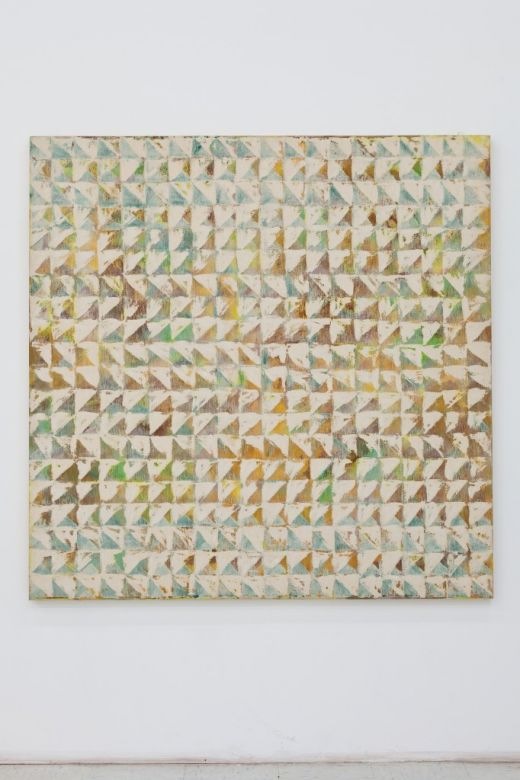

One of Lynne Golob Gelfman’s paintings from her Trued Surface

-JEAN BAUDRILLARD Simulacres et Simulation (1981)

…The simulacrum is not a degraded copy. It harbors a positive power which denies the original and the copy, the model and the reproduction…There is no longer any privileged point of view…modernity is defined by the power of the simulacrum.

-GILLES DELEUZE “Plato and the Simulacrum” (1990)

In what follows, I will do exactly what some in the artistic community of Miami have warned me is untenable: To speak with presumed authority about a cultural setting to which I have been exposed only briefly. Perhaps these admonitions are apposite. After all, to speak of art is too much a privilege to leave to either mediocrity or imprecision. And yet, to be entirely original is difficult; to reveal hidden profundities more difficult still. To aspire to be both original and profound is, for a writer, a perilous business. It is just as perilous to make grand statements about the art scene of Miami, a city that, like that ever-shifting mirage known as the “fata morgana,” not only acknowledges the factors that make its haecceity difficult to articulate, but even revels in forswearing its own singularity. Moreover, the presumption of issuing proclamations about the “Miami art scene” becomes more brazen still when pronounced by a traveler who possesses all the ethos that 48 hours can confer. And that variety of ethos is most compelling when wielded by a child or a 19th-century German Romanticist. I am neither.

The Miami art scene(1) is charged with a palpable tension. At stake is nothing less than the defining qualities of the developing aesthetic gestalt. This tension can best be conceptualized as a battle of different versions of the “simulacrum,” a term that is as old as Plato and has been contested nearly as long. Though a simulacrum can be described as, roughly, an insubstantial semblance, there is also a possibility of dissimulation that lingers about it, for it replicates a particle of reality not as it is but as it might be. Far from a matter of sterile academic debate, how the Miami art community defines itself in relation to the idea of the simulacrum (and perhaps even as a simulacrum itself) will help define an identity still inchoate.

The notion that the “simulacrum” is the radix malorum, the “root of all evils,” is not universally held, as the warring citations of Baudrillard and Deleuze included above suggest. The Baudrillard camp, taking a cue from Plato’s view of the arts, condemns the simulacrum as a form of representation that does not replicate existing reality but offers a mere perversion of it, a monstrous distortion. For the Baudrillardist, the simulacrum contains no bid on reality, a defect that Baudrillard applies to contemporary society, its emptiness an allegory for the perversity of a modern world that languishes in its own self-reflexivity. Taken as a simulacrum in those terms, Miami appears a land of lost referents, made by desires not its own, unmade on a whim—its aesthetic nothing but empty, careless, derivative dreams of an energetic yet callow art scene.

But there is a second possibility. As Deleuze has argued, the simulacrum is not abomination of Platonic reality; it is instead an offer of boundlessness mercifully unfettered by the constraints of the Real. It is the great gift of a modern age unfettered by petty considerations of actual reality. In Deleuzian terms, Miami’s manic referentiality, its identities and histories are folded into an entity altogether different, wonderful; its art scene is a massive, burgeoning collage so vibrant that reality could never manage to frame it.

Installation view of Alan Gutierrez’s Nobody Knows Me Better Than You at Locust Projects.

The two versions of the simulacrum are embodied by two Miami landmarks: the Wynwood Walls and the Pérez Art Museum Miami. The Walls (located in the midst of a gallery district that was innovative a decade ago and has, in recent years lapsed into complacency), were created in 2009 as part of a gentrification project by Tony Goldman. It is practically a bastion of self-irony trimmed with an iniquitous self-awareness, a perfect case for Baudrillard’s pejorative simulacrum. As they enter the Walls, visitors are confronted with an urbanized Disneyland as they promenade along a path girded by a tightly trimmed lawn. At one side merry patrons of the Wall’s restaurant are seated (which, incidentally, creates the impression of a café scene not unlike a tragic epigone of Les Deux Magots). The “walls” themselves provide the canvas for the work of noted graffiti artists. The box-like structures of former warehouses are covered with street art, which for radical expressions of rebellion are mostly of a tepid turn aesthetically. Wynwood Walls manages to make a neighborhood’s past socio-economic profile into a sterile, aestheticized mythology of ghetto-style revolt against authority. Paradoxically, the Walls reassure us that civility has arrived in the area. The Wynwood Walls may be several things but it is, at its core, a simulacrum of the Baudrillard variety. Its form derives only from the caricature of what we imagine it has replaced.

A positive version of the simulacrum as Deleuze envisioned it exists in the shape of the Pérez Art Museum Miami, which opened in December 2013. The museum is nestled on Museum Park in downtown Miami, and flirts with Biscayne Bay; a flotilla of cruise and cargo ships drift in the background. If Wynwood is the hyperbolic manifestation of an identity valued only in the luxury of its rejection, Pérez manifests no overt sympathies with the simplicity of a single identity. Nonetheless, every decision by the architects who constructed the Museum, Herzog & de Meuron, has been inflected by a very basic reality: that of Miami as a physical entity, a site partially shaped by the realities of light, shade, and temperature—one vulnerable to the constant possibility of natural disaster. Outside, columnar hanging gardens designed by Patrick Blanc slyly inherit those architectural ensigns of political and religious authority and simultaneously allude to those famed Hanging Gardens of Babylon (which, incidentally, might have existed only in the Orientalizing imaginations of 4th-century CE Roman geographers). From its teak doors to the storm-proofed, UV-resistant walls of glass that overlook the second floor, the museum has taken both the vocabulary of the Traditional Museum layout (complete with a grand staircase), and the particularity of Miami as a geographical reality and created simulacrum of the Deleuzian order. PAMM’s architecture creates a vision of a Miami forever in process, a place the authenticity of which is metaphorized by the Museum’s unfinished oak floors, never reaching completion, only gaining complexity.

While the art scene as a whole might be conceptualized by two versions of the simulacrum, this duality is expressed by two opposing themes within individual works: palimpsest and surface. To take the second first, galleries from the Design District to South Beach bespeak a persistent fascination with surfaces, both literal and metaphorical—with seeming, simulating, dissimulating. At the Bas Fisher Invitational, the print twin of a CD by Paris Hilton presses the heiress, a doyenne of superficiality and baseless fame, into the literal two-dimensional reality as an editioned work. Although this work, by New York-based Cory Arcangel, is neither new nor a product of a Miami studio, its migration here is telling. Supernatural: Religious, Theological and Spiritual Leaders, a recent exhibition of paintings by Bryan Drury at Dean Projects in Miami Beach is a prime example of an aesthetic that not only embraces the mimetic but glories in it across seven portraits of significant religious leaders. Drury’s portraits are unmercifully wedded to simulating reality, of capturing the details that by necessity or vanity go untold; every wrinkle at the corner of Kabbalist Karen Berg’s eye, each hair of Rabbi Saul Kassin’s voluminous beard seem to be accounted for. The Supernatural series is a curious one, for it offers the gift of humanity, of hyperreality, but tempers it with the obvious fact that it is merely a simulation.

Meanwhile at Locust Projects, beyond the ‘eternalized’ roses that punctuate Virginia Poundstone’s evocative BOG-MIA exhibition, is Alan Gutierrez’s suggestively titled Nobody Knows Me Better Than You. The exhibition consists of a series of canvases branded with the artist’s initials. Though the conceit would be well worn in New York, for Miami, the drama that it enables Gutierrez to bring forth is apposite. His works stage the ridiculousness of the moment where referents are so alienated from the referees, in this case the artist himself, that they only appear, fleetingly, to reference intimacy (as does the inviting title, full of platonic or even erotic connotations). In evoking the most personal register and juxtaposing it with one of the most insincerely impersonal ones, Gutierrez manages to recreate himself as a simulacrum: a version of, simultaneously, the symbolic transformation of art to commodity, a referent with meaning only to itself.

Moving art around Wynwood Walls.

An art scene consisting only of slick surfaces and simulations: to assume this describes the whole is misapprehension. There is another abiding theme which is, though less readily apparent, perhaps the most eloquent response to both the fiction of the surface and the threat of the Baudrillardian version of the simulacrum: the palimpsest. In some exhibitions, there is an urge to create space defined by impositions or incompletion, excess or palpable absence. The former is vividly expressed in Beatriz Monteavaro at Emerson Dorsch in Ouroboros where, as part of the exhibition of Monteavaro—who is both an artist and a musician—flyers for performances by underground rock bands keep time with pages torn from Ecclesiastes.

It is Lynne Golob Gelfman’s Trued Surface at Dimensions Variable that best expresses the figure of the palimpsest—and makes a case for the power of the positive version of the simulacrum—most eloquently. The exhibition is vaguely palimpsestic as the modest scale of the first works featured in the exhibition (the tallest no greater than nine inches) made in 1980 are superseded by the gleaming “thru gold 2” (1978) that both predates the smaller works and augurs the remainder of paintings in the exhibition (all composed between 2013-2014), both in their larger scale and their more overt geometric abstraction, at turns meditative and restless. What makes Gelfman’s work palimpsestic lies not merely in the allusion to an emergence that is suspended in an insinuating kind of overpainting, as in “tri/brown/blue” (1980) nor even in the layers of graph paper that seem froward, like a rebellious background declaring its emergence that appears in several compositions. No, it is not merely some mechanical element in Gelfman’s works but the mere play of colors and uncommitted shapes that creates a dynamic, where rebellions of pigment that rise and retreat are suggested, implying depth not by a trick of perspective but by notable irregularity in a sea of regularity. Gelfman’s works are commanded by limits yet suggest nothing less than outstripping them. As a result, the compositions reflect a sense of emergence, the feeling that something is imminent; something is developing…something beyond our view.

One of the cities Italo Calvino invents in Le Città Invisibili, is Valdrada, a city that exists in double-ness, in both itself and its own reflection. Of the relationship between the two Calvino muses:

At times the mirror increases a thing’s value, at times it negates it. Not everything that seems valuable above the mirror maintains its force when mirrored…The two Valdradas live for each other, their eyes are locked; but there is not affection between them… (54, translation mine)

Calvino’s double Valdradas are like a simple allegory for the Miami art scene. The concept of the two versions of the simulacrum is not an antagonistic one. Ultimately, that duality is not an undecided battle; it constitutes an identity. True, occasionally there will be casualties from this indecision such as exhibitions featuring artworks that are pallid, derivative, obvious—even embarrassingly bad. But the doubleness of the enterprise makes these galleries pulse with a vitality, a perpetual risk of being pressed into over-determined versions of itself, into Baudrillard’s simulacrum, and the Deleuzian triumph of creating something better.

1 Before continuing, the definition of what is intended by “Miami art scene” is necessary. For the purposes of this essay, the phrase does not mean art produced by Miami artists or, necessarily, in Miami. Rather, it means the art that is not just being created, but which is being exhibited in the city, what is cultivated, what is of interest, what is being consumed. The artists might as well be Canadian as Cuban.