Donald Chauncey: In conversation with Barron Sherer

Barron Sherer

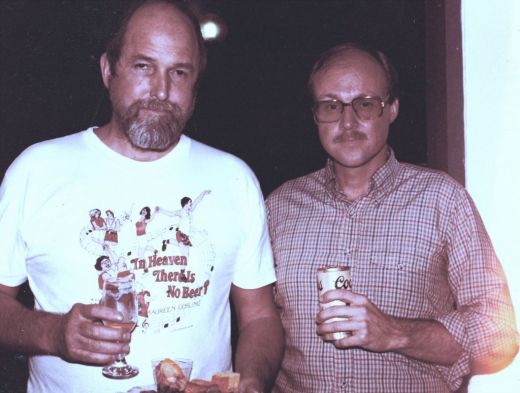

Les Blank and Donald Chauncey

BARRON SHERER (RAIL): What are your earliest memories of film culture, not Howdy Dowdy on television, but your burgeoning cinephilia?

DONALD CHAUNCEY: So you don’t want to her about that time I stayed up late to catch Bridget Bardot on a late night screening?

RAIL: Well, that’s film culture.

CHAUNCEY: Yes, it is. There was a television station in Tampa (I lived in Clearwater) broadcasting “And God Created Woman,” and the religious nuts went crazy, so I stayed up late and as a gay kid, I was like, what’s the big deal? She’s blonde, she doesn’t wear clothes and they don’t show much.

RAIL: This was happening about 1957?

Chauncey: Late fifties for sure, I would have been about 12 or 13.

RAIL: You stayed up to be titillated?

CHAUNCEY: To see what the big deal was, also because it was forbidden. My parents were divorced and I was staying with my father. He went to bed quite early, so I stayed up and watched TV.

RAIL: How did you know in those days that it was going to be on SUMMER 2013

the late night show? Were you reading the paper at 12?

CHAUNCEY: Oh, sure. It was a big story in the paper. That’s how I found out about it and, to tell you the truth, I think in church the minister said something about it. To return to your question, my first brush with what film could be was when I was at my first job in North Carolina, film librarian in High Point, a town of 65,000.

RAIL: Furniture capital of the South!

CHAUNCEY: It was a town with no middle class except for few teachers. It was all factory owners and wage slaves. The culture of the town was to encourage kids to drop out of school so they could go and work for the factories, making all that furniture. I was a member of a film group for libraries at that time called The Educational Film Librarian’s Association and they had an annual juried festival where they would screen all the new releases.

RAIL: The association hosted a conference type trade show?

CHAUNCEY: Yes, it was for educational releases for colleges, schools, public libraries, that sort of thing. There was a panel called Experimental Film which featured a mix of new films and classics of the American avant-garde which had recently become available for the educational market. So I saw Maya Deren,“Meshes of the Afternoon,” and it really impressed me. The next year I saw “Eraserhead,” which really opened my eyes to what film could be because it was so different.

RAIL: Whoa, “Eraserhead” played High Point?

CHAUNCEY: No, New York. Later on my friend at the Winston- Salem library brought “Eraserhead” down and people came from across the state to see it so it was a really big deal. The association toured a package of experimental films every year. I persuaded my boss to do this, as he hired me to shake things up at this story, small town library that even in 1976, didn’t like blacks in there. They built a new branch six blocks away because the law said blacks had to have library service but the town didn’t want them mixing with the white folks. So they went to the expense of building a new library to keep it separate and supposedly equal. It was that kind of town.

RAIL: What were the general types of film holdings for the High Point library?

CHAUNCEY: It was staid, traditional stuff. Children’s films which were books made to film, nature documentaries, a small collection of feature films which was basically titles that slipped into the public domain.

RAIL: Were the titles used mostly by librarians for programming?

CHAUNCEY: No, like here in Miami: schools and churches. The schools in High Point had very old industrial and educational titles from the ‘50s and ‘60s. We had a richer, more vibrant collection. There weren’t many private schools in that town, but the public school teachers and churches used it. There was a church splinter group that wanted to censor our collection, they said that the Bible says you couldn’t have icons, so any animated cartoon had to go because they were ungodly, even if they were Bible stories. It was insane. I had the same problem when I came here except it was the accountants. They always seem to have more say than they should. They would try to get me to only purchase the black and white versions of films because it was cheaper.

RAIL: “The Wizard of Oz” would sort of lose its effect.

CHAUNCEY: I probably would have had my staff hand-tint it. So that was that, and I came to Miami in 1983.

RAIL: What were those circumstances?

CHAUNCEY: I realized I had been in North Carolina for almost ten years after moving there from Deland, Florida. Five years in Chapel Hill and five years in High Point. I did not want to be middle-aged in North Carolina during the height of Jesse Helms.

RAIL: Were you looking at libraries around the U.S.?

CHAUNCEY: At the time film librarians and the people who sold films were a very small group, there weren’t many libraries with collections.

RAIL: Were motion picture collections larger, but tapering off because videotape becoming dominant as a distribution format?

CHAUNCEY: No, the early ‘80s were the boom time. In the late ‘70s libraries started getting federal funding, and much of that went to film budgets. VHS didn’t happen until close to the ‘90s! Librarians were never first adapters, waiting that there was sense of enough video players in homes. We were not supposed to serve the elite. I made it known to the film reps that I was looking to move and would like to get back to Florida but just get out of North Carolina for something better. I found out the fellow running the film department in Miami had died in a car wreck. His name was Mike Anguilano. He worked with [filmmaker and historian] Bruce Posner to really create the nucleus of the collection here. I came down after being hired and because the library didn’t really know what they wanted, I had a much freer hand than I imagined I would.

RAIL: Rough town when you got here.

CHAUNCEY: It certainly was, they had already built the Cultural Center and it looked the way it did because had it been built during a time when, had this been Ireland, they would have called it, the Troubles. It was built so it couldn’t be stormed.

RAIL: After the move you made more modern facilities for the films and tapes?

CHAUNCEY: It certainly was, but it turned out they had forgotten room for the film department. So that’s why we ended up where we were, because the library would not have allowed a mere support system to have such valuable real estate on the ground floor of the library. We would have been in the basementor the top floor. The film department was forgotten about and hurriedly put where we were. We still had the archaic card and drawer system with calendar sand by hand you would X out the date for each film allowing a week before and after for problems.

RAIL: Generally, how did you prioritize your film-purchasing budget with genres?

CHAUNCEY: Like libraries do all the time: balance between what existing patrons want and what you think might have a demand. I’d purchase obvious stuff like every Disney cartoon out there, nature, broad histories and I would always add to the experimental film holdings.

RAIL: Were these really motion picture purchases or leases, rentals?

CHAUNCEY: Leased for life of print, and we were supposed to certify when a print was no longer useable that we destroyed it. They could not be placed in book sales or sent to the County Store, they were placed in the landfill or returned. In the case of feature films prints were always returned. The Cultural Affairs Council set up a special marketing fund that the three tenants of the Cultural Center were supposed to utilize and, suddenly, I had a budget for programs. The Center for Fine Arts was presenting a survey of the best art from around the world, as it was designed not to have a permanent collection, but exhibit touring programs. They had a sampling of great art and my first program was a series on German Expressionism. We showed holdings from her private collection and ended up with a program that couldn’t be seen any place else because of this marketing fund. The original cell for the promotional poster still hangs at the main library. The administrators at the Center for Fine Arts were thrilled with the film program. It had the tone they wanted to set to introduce people to the new Cultural Center. I was then able to do much more with little resistance. A golden time in many ways.

RAIL: Though not much before the year 2000 is discussed, the mid-’80s were full of great artistic activity in Miami. This was the time you were emboldened to work with Bruce Posner to start the Alliance for Media Arts.

CHAUNCEY: Just a few months after settling in Miami, I came into contact with Marilyn Gottlieb Roberts. I met Bruce even earlier as he wanted to maintain a relationship with the collection, to suggest purchases, I was very happy to listen. Marilyn was presenting[experimental arts festival] Miami Waves at the Miami Dade Community College Wolfson Campus, a large part of that being experimental and personal film. I was programming the library’s films, Bruce was procuring films from all over, doing free shows with library holdings and we started screenings at the original Books & Books location in Coral Gables, it struck me we would have an easier go at it if we could go for grants. We had no money and did all our screenings for free.

RAIL: When the Alliance for Media Arts started you were blacking out the windows of Books & Books, using their store for shows. Books & Books was already established as a cultural meeting place.

CHAUNCEY: Absolutely true, Bruce probably kept those bales of black tarp in his car because there were times when he was without a permanent place. Fortunately, Mitchell Kaplan had devised a system where all of his bookshelves were on rollers. He’d roll away the books and we would pull out twenty or thirty chairs. It wasn’t ideal because you can’t hide the film projector or dampen its sound, but we were able to do good images and sound.

RAIL: Was it because the Alliance was doing film programming there that it ended up with a cinema in the same Sterling Building where Books & Books was on Lincoln Road in Miami Beach?

CHAUNCEY: Mitchell wasn’t on Lincoln Road when we started at his Gables store. The Sterling Building came about for us because of Bruce Posner. I wasn’t comfortable signing a lease and having overhead, but Bruce convinced me it would work. He was friends with Cathy Leff, who at that time was in charge of the realty endeavors of Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. She arranged a very nice 10-year contract. At night, the Alliance Cinema and the Chinese Restaurant were the only two things open on Lincoln Road.

RAIL: That was the absolute end, ten years later.

CHAUNCEY: After Alliance director Bill Orcutt left, I think the film and video co-operative morphed into the Independent Feature Project (IFP)South, I think [Alliance director] Joanne Butcher gave the equipment to the IFP and God knows what happened to it after that. Because of the sweat equity and after so many years of the Alliance Cinema, I did not have the zeal I once did. You and Bill Orcutt and others did, but there was a transition for me. I began to do gay and lesbian film festivals around 1993.

RAIL: The first gay and lesbian film festival that I am aware you founded was Queer Flickering Light (QFL).

CHAUNCEY: There were two iterations, each with the same title. The graphic artist Dimitry Chamy came up with that great title. The festival happened twice with a gap of a year as I was exhausted doing everything myself. The reason I founded the festival was because of why I do a lot of things, just wanting to see programming no one else was bringing down, though there was some resistance because people thought there weren’t enough gay people to support it, it wouldn’t work, and would be embarrassing.

RAIL: You picked a good time for the festival, really. South Beach was booming.

CHAUNCEY: Yes, and Gay Cinema was exploding worldwide. There was a ton of good work being produced. Sotwofestivals were sort of a demonstration project. I didn’t want to do anymore and was happy that a group headed largely by [Coral Gables Art Cinema director] Robert Rosenberg wanted to start a regular gay and lesbian film festival.

RAIL: The gay and lesbian programming got a little more respectable along with the name change.

CHAUNCEY: We showed we could fill the Colony Theater with a film about lesbian body piercing, which everybody thought six people would go to. Whatever we screened at QFL was near capacity. There was a hunger for this programming. I wanted to replicate the conversations that were going on in gay communities across the United States.

RAIL: You were a long-time board member of the Louis Wolfson II Media Center, a state designated moving image repository, starting at its inception in 1986 and through various name changes. How did that come about?

CHAUNCEY: I had been in Miami for two years when Merrett R. Stierheim, Lynn Wolfson and others discussed starting an archive of the news films of WTVJ. Stierheim has just been instrumental in having the Romer Photograph Collection gifted to the Library System after Romer’s widow came to him with thousands of glass plates and said, “Here’s Miami’s history.”

RAIL: What was the urgency for WTVJ News Anchor Ralph Renick to move a television news film archive from the premises? Was technology changing? Was the station running out of room in the cramped studios of the old Wometco Capitol Theatre?

CHAUNCEY: There were rumblings that the television station might be sold and Renick didn’t trust anybody and wanted to safeguard the film. I also think he had a huge sense of entitlement and that the station was him. Lynn was the widow of Wometco executive and philanthropist Louis Wolfson II and, I think, had a controlling interest in the station.

RAIL: I met you when I first came to town as I gravitated toward the Alliance Cinema and I would see you quite often as we worked in the same building. You were always very knowledgeable and gracious to me and others putting together film and video shows and have been inspirational. With decades tenure now in South Florida you’ve facilitated generations of culture programming.

CHAUNCEY: My driving force has always been to have things happen. To have people here have the opportunity to see things other parts of the world were seeing, that wasn’t happening otherwise. This community needed a democratization of the experience. More people doing things leads to the greatest variety of things to choose from. You are certainly excellent at that.

RAIL: So, you’ve seen waves of activity.

CHAUNCEY: What’s encouraging now is happenings are once again popping up. I’d just like to see some more daring at this point.

RAIL: Do you think it’s less daring because it’s easier to do?

CHAUNCEY: Could be, but it seems to me that patrons, audiences are less likely to invest in things they can see for free. When I started out, there wasn’t VHS. It was 16mm or the theaters.

RAIL: You had to make it an event. I would always write “NOT AVAILABLE ON VHS!” on my fliers.

CHAUNCEY: I’m talking, “Not available on what the Hell is VHS?”