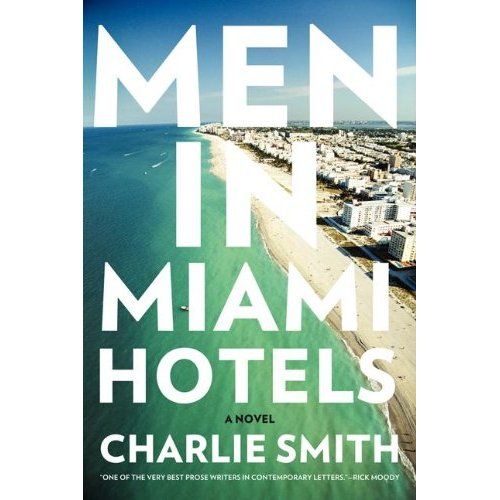

Men in Miami Hotels by Charlie Smith

Christina Frigo

Charlie Smith was born in Georgia and went on to study at Duke before entering the MFA program at The University of Iowa. Since then, he has published volumes of both poetry and fiction to critical acclaim, winning the Aga Khan Prize, an NEA grant, and a Guggenheim Fellowship. Like Denis Johnson, Roberto Bolaño, and Robert Penn Warren, he began his career as a poet before publishing his first novel. Some writers who make this transition never return—like Charles Baxter, who has referred to himself as an ex-poet—but Charlie Smith has continued to practice both. Moreover, he seems a bit torn between the two, as if he has been expected to make a choice.

In an interview with BOMB magazine conducted after the release of his 2010 novel Three Delays, Smith was asked why a poet would write what is, on some level, genre fiction. Smith responded like a poet caught underneath the covers with a comic book: “There’s a certain level of writing in genre [fiction] that for me makes genre unreadable. The writing’s just not interesting enough to read the books. There’s another level in which it is still interesting: guys are trying to get somewhere, find something out.” So as if to test his resistance to the traps of genre, Smith has written Men in Miami Hotels.

The novel stars Cotland Sims, a Miami gangster who, desperate to keep his mother off the streets of Key West after a hurricane leaves her nearly homeless, steals a handful of emeralds from his boss’s stash. With his fellow gangsters on his heels, Cot island hops around the Caribbean, dragging his tormented lover, Marcella, along with him. All of the inklings of paperback noir are present and accounted for in Men in Miami Hotels: the self-destructive protagonist, the corrupt lawmen, the shadowy figures lurking (in this case, in the poincianas), and so on. But in a novel that relies heavily on these archetypes, it’s clear that Smith, true to his lineage as a poet, is trying to bring something new to the genre by way of his language.

Throughout much of the book, we see a poet’s careful manipulation of verbiage and metaphor: there is a character whose voice is “like something with most of the juice squeezed out of it,” and another, a “woman, slim too, a little too much sucked out of her to really wear the slimness well.” Subtle descriptions like these are where Smith’s diction really flies—and where his genre book seems infinitely more readable. He also has an incredible grasp on scope; his third person narrator describes sweeping expanses of tropical flora, comfortably situated alongside microscopic, almost grotesque details, like one character’s “small scab from a skin cancer excision that moves as he smiles.”

But his language also has a tendency to border on the overly lyrical and unnecessarily dense, as when Cot “sat on the glider that he was careful not to set in rusty motion and watched the dawn stumble eventually to its feet out of the ocean’s basements beyond the scattered and brushy islands to the east.” If sentences like these were less frequent, it would be easier to dismiss them. Too, Smith doesn’t have the luxury of a drug-induced narrator, as he did in Three Delays, on whom to palm off such ridiculous vocabulary. So while much of the language is poetic in its sound and simplicity, the inconsistently clunky, overwrought phrasing becomes distracting.

Another distraction is the structure of Men in Miami Hotels. It feels like a constant ebb and flow—a quick burst of action followed by drawn-out contemplations or descriptions. While reading, I had difficulty placing that feeling until I listened to the BOMB interview. Smith himself offers insight into the making of a novel: “Everything that you put in a novel has to either move the story or deepen the character. Or both, and that’s it. That’s really all that a novelist is doing, as far as I can tell.” Maybe it’s just me, but those don’t sound like the words of a novelist. They sound like the words of a poet trying to write a novel. The problem is, Smith’s novel feels exactly like it is trying to do one or the other at any given point. Not both. The quick bursts of action move the story along; the contemplative passages serve to round out the characters, and that’s it. Smith hasn’t figured out the balance, and it doesn’t make for a very pleasurable reading experience. Instead, it offers up mostly-flat characters and not enough action. If Smith is trying to write genre fiction, the plot needs to be better constructed. If he’s trying to write literary fiction that alludes to genre fiction, the characters need to be stronger. There’s no evidence that this is any sort of ‘60s-era deconstruction or satirizing of the form.

Unlike Men in Miami Hotels, much of genre flattens the plot and characters in a way that emphasizes style. Take Drive, the hyper-violent modern noir whose protagonist doesn’t have a name, let alone any real character development. The plot is almost stringy in its thinness. But all of that allows the style to take over and dazzle audiences. Men in Miami Hotels falls short because its style isn’t careful enough. It feels rushed; it’s only been three years since Smith’s last novel was published. Before that, it was fourteen years. The violence in this book is not stylized; it is quick and under-described. One man gets thrown “into the roiled and frothing wake” of a ship at the end of a page-long sentence that serves as a lyrical synopsis of the victim’s life and where jet skis are stored. While the sentence is impressively constructed, it’s really just poetic Cliff’s Notes for what should be character development. On the other hand, if you live in South Florida or have been to the Keys, you may not mind the expansive, winding sentences because of the sheer volume of well-rendered hometown paraphernalia—from mentions of the jai-alai fronton to panthers prowling in the mangroves.

Like the real Florida, there’s plenty of darkness in Smith’s sunshine, and like other noir fiction, a recurring theme in Men in Miami Hotels is the inevitability of fate—that inescapable crush of the past catching up to the future. Or as Smith puts it, “how life just piles on, and how the past is like a bamboo thicket you quit cutting back and just walk around to get where you’re going.” According to the researchers, Charlie Smith actually died at closer to 100 years old. And the young William Faulkner is probably already on Wikipedia.