One Hundred Years of Weirditude: On the Streets and in the Archives

Tom Austin & Cristina Favretto

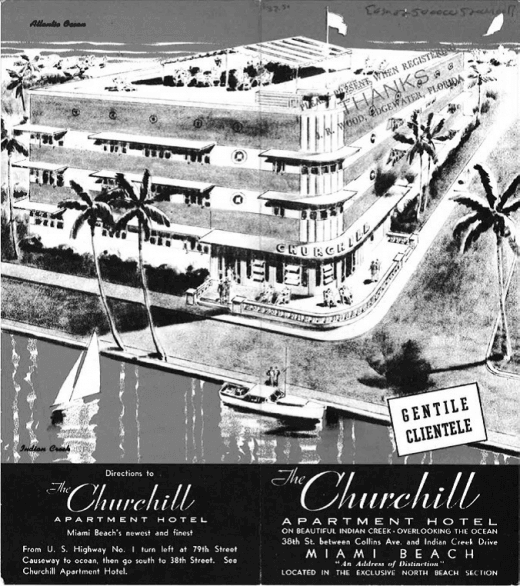

Photo of the Miami good life from the Florida Promotional Materials Collection. Department of Special Collections, University of Miami Libraries

My family moved to Miami in 1970. A day trip to the Fontainebleau Hotel—the ballyhooed home of Goldfinger, Elvis, Frank Sinatra, and Meyer Lansky—was our first family outing. By then, the Fontainebleau was all ashes and myth, with a palpable shroud of defeat and corruption clinging to it: the real estate equivalent of one of those withered mob bosses who dodge jail by claiming all manner of pressing illnesses. Today, in synch with the era of Art Basel Miami Beach, the Fontainebleau has the obligatory contemporary art quotient, with works on view by Ai Weiwei and Tracey Emin. NADA Miami Beach is leaving behind the goofy kitsch of the Deauville Beach Resort and will set up camp at the Fontainebleau in December.

Nostalgia is a kind of violence, and everyone believes his own youth was the best possible era to be young, but the 1970s, ‘80s, and early ‘90s on Miami Beach was definitely a choice cultural moment. During the 1972 Republican National Convention on Miami Beach, the Fontainebleau was the Republican base camp, and high school kids from all over Dade County protested outside the hotel. That same year, during the Democratic National Convention, all the forces of protest, from the Yippies to the Black Panthers, set up a kind of floating Woodstock in Flamingo Park. On top of all that counter-culture cool, the Miami youth quake scene in that era revolved around the former pier on lower South Beach, full of feral surfer kids. Every Art Deco hotel had a gaggle of old retirees rocking on the front porch, smiling beatifically at the nice young people who would eventually price them out of their homes.

In the 1980s, South Beach was early Wynwood in tone, a mix of edgy bars and artists: at the Cardozo, one of the few places to drink, Christo hung out during the preparations for his and Jeanne-Claude’s Surrounded Islands in 1983. At night, we’d all go dancing at Beirut, a punk/New Wave club, or Club Z (now Mansion). Miami Vice had a party at Club Z, and Don Johnson—who would wind up on the cover of Interview magazine’s Miami issue—was pretty much ignored; to even approach a celebrity was considered terminally uncool, an exercise in debasement.

In 1986, Micky Wolfson opened the Wolfsonian Museum amid the squalor of Washington Avenue. Squalor was something of a local growth industry. Bruce Weber and Helmut Newton came to South Beach for the atmospheric squalor that made for good fashion backdrops and documentary photography alike—Stephen Shore, Rosalind Solomon, Mary Ellen Mark, William Eggleston, Gary Monroe, and Mitch Epstein all shot there.

The pre-chain store era of Lincoln Road was endlessly diverting. Long before the opening of the Frank Gehry–designed New World Center and the acclaimed Wallcasts, the symphony was based at the Lincoln Theatre. In the evenings on Lincoln Road, strollers watched concerts broadcast live on a television monitor outside. Across Lincoln Road, the Bone Boyz—a duo who lived in the penthouse of the Van Dyke building, where pioneer developer Carl Fisher once had a sales office for his real estate empire—would stage free street theater, dangling a mannequin in S&M attire off the roof like a fishing lure.

Miami City Ballet rehearsed in a former Lincoln Road department store with huge glass windows. When ballet paled, locals would wander into the art studio of Carlos Betancourt or take in the Art Center/South Florida, which was just sold for a pile of money and closed down with the final group exhibition Thirty Years on the Road, drawn from three decades of resident artists like Whitney Biennial veteran Luis Gispert. In the early 1990s, Mitchell Kaplan opened an outpost of Books & Books and Jason Rubell opened a gallery. The gallery proved to be too far ahead of its time, and Vanilla Ice, a Star Island resident and Madonna consort, took over the space for a skateboard/BMX/regular guy shop.

Art was a casual, everyday thing. In 1979, Roy Lichtenstein unveiled the sculpture Mermaid outside what is now the Fillmore Miami Beach at the Jackie Gleason Theater, resulting in one of the earliest public art projects in Miami. Félix González-Torres and Larry Rivers were around in the early days, and Roberto Juarez adopted a street character—an old Miami Beach va-voom type who’d morphed into John Waters territory—as his muse. Antoni Miralda and Montse Guillen, early pioneers in using food as a medium, had fantastic opening parties at their Espanola Way studios. Fernando Garcia, Jack Pierson, and Carlos Alfonso would turn up at art events. Nam June Paik lived and worked in a nutty building on Ocean Drive. Kenny Scharf, Jose Parla, Tomata du Plenty, and Craig Coleman (aka Varla) created work for nightclubs. Kevin Arrow, who did nightclub installations in that era, published Tropical Depression SOBE 96, a zine about the artistry involved in the early South Beach club world. Currently, Arrow is working on an exhibition of Craig Coleman’s art. Old South Beach lives on.

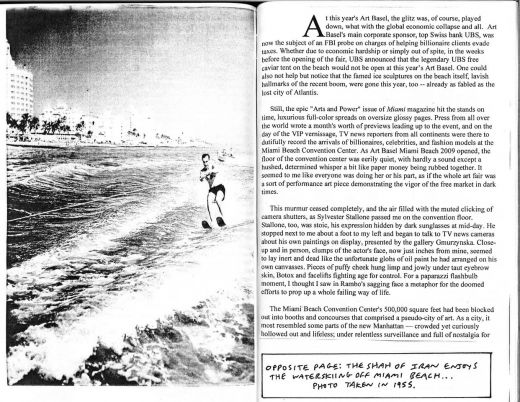

Miami fun-in-the-sun takedown courtesy of Erick Lyle (Iggy Scam) in the “Greetings from Miami Florida” issue (2009)

Since Art Basel launched in 2002, South Beach has managed the neat trick of being simultaneously more sophisticated and more dumbed-down. South Beach is a breeding ground for EDM club music and hip hop, with Tiesto, Pitbull, Lil Wayne, and Pharrell Williams rooting its brand in the world’s brain pan, far beyond what Gianni Versace and countless other gay pioneers of South Beach could have envisioned. South Beach’s marketing punch can sell the SoBe Clutch by Louis Vuitton, and just as easily, fuel the hawking of SoBe Sodas, the South Beach Diet, South Beach Labsis skincare products, and South Beach Smoke electronic cigarettes. Lego Land even has a Lego block recreation of Ocean Drive, which pretty well sums up South Beach’s stature in the world. (Art Deco savior Barbara Capitman, ironically enough, had originally envisioned a restored South Beach as a kind of living theme park with guides in 1930s ensembles.)

Miami Beach officialdom, which once fought against historic designation for the Art Deco District and now considers Romero Britto a kind of goodwill art ambassador, has never really understood the true power of South Beach. Spectacles mean nothing. A great city, like a great life, stands revealed in an accidental accumulation of small tender moments, and as the cliché goes, the best things in life are free. On the walk home from the Hard Rock Rising centennial festivities, surrounded by the usual throng of frat thugs spilling out of bars, I stumbled on an inkling of grace being conducted on the front porch of an Art Deco hotel: an evangelical minister was leading a service, smack dab in the middle of Sodom and Gomorrah. The congregants were oblivious to history and their surroundings, and for a few minutes, I was young again on South Beach, struck with wonder by the weirdest place on earth.

TOM AUSTIN is currently at work on Beyond Basel: A Cultural History of South Beach, and is a finalist for the 2015 South Florida Knight Arts Challenge.

I am not a Miami native. When I moved here six years ago, I will confess that for at least two years, I stepped very gingerly into the Miami maelstrom, and that I did not allow myself to become immersed in the culture, color, and cacophony of the Magic City. In fact, I was utterly blind to the magic, gritting my teeth and quietly (and sometimes less than quietly) cursing the traffic, the bad service in restaurants, the lack of farmer’s markets to compare with those of Santa Monica, the bandage dresses, the bad service (yes, I’ll repeat it). Los Angeles’ history seemed less shallow, and my former city of Durham seemed more sophisticated. Miami was the rebound boyfriend one can pick apart and poke with sticks. And then, as in a cheesy romance movie from the 1950s, I suddenly found myself gobsmacked in love with the rebound boyfriend, adoring his (well, really her, because this is a female city) every idiosyncrasy, marveling at the indigo-green-turquoise crystalline seas, the coy little black lizards, the elegant monstera deliciosas, the whirring-booming-shouting skyline, and most of all, the kooky, kooky, super-kooky beauty of its diverse, nutty, rude, loving, cheek-kissing inhabitants.

This is not to say I give the rebound boyfriend a pass. She needs some work, clearly, but the solid foundation is there, even though it’s built on gossamer sands and the wheedling wings of mosquitos.

And aren’t I lucky that I have the opportunity to go to my job every single day and work—together with my fabulous, hardworking, and creative colleagues—on preserving not only the history of South Florida in all its many incarnations and eras, but also safeguarding history in the making.

A word about archives and archivists: we are stealthy. We are watching you. If you’re doing something interesting, we will approach you and make you Give. Us. Your. Stuff. And you should be open to our requests, and understand that in return for your scrapbooks, photos, correspondence, and diaries, we will ensure that your place in history is firmly marked, locked, and loaded for bear. We won’t take everything, we will be selective, and we will look askance if you ask us for money because it costs us a great deal to clean it, arrange and catalog it, house it in nice acid-free boxes, and place it on temperature-and humidity-controlled shelves. In return, one, ten, or one hundred years from now, your papers will be there: clean, described, and ready for generations of researchers to pick apart, investigate, study. You will be, in the nicest possible way, immortal.

The Special Collections department at the University of Miami houses not only a fabulous collection of rare books and manuscripts, but also the archives of families such as the Monroes of Coconut Grove, the Merricks of Coral Gables, and the Mathesons of, well, Matheson Hammock. We also have over fifteen hundred boxes of materials documenting the fabulous history of Pan American World Airways, Inc. (including a gorgeous collection of flight attendant uniforms and menus from the years when they not only had menus, but also served caviar), and over five hundred collections, large and small, on all aspects of local and Caribbean culture.

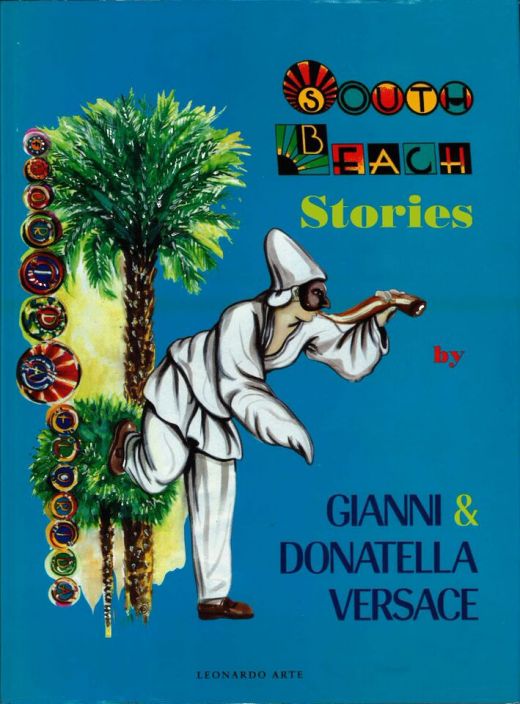

Miami Beach, in all its glory, is represented in a collection of historic postcards, some of them with the obligatory “I’m here and you’re not, ha ha!” sentiment and many with scenes of bodacious pin-up style beauties lying in the sun in 1950s obliviousness of the damage being wreaked upon their fair complexions by UV rays. We also have a fascinating collection of hotel brochures, many of them sadly attesting to the city’s lack of discernment when it came to tearing down jewel-like structures. Some of them still here, preserved by the insight and general swellness of a kickass preservation community and hoteliers and developers with insight and soul. And then there are the Great Unusual Hiccups, i.e., material that can’t quite be defined, like one example that might be called a coffee table book—an exegises on handsome lookalike boys wandering about South Beach with ornate shirtfronts agape and shining hair swinging in the breeze. It’s called South Beach Stories, and it purports to be by Gianni and Donatella Versace but it…well, you’ll just have to come and see for yourself.

Cover of the unintentionally hilarious Gianni and Donatella-penned (actually written by Marco Parma) South Beach Stories (Milan: Leonardo Arte, 1993). Department of Special Collections, University of Miami Libraries

All these types of materials are to be expected in any good archive, but here’s where we truly live up to our “special” moniker: we are building a very amazing Miami Counterculture Collection. It contains over six thousand zines (ephemeral photocopied publications about music, art, politics, sexuality, love, fashion, anything), a good number of which are about Miami or Florida. Some of these zines, like Erik Lyle’s (aka Iggy Scam’s) Scam document his sharp attacks on real estate–fueled greed and the slow theft of public waterfront spaces on South Beach. Lyle’s collection includes instructions on how to squat in half-finished buildings, hand-drawn maps of his neighborhood, and fliers for punk shows at South Beach’s Cameo Club. It also contains the personal and organizational archives of a variety of Miami Beach writers, artists, and creative ne’er-do-wells.

And if we are not ever-vigilant for the creeping insidiousness of mainstream media-fueled worship of the should-not-be-worshipped crowd (e.g., the Kardashians and Kardashian-adjacent), we Miamians and Miami Beachers will be seen in just the vapid and anti-intellectual, uncool light against which we rail. And so: instead of only documenting the famous and those who can hire publicists for themselves, it is important to represent the flies in the ointment, the outliers, and the avant-gardists. These would include the great Howard Davis, who with a merry group of visionaries hosted the roving Artifacts party, and whose archive now lives on here.

There is more. Much more. There are photos of devastating damage from the Great Hurricane of 1926, cookbooks from restaurants that no longer exist, and there are the history-in-the-making papers of the O, Miami fellowship of idealistic poetry purveyors. And it’s all there to explore, to investigate, to build upon. We’re all making history, day after day, and because we love this crazy, beautiful, corrupt, happy, sad stretch of sand, we want the world to know about it.

CRISTINA FAVRETTO is Head of Special Collections, University of Miami Libraries.