Until The Marrow Spills

Justin H. Long

The author, as an eight year old, stands to the far left, alongside his brother Barrett, and his father, who won third place at the 1988 Road America AMA SuperTwins.

My grandfather raced on the beach course at Daytona in the late ’40s and early ’50s. Two miles up the beach sand and two miles back down A1A. He was never seriously injured but bore close witness to a spectator being struck by racers and all parties losing their lives. My father began racing in the early ’60s as pavement tracks took precedent over dirt. As speeds increased so did injuries, and he saw his fair share challenging to be one of America’s best. He learned early that broken bones were merely an inconvenience, rather than a deterrent from doing what he loved. At 12, he ran over his own leg at the now defunct Hialeah Speedway. A month later he cut his cast off with a hacksaw and decided not to return to the doctor.

Through the ’60s and ’70s the trend in race motorcycles was to have a very long gas tank, allowing the rider to tuck in aerodynamically behind fairings to gain more speed. The unfortunate side effect was a lack of rider weight on the front wheel often resulting in a tucked front end and broken collarbone when trying to corner. Anyone who has broken a collar knows the pains associated. Laughing, coughing, sneezing hurt. Dressing yourself and wiping your butt become a huge pain in the ass. 1965 was my father’s first collarbone break. He hit a sand patch while riding a 250 Ducati still equipped with street tires. 1969 saw another at the Dade City track on a different 250 Ducati whose sexy fiberglass gas tank was destroyed in the wreck. 1973 was the third at Charlotte in the junior class.

In 1976, while dicing for third with Gene Romero and lapping the field in the expert race at Pocono, Gene spooked a lapped rider by going inside as my father went outside. The lappy and Dad collided and crashed: another broken collarbone and a furious bodybuilder of a racer trying to fight my father over the incident. The only escape was to climb over a tire wall—exactly as it sounds; a wall made of old tires intended to be softer than hitting a concrete one—and commandeer a spectator’s mini bike. All while sporting another snapped collarbone. 1975 saw the first of three at Daytona in the infamous International Horseshoe turn. Dad was hired as a test rider for Michelin and had modified his Yamaha to accept a larger rear tire. He made half a lap on that cold December morning before the ole tuck and crack happened. In 1988, on a brand new Harris-framed Ducati 750, he did it again. Instead of packing up and going home, Dad decided he could start the Daytona 200 with the broken collarbone. If he could make a lap he could get last place prize money ($750). He made three laps before having a shaky moment exiting the chicane and had to throw in the towel. In 1992, while racing a vintage Triumph 750, the International Horseshoe bit him once again.

1984 Haitian Grand Prix. John Long riding a Rob North, framed Yamaha 350, finished 3rd.

Having him recall each of these took some help for my mother, who was standing by for most of them. There was another in England in 1980—while she was pregnant with me—and hopefully his last in 2005 at Daytona on a Yamaha TZ350, like one he raced and won on 30 years earlier. One collarbone break has deterred many from continuing with racing but foraging through nine takes something special.

My brother and I grew up only half a mile from the motorcycle shop that my grandfather started in 1938. Each day after school from the time I was eight or so we would ride our BMX bikes to the shop and then play with the motorcycles on our own dirt oval racetrack. The track boundaries were decided by a driveway, a concrete wall, a chain link fence, and a city street. The course threaded between the I-beams of a billboard. Many scoffed at its danger but it was ours and no one could go around it faster except for Dad. Learning to go fast and slide a bike meant the occasional wipeout. Being a little kid meant that more often than not when you crashed you got trapped beneath the bike with the exhaust pipe burning your leg. The amount of second and third degree burns we suffered there may be in the hundreds, but neither of us have any scars to prove it.

The scars we do have aren’t pretty and stem from not just motorcycle racing but other yolo activities. My brother’s right hand is quite a specimen. After school one day, on his way to the shop, he collided with an out-of-control cyclist headed the opposite way down the sidewalk. My brother’s only part to make contact was his right pinky. It was torn sideways from the rest of the hand. Thirty stitches were needed.

On a warm summer night in 2006 while leaving our favorite bar PS 14, my brother noticed a hipster couple sitting in his 1969 Fiat 600. Upon approaching them and questioning their reasoning for taking selfies in his car a fight broke out and a pin and screw were added to the mend the pinky carpal. What they call a boxing fracture. On practice day, his Desmomaniacs-sponsored Ducati 1098R superbike developed an oil leak that threw him off the high side at over 100 mph. Landing on his head and shoulder, his collarbone snapped, and sliding across the asphalt wore holes in his gloves to the point that it ground most of the way through a tendon in his right ring finger. He knew he was hurt and like my father before him he climbed over the tire wall to take a spectator’s mini bike to get to a car to drive himself to the hospital.

This wasn’t the first time his hand was hurt racing so he knew he needed to get to a specialist and not where the track ambulance would take him. Unfortunately while visiting his hand specialist, the nurse cleaning the wound bent the finger and snapped the last remaining threads of tendon. His finger is now permanently bent. The first and worst time his hand was hurt racing was at Daytona in 2004 while trying out the AMA 600 supersport class for the first time. During a qualifying lap he suffered a high-side crash in the same International Horseshoe turn that broke my father’s collarbone three times. A high-side occurs when the rear tire of the motorcycle slides while leaned over and then suddenly catches, shooting the rider up to 10 feet in the air to then hit the ground at however fast they were traveling. My brother’s right hand hit the ground first, exploding his middle finger as well as lacerating the index down to the bone.

1974 Transatlantic Match Races, Mallory Park England. John Long (4) riding a Yamaha TZ700, Dave Aldana (5), Barry Sheene (14), Paul Smart (12), Ivon Duhamel (7), Gene Romero (3), Dave Croxford (11).

The doctor in Daytona was a plastic surgeon, not a hand specialist. He suggested amputation because the first joint of the middle finger was missing. Laying on the floor of our vintage motor home, clinching a breast implant stolen from the doctor’s office to cope with the pain of having open bone exposed, my father drove him to Miami in search of a second opinion. The operation required a bone graft taken from his hip to save the finger although he still has no first joint.

While having a short professional racing career myself, the only injuries I suffered were a torn rotator cuff and cracked shoulder blade. My major injuries came from BMX. I decided to attend the University of Central Florida after high school. Orlando had a better BMX scene than Miami and the school’s engineering program wasn’t too bad either. Unfortunately I enjoyed the BMX more than the engineering, and my grades suffered.

A week before finals freshman year and on the brink of flunking out, I was riding with some friends on campus. I looped out upon landing a barspin down a small set of stairs. My left foot twisted completely around backwards as I fell to the floor. It sounded like snapping a branch over your knee; I knew it was broken. At 18, having never broken anything besides a finger or toe, that snapping sound really scared me. I screamed bloody murder as my friends tried to calm me down by convincing me that it wasn’t broken. They dusted me off and got me back on my bike to scoot my way through campus to the infirmary which amazingly had an x-ray machine. A plate and eight screws were required to hold together that spirally fractured fibula.

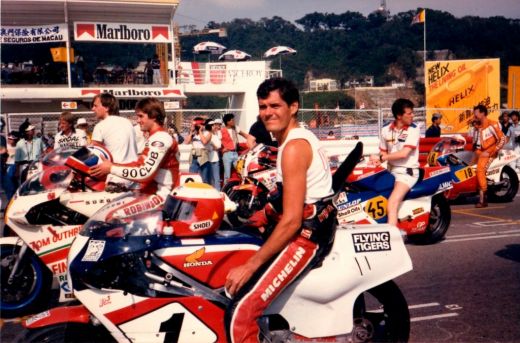

1985 Macau Grand Prix starting grid. John Long riding Mac Archer’s Honda RS500.

***

A few years later and after graduating as an artist rather than an engineer it happened again. This time while riding at the Miami’s now-defunct Control Skatepark as we did each day. The last hour of daylight was the best for the outdoor mini ramp. Not too hot, not too long of a session, filled with good times. My brother and two younger riders were on deck. I was warming up when my back peg slipped off an ice-pick stall. While sliding down the ramp, the toe of my right foot caught and twisted my leg beneath me causing the dreadful snap but this time twice.

I stay calm this time and roll to my back, speaking in a normal tone to my brother. “Go get the car, I broke my leg.” He replies “yeah right.” I lift my jeans to show a new bend between my knee and ankle. His smile drops and the two younger riders get pale. My brother pulls the car up to the outdoor ramp as I slide backwards on my butt and pull myself into the passenger seat. The throbbing sets in as we drive to the hospital.

My calm demeanor fools the nurses when we arrive to the point that they are apprehensive to give me a wheelchair. The doctor asks when I last broke my leg. “My left one was five years ago.” “No, your right one. See here,” he points to the x-ray. “It was broken before.” So one of my other numerous injuries had broken the right fibula before and I didn’t know it. This time it was a tib-fib. Two plates and 12 screws later it’s back together again.

***

Between the Long boys there have been many surgeries, stitches, and stories for a lifetime. Each doing something we love and paying for it with a little set-back. My father at 63 still races, my brother at 30 does as well. At 33, I still ride BMX and motorcycles and each day the premature arthritis in my legs reminds me that I am paying for it. Still, these breaks have changed our lives for the better.

In 1977, after a crash at Mosport in Canada, my father and mother were riding in an ambulance to the hospital. Another motorcycle had run over his arm. Both bones were broken between the wrist and elbow. As the throbbing set in and worries of his marrow spilling out of the fractures began to race through his mind, he turned to my mother and said, “Hey, I think we should get married.”