- Beige Bubble Bodies: New People by Danzy Senna

- The Defiant Infanta: a review of Chantel Acevedo’s The Living Infinite

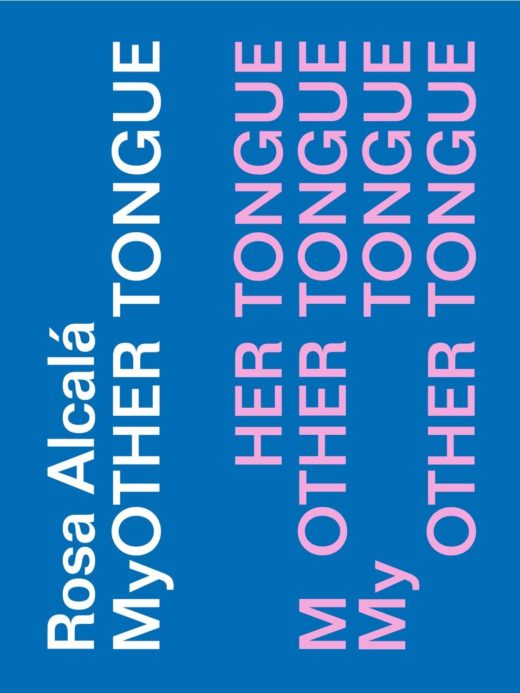

Ghosts of the Archive: A Review of Rosa Alcalá’s MyOther Tongue

Rosa Alcalá’s third collection is haunted: pursued by a flickering language, shadowed by the archive of the body, and insistent on the cycle of mother to daughter to mother to daughter. Located between the finals days and death of her mother, and the birth and early girlhood of her daughter, MyOther Tongue is a persistent and precise examination of the expansiveness of voice and its limitations.

The collection begins as if caught in the throat of the speaker. From the get, “The Story to Be Written” has a cadence of breath, gasping and choking for more. Disruption—repeatedly of language—is cultivated: we are pushed through the poems with ecstatic line breaks and dashed interjections, broken by walls of prose, addressing the mother, the self, the reader, the daughter, language itself. Split into four sections, the collection dedicates its third to “Projection,” a long poem that interacts with Ben Rubin’s media installation “And That’s Just the Way It Is” (2012). In this, I found a key engine of the book: “ghosts / of the archive // multiply ever / steadily.”

“I believe in voice / as I do in ghosts” begins “Voice: An Essay.” The poem shifts deftly from one vignette of ghostly appearance to another, weaving smoothly between anecdotes of haunting. It’s an impressive poem to say the least: the movement between stanzas are smooth and clarifying, the linkage between apparitions of Freud’s patients and attics filled with old lovers (behind whom the speaker closes “the hatch”) is powerful in the unnerving and vividly described nature of the appearances. And, the power of language made into expression is real for this poet: “Voices, like ghosts, / always win. They can / walk through walls / or move furniture.”

Further than just voice, the accumulation of voice: “I believe in poems / as I do haunted houses // …We make sense of noises, /…We ask / questions into / abandoned rooms.” Alcalá is interested in the process of understanding utterance. A poem and its language can only be haunting if it is in pursuit something—or someone. And the archive of these texts is one of inheritance, of matriarchal passing, one that is incomplete and growing.

Beside the realm of language, the collection is after what is contained within the body. In “The Story to Be Written,” Alcalá writes, “We have all in our heads / ancestral myths awaiting, even when / freely / our bodies move / away from them.” Language is not the only way to understanding a past—the body itself is a carrier of information. And, with the emotive exclamation “O, the mercy of the body, trying to out-run history” in “Dear

Stranger,” Alcalá again insists on the archive as inescapable: the body can only make attempts to opt out of ancestral inheritance.

At first read, it seems as if language, written word, can do what the body cannot; it can be more easily wielded through revision and better controlled via printable text. However, that does not seem to be true for Alcalá. She details attempts at controlling language before being thwarted, often by the English language—which poses as lover, but finesses as booty-calling player in “Paramour.” Metaphor has its crown knocked aside in “Voice Activation.” The difficulty of revision is exposed in “Natural Disaster: A Dream” as Alcalá’s desired “idyllic” ending is thwarted by “the instant the wave curls toward the window / and the computer quietly trembles.”

It’s thrilling to see Alcalá put the ars poetica in state of disarray—she has a striking handle on the mechanics of language, with an investment in unsettling emotive shortcuts. Make no mistake: the statement “I’m done with emotion” can only be tongue-in-cheek when pronounced in “Voice Activiation.” The poet is done instead with the trappings of language that obscure emotion. The poem ends: “So I write this poem, which understands me perfectly and never needs the nurse’s station and never worries about unintelligible accents or speaking loudly enough or the trouble with dying, which can be understood as a loss of language. If so, the immigrant, my mother, has been misunderstood for so long; this death is from her last interpreter.”

Vitally, through the exploration of language and the body, Alcalá reaches and reaches again for her mother, questioning: “What likely / cost / incurred / as one / reads /or writes What is / to be read to or by / strangers that isn’t meant / to be sold / or bought? // Mother, / forgive / me for / wanting you to remain familiar / as I flirt with the waiter.” And her attempts are echoed in her interactions with her daughter in “Heritage Speaker”: “What good is it to erect / of absence / a word / like radiator / when we’ve vents / that expel heat / as air. // When I teach my daughter / to speak / and build a woman / out of me / that is not her mother / but some propriety.”

Language alienates, and also pulls these matriarchal sinews tighter. And by the final poem “Ghost Song,” when the daughter touches her mother’s nipple, coos the words of Sappho, the wonder she holds for her mother’s beauty is not just an exaltation of words, but an enactment of repeated history.

Lucia LoTempio is a poet living and studying in Pittsburgh. Her reviews appear in Entropy and Aster(ix), and her poetry appears in The Journal, Linebreak, apt, NightBlock, and more.