Florida Prize in Contemporary Art Exhibition

GREGG PERKINS

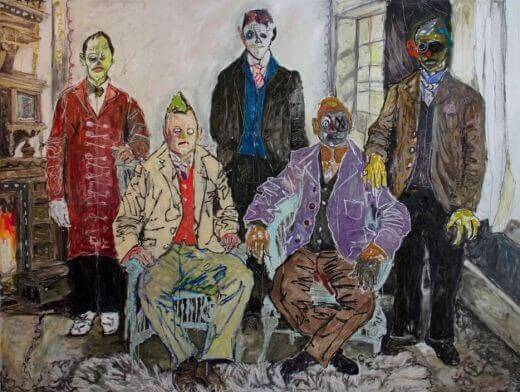

Farley Aguilar, Patriarchy, 2015. Oil on linen, 175.3 x 236.2 cm. Collection of Beth Rudin DeWoody. © 2015 Farley Aguilar. Image courtesy the artist and Spinello Projects, Miami

June 12–September 6, 2015

What’s most evident in the selection of Florida artists on view in the Florida Prize in Contemporary Art Exhibition at the Orlando Museum of Art is that each is simultaneously aware of his or her place within an art historical framework and that, culturally, we are squarely in the post-historical age of eternal appropriation, recombination, and mash-up. The general sense of this cultural remix unfolds more or less brilliantly throughout the expansive three-gallery show.

This year’s prizewinner is Farley Aguilar, whose paintings evoke the works of James Ensor as much as Jean-Michel Basquiat, but with a decidedly monster movie–like tone. The aggressively painted canvases and textual elements take their source from found photographs of American life, and the figures inhabit these scenes with a palpable sense of dread. This foreboding derives from his- torical instances of social injustices found within the original images. For example, in Patriarchy (2015), a zombielike figure clad in a butler’s uniform has the word “servant” scrawled across his sickly green forehead. Farley’s counterpart in the show is Michael Covello’s installation of abstract works, including The Forest Ravenous (2015), which ranges across styles from process painting to minimalism. Two black monochromatic paintings are fixed in front of a matrix of neon webs of paint applied directly to the wall, as if icons of twentieth-century abstraction hovering uneasily above a chaotic jungle of biomorphic forms.

Jennifer Kaczmarek’s ongoing photography project Love for Alyssa documents Alyssa Hagstrom struggling with the crippling disease Arthrogryposis. These portraits depict Hagstrom intimately, in times of suffering but also with a cherubic and, at times, comical levity. The Spiderman Challenge (2011), for example, depicts the slight Hagstrom in a Spiderman outfit blocking the way of another child’s bike; unclear if this is an arrest or not, we’re left seeing subtle nuances within the relationship between photographer and her beloved subject.

Cesar Corjejo’s architectural installation Puno MoCA Pavilion at the Orlando Museum of Art (2015) is a stand-alone museum within the gallery and points to a project in his native Peru where, in renovating rooms for citizens of Puno, they exchange the spaces to become galleries, thereby fusing architecture, renovation, and community engagement through his poignant lens of situational art making. Working along political lines, Rob Durane approaches an unseemly political narrative in Lost #2 (2015); a complex video projection of news clips about US drone strikes is reflected on a sculptural elevation map of Pakistan in relief, including names of each individual killed in these attacks. The obscured image produced comments on how information about these strikes is made public.

In a gallery space to themselves, the works of Bhakti Baxter and Nicolas Lobo compliment one another through their varied employment of conceptual and minimal strategies to differing effects. Baxter presents a crisp and playful set of works that obliquely nod to Marcel Duchamp through a trippy Rotorelief-like wall painting Circle Spiral for OMA (Relax your Gaze) (2015). On a darker trajectory, Lobo’s Napalm Stone (Nexcite Version No. 1) (2014) presents biomorphic Dada-like forms comprised of a caustic set of materials. The base material is play-dough that has been carved with petroleum, a constituent element within Napalm, and colored with the neon-blue Swedish power drink Nexcite. Both visceral and toxic, these forms, placed on terrazzo bases, feel like post-historical ghosts of modernist sculptures.

Also drawing on minimalist materials and post-minimalist artistic strategies, Alex Trimino’s Totem Feast (2015) is a bright installation comprised of vertically aligned sculptures incorporating neon and florescent lights, fabric, tree stumps, and a score of other materials. But here the industrial materials such as neon and florescent are playfully transformed; the overall effect is that of being in a tweaked electrical forest, knit together with the familiarity everyday materials.

Wanda Raimundi-Ortiz’s multimedia work embodies a bold, in-your-face, comical, but ultimately dead-serious look at American otherness as a Latina. Wall drawings such as This is My Crown (You May Not Touch It) (2015) embody this ethos squarely. Similarly, in the comical Ask Chuleta videos, Raimundi-Oritz’s emphati- cally elucidates aspects the contemporary art world through the character Chuelta. In #17 The Hustle (2012), Raimundi-Ortiz, donning a Warhol wig, both explains and calls the the art world out on its equivocating relationship to the art market.

More strictly a performance work, Antonia Wright’s trio of video projects on view survey her experimentations in which she places herself in vulnerable or downright hazardous scenarios to acute aesthetic effect. In Suddenly We Jumped (1) (2014), we see the artist’s nude figure slowly rising in out of the dark, abruptly shattering through a sheet of plate glass as she ascends toward the camera, then receding back into the void below. Titled after a line from Futurism’s Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Suddenly We Jumped sends up the Futurist ban on nudity while also asserting both the elegant and fierce power of a female figure in motion.