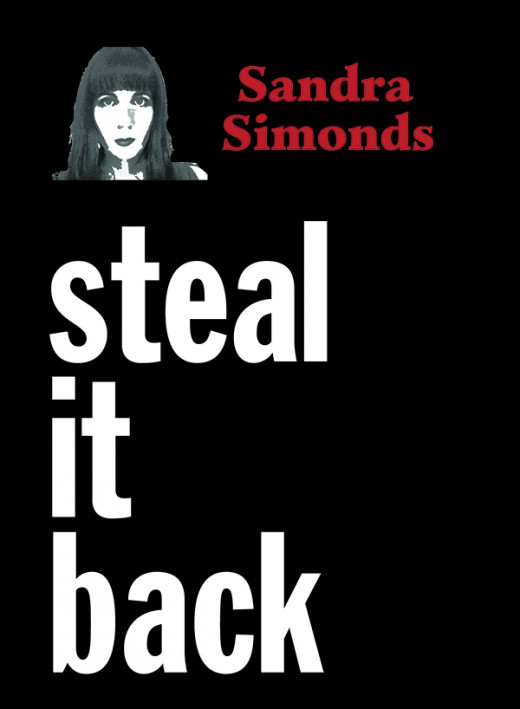

Steal It Back

Claire Eder

SATURNALIA, 96 PP.

The protagonist of Sandra Simonds’s fourth collection of poetry, Steal It Back, is Alice, “a minor poet, a ‘mom’ living / at the beginning of the 21st century.” In the vein of characters like John Berryman’s Henry or Zbigniew Herbert’s Mr. Cogito, Alice is a third-person stand-in, a persona who enters when the “I” decides to take a break. The book’s opening poem, “Alice in America,” shows:

Alice climbing on top of a body

To forget the wars and bullets

There’s Alice with Mutual Fund

Waldorf salads and alcohol

To ward off the inevitable toward

Reading these lines, I thought of Robinson, a persona invented by mid-twentieth-century poet Weldon Kees. In “Aspects of Robinson,” he vacillates between hobnobbing with New York high society (“Robinson at cards at the Algonquin . . . / Robinson in Glen plaid jacket, Scotch-grain shoes, / Black four-in-hand and oxford button-down”) and having a depressive breakdown (“Robinson afraid, drunk, sobbing Robinson / In bed with a Mrs. Morse. Robinson at home; / Decisions: Toynbee or luminol?”). Kees’s Robinson might as well be the Mutual Fund to Simonds’s Alice: a privileged haunter of hotels and consumer of Waldorf salads. Alice might as well be Robinson’s Mrs. Morse. The two characters come from totally different worlds, yet both are lost souls, outsiders, critics of the culture.

Though I love Kees, and Robinson, Alice is the more relatable of the personas. Alice’s world is full of debt, McDonald’s coffee, and not enough childcare. Alice has to deal with misogynist Twitter trolls. Steal It Back tells the story of the Mrs. Morses of the twenty-first century—women trying to make art with few means and with the odds stacked against them. Just as, in an essay appearing on the Best New American Poetry blog, Simonds revises a paragraph from Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet so that it addresses a young unprivileged poet, “Alice in America” functions as a playful yet pointed response to the ubiquity of white male narratives in poetry. The persona of Alice, though closely tied to Simonds herself, expands beyond the personal and invites readers to consider a certain cultural type, the “minor poet,” the “mom,” as a sympathetic underdog as well as an agent of change.

In addition to several stand-alone poems, Steal It Back contains four long sequences that provide ample space for Simonds’s love of accumulated incongruities, juxtaposing the political (“Today Rick Scott fired all the scientists at water management”) with the personal (“I loved my friend but he loved someone else and I was very pregnant / with another man’s baby”), literature with pop culture (“The dream Dante has of the eagle that swoops / his little body from the Middle Ages and places it / in a burnt-out Best Buy”). The resulting world is absurd, drenched in a played-out capitalism. For example, “The Lake Ella Variations” documents the environmental negligence of governments while the speaker reads T-shirt slogans and browses Barnes and Noble. The series “Steal It Back” titles its sections with treasured works of art and architecture, from a Rembrandt painting to the Hall of Mirrors to the Head of Constantine, while the poem interrogates the speaker’s place in the economy: shopping at Sephora, working in academia, navigating debt. Steal It Back will not let us forget our own complicity in building a soulless society. The juxtaposition of priceless works of art with our shoddy, big-box store culture generates an anger that is the book’s main power.

Simonds’s style is direct, her sentences both sharp-edged and fragile in their rawness. The poems are all free verse; they expand through long lines, which voraciously encompass leaps in subject matter, attempting to fulfill the command of the book’s title. Many poems take on a jagged look on the page, with lines jutting out from the left margin at intervals—a form well suited to Steal It Back’s controlled chaos.

My favorite aspect of the book is its sassy humor, often targeting the “po biz” itself: “Gave poetry book I hate five stars on Goodreads; I am such a liar!” I think I actually snorted with laughter reading these lines:

Alice, girl with no belief

system ties knots

into a rope

while listening

to U2 on

her headphones.What? Well, not

everyone in a poem

can have good taste.

The poems in Steal It Back don’t take themselves too seriously, but, at the same time, there is something touchingly tragic about their refusal to own a status as high art. These poems transcend snark through the way they document the challenge of making poetry in a world that refuses to remunerate poets.

In order to write this poem,

I paid daycare $523

for the week. Make sure you premix

the bottles, bring diapers. Make it worth

something, this time.

If the poems don’t take themselves seriously, it’s because culture doesn’t, either. Simonds strives to document the material conditions required to survive as an artist, postulating, “If Plath had had a Malibu beach house, / she wouldn’t have killed herself.” Steal It Back is a haunting litany of all that has been denied to women trying to make something in the world.